Rebuilding India’s state capacity is an urgent task, which several scholars have been pointing out well before the Covid-19 pandemic struck. But the problem is, India cannot take a time out from the international system to fix its domestic problems. The unfortunate situation is that, as urgent as the task of building India’s capacity is, New Delhi will have to figure a way out to do both simultaneously: deal with the international condition and rebuild itself domestically.

Rebuilding state capacity is necessary not just for domestic purposes. The weakness of India’s state capacity dilutes Indian power externally, and potentially makes it more vulnerable. This weakness does have a foreign policy cost. It is just that India will have to work hard to hold the line externally while undertaking the difficult internal task.

Also read: India’s hope is ebbing. It needs a leader who focuses on health, not victory

Raise state capacity, not foreign policy cost

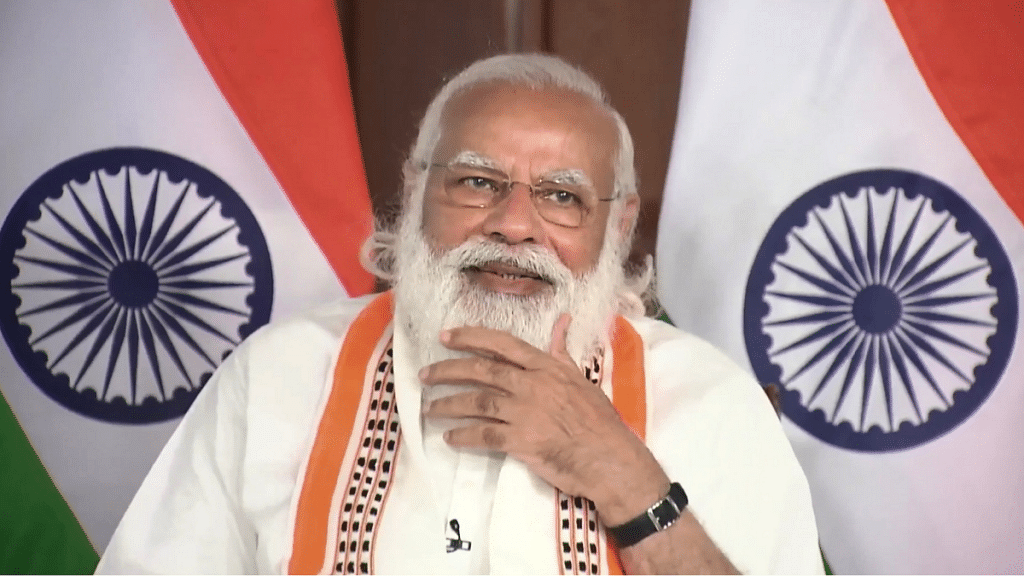

It is only natural to expect that India’s disastrous handling of the Covid-19 pandemic will raise questions about its national capacity. These are questions that naturally bleed over into its effect on foreign and security policies. Several thoughtful foreign policy commentators have criticised the Narendra Modi government for its many missteps, including for prematurely declaring victory and trumpeting India’s success, for its inattention to rebuilding state capacity in the last several years and an excessive focus on public relations and foreign media narratives. Most of these are on point, but despite the scale of the domestic disaster, its impact on India’s external policy may be less serious than imagined.

There are several concerns that have been raised. The most serious is that India will need to turn inward, to focus more on its crumbling health and other infrastructure before it can claim to be a credible and serious foreign policy actor. There is little doubt that India has to necessarily focus on its domestic state capacity. Some of the fastest growing areas of the domestic economy are those that have come up to compensate for the disappearing State, whether it is education or health care or even private security. For example, a 2018 FICCI report stated that the private security sector is now the second-largest source of employment in the country, next only to agriculture, a growth that indicates that the Indian State is failing in the most basic of its functions. And the pathetic state of India’s public health and education infrastructure hardly needs recounting.

Also read: Modi is now a visibly diminished PM, has run out of what he had in plenty these 7 years — luck

Rebuilding task made more difficult

One of the mysteries of Indian public policy is the fact that political leaders have consistently ignored the problem of building state capacity, despite its not inconsiderable effect on carrying out their policies and the likely electoral benefits of improving the administrative delivery mechanism. To take just the Modi government, the failure of both the demonetisation move and the GST rollout can clearly be traced to this lacuna. Irrespective of the wisdom of their specific policies, governments presumably want them to be carried out. Why they fail to recognise that their failures are due to the rotten pillars on which they lean and why they have done so little to rebuild these pillars remains unclear. All we have had so far is tinkering with lateral entry and biometric attendance and such.

The difficulties in undertaking serious reforms to strengthen administrative capacities are no doubt immense. These difficulties are even worse now, when there are dark clouds over the external conditions India faces, with the nation’s security and political interests now threatened by a powerful and aggressive China. This does not make for a very conducive or peaceful condition under which to build national capacities, but there is rather little that India can do about it. India should have undertaken these tasks much earlier when times were calmer and it enjoyed a relatively more relaxed security environment. Having failed to do so when it had the time, there is little choice but to do this now, even under the gun.

Also read: 5 lessons from India’s first wave that can protect livelihoods in the second wave

India isn’t out of play, but only for now

The glaring evidence of India’s poor domestic performance will not significantly dent its attractiveness to the international partners. India may be a clumsy and incompetent giant, but it is a giant nevertheless. Its size, power and potential are all real even if it is often exaggerated in Indian nationalist discourse. This makes India useful to those who are worried about the other, larger, angrier giant in the neighbourhood. India’s partners would no doubt prefer the Indian giant not to trip over its own foot all the time and be beset with frequent bouts of attention deficit disorder, but nevertheless they’ll take what they can get.

This reflects not the quality of what India does but simply the quality of being as large as the country is. As one of the largest and most populous countries in the world, India has a certain heft in an Asian regional context where most others are far smaller. Its military is not capable of doing much to help others directly but India can hold its own along the Tibet border, which forces China to divide its attention, preventing Beijing from deploying the full might of its intelligence and military capacity against East Asia and the US. These are valuable benefits for India’s partners.

These benefits may become less relevant if the Covid-19 pandemic so reduces India that it is no longer able to play a role in countering China. This remains a possibility, especially if India cannot get a handle on suppressing the pandemic. The devastation already caused by the pandemic has no doubt injured and weakened India. However, in international political terms at least, the domestic devastation hasn’t taken India off the board just yet. This is not something to celebrate but to recognise that if the urgent task of building the state capacity is not addressed, India will eventually pay a foreign policy price too in addition to the domestic one.

The author is a professor in International Politics at Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU), New Delhi. Views are personal.

(Edited by Prashant Dixit)