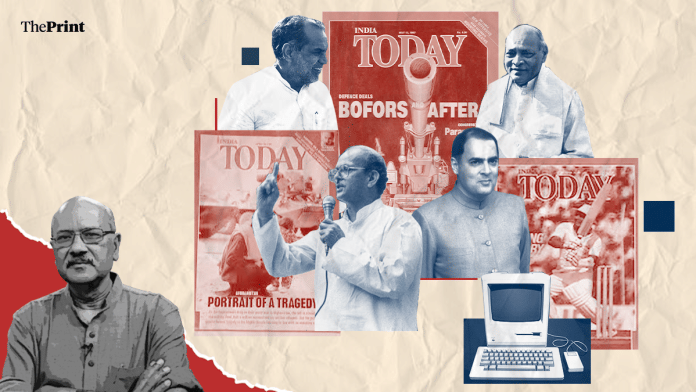

The news magazine India Today just turned 50. It asked me to write on the decade of 1985-95 across which I worked there. The result is this fresh edition in my occasional series First Person Second Draft.

In a Republic still young and evolving, decades would naturally compete to be called the ‘most consequential’. But even put to that test, 1985-1995 would probably have the most stories that dominate our democracy and debates today.

At home and in the immediate neighbourhood, think terminal decline of the Congress after peaking, the first coalitions, Bofors scandal, the Mandal versus Mandir contestation, insurgencies in Punjab and Kashmir, two Indian military interventions overseas (Sri Lanka and the Maldives), two war-like situations with Pakistan (Brasstacks, 1987, and Pakistan’s first ‘nuclear blackmail’ in 1990), a fraught Sumdorong Chu standoff with China (1986-87) and then thaw with Deng Xiaoping, assassinations of Zia-ul-Haq and Rajiv Gandhi, globalisation of Islamist (as distinct from Islamic) jihad and its spread to Kashmir, and the freeing of India’s economy. Although it started with rock-like stability with the Congress at 414 in the Lok Sabha, the decade saw four prime ministers. Isn’t that enough for a mere 10 years?

There’s more. Because of economic reform, a globalising India’s stake and stature in the world rose and just as India Today became the most comprehensive and trusted chronicler of the change at home and around, its pioneering spirit now took its readers to the world. From the Afghan war and Tiananmen Square to the collapse of the Soviet Bloc and the first Gulf War following Saddam Hussein’s occupation of Kuwait. The Cold War ended, as did apartheid, India and Israel became friends. We were also the first magazine to start sending our teams to cover the Olympics, Asian Games and key cricket series overseas.

Also Read: Finding the smoking gun that proved intel before Nellie massacre was ignored, covered up

For good news or bad, for generational shifts and eternal debates, the other decades would struggle to measure up. That all the fears India had had since Independence—political instability, communal and caste divides, decline of a stabilising dynasty, nuclear and terrorist threats, social upheavals, loss of the most trusted ally (Soviet Union)—came true in this decade is one side of the coin. How India responded, learning to trust coalitions, reforming its economy, repositioning itself strategically and leveraging its human resources, is the other. India emerged much stronger, confident and with a rising global presence.

Through these years, India Today was at the heart of this transformation and often at the front. The first enduring reform for this era was Rajiv Gandhi’s push for computers. The first computers for an Indian newsroom, a pair of boxy Apple desktops, arrived in 1985. These were given an exclusive cabin even in a newsroom so constrained for space.

There was a crush for keyboard-time as we discovered the freedom from finger-wrecking manual typewriters and the assurance of the floppy disc. Soon enough, Dilip Bobb, who did the most editing and rewriting, staked one out for himself—or at least pretended to—by having Shirley Joshua, incredible pivot of the process-driven back-end, create a little placard that read, ‘This is the Apple of my eye’, and plonked it on one desktop. That line of control was violated even more frequently and recklessly as the one up north by the bad guys. Since we remember the turning points in our lives, high or low by association, the first story I wrote on one of these desktops was the initial controversy over the Mandal Commission report in 1985. That story endures four decades on.

L.K. Advani’s rath yatra and, ultimately, the Babri Masjid demolition in December 1992 unleashed communal riots across states. Among the bloodiest were in Bombay and the crowded, slummified small towns on its periphery. In its wake came the serial blasts targeting key commercial buildings and neighbourhoods. This wasn’t India’s first trial with a serial bombing. The capital had had some, following the Punjab troubles and massacre of Sikhs. But not at this scale, and not one so clearly traced back to Pakistan. That awful three-letter acronym, ISI, made its appearance and has haunted us since. Gangster Dawood Ibrahim rose from a somewhat comical presence at Sharjah cricket stadium to India’s villain number one, and continues to be so.

Rajiv Gandhi’s instinctive disapprovals of the Mandal Commission report in 1985 sparked a backward caste awakening. Then a series of errors with communal implications—reversal of the Shah Bano judgment, ban on Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses, unlocking of the temple site in Ayodhya. Thereafter, our politics has been a contest between two contrasting ideas. Can you use caste to divide what religion united, or employ religion to reunite what caste divided? Whoever wins, rules India. The Mandal (caste) side had its 25-year epoch from 1989 to 2014—until Narendra Modi reversed the equation in 2014. Now is the era of mandir (Hindutva) and it doesn’t seem to have a half-life of any less than 25 years. The issue is still Mandir versus Mandal. It just played out in Bihar, as it will in Uttar Pradesh in 2027. This decade’s redefinition of national politics has been the most durable in our history. The same applies to political economy. Thirty five years after the reform-led boom, fears and doubts over opening up continue even as we celebrate our successes.

Also Read: India’s ‘dirty little war’ in Jaffna, heroism amid ineptitude & new friendships under fire

The strength and the beauty of India Today, the institution, draws from what a fair, opportunity-laden meritocracy it evolved into. It was unforgiving always, even brutal sometimes. But if you had the hunger, diligence, talent and also a thick skin, nothing—and nobody—could stop you from growing.

When I came into the magazine in 1983 after covering the Northeast, I was warned it was a “five-star” newsroom where unsophisticated Hindi Medium Types (HMTs) would be severely judged and discarded. But India Today evolved. My first cover story for the magazine, by the way, was on Sunil Gavaskar after he scored his 29th hundred to equal Donald Bradman. I had never done any long-form sports writing. It is just that Aroon Purie and Suman Dubey (managing editor then) thought I was the most excited. T.N. Ninan says the India Today newsroom of that era was the dream team of Indian journalism. Proof of the pudding lies in Google. Look at the masthead of that decade and see how far we have reached.

While a clinical meritocracy was key to this, there was also a concept India Today pioneered: the reporter-editor. It wasn’t limited to a reporter rising to be an editor. Nothing at India Today would be so simple. It also meant that even after becoming an editor, you would continue reporting, never mind your multiple editorial responsibilities.

Here’s an example of how we were taught to multi-task. This decade also saw India Today launch its five language editions (Hindi, Tamil, Telugu, Malayalam, Gujarati), which I was asked to helm from 1991 on, in addition to all my other responsibilities and writing. Sometimes, we were exhausted and wished Aroon would acknowledge that. But he wouldn’t. After anchoring an 18-page cover story on the fatwa against Salman Rushdie with a football-team byline from across the world over two unslept nights, I sat on the news desk swinging my legs sort of smug in satisfaction as Aroon passed by. Tell him not to work so hard, Aroon, he will die, said then news coordinator Sandhya Mulchandani, hoping Aroon would acknowledge it. He just said, “Hard work never killed anybody,” and walked on.

At this point, finally, I list the three most important lessons that stay with me:

● There is always the other side to a story. Unless you have checked with that ‘other’ side, no story is publishable. This is non-negotiable. And if somebody complains about a story having been unfair to them, as editor, your default position is on their side. Until your facts check out.

● Anything that comes for free or easy, is loaded with evil. Just say no, or disclose and check.

● And third, be unselfconscious of identity in the workplace. No discrimination, victimisation, exploitation or favouritism based on gender, ethnicity, caste, religion, anything. There’s enough opportunity in this wonderfully meritocratic newsroom. Compete fairly and it will work to everybody’s benefit. In this manner, too, India Today was institutionally prescient. It was ahead of the new middle class consciousness for competitive equality that reform and growth brought in subsequently.

Having joined in 1983, I left in 1995, just as the decade concluded. If, out of the dozen-plus history-defining stories I listed at the outset, I got a piece of all but one—economic reform—I’d say it was a decade’s life well spent, especially in an Aristotelian sense.

Also Read: Life and death of Bhindranwale, one of India’s most dangerous men killed in Op Blue Star

Thank you for this insightful trip back in time.

An AI generated lyrical version of the key events mentioned in this article follows –

The Indian Crucible (1985–Present)

[Verse 1: 1985–1987]

Shah Bano, Rushdie Ban, 414 for the Congress Clan

Sumdorong Chu, Bofors scan, Rajiv has a modern plan

Brasstacks on the desert line, IPKF in the Jaffna brine

Maldives coup, Zia’s end, Deng Xiaoping becomes a friend!

[Verse 2: 1988–1990]

Kashmir heat, Afghan war, Soviets head for the door

Nuclear blackmail, Ninety-one, coalition days begun

Mandal report, Rath Yatra, V.P. Singh and the caste mantra

Saddam Hussein, Gulf War, Tiananmen Square, a world at war!

[Chorus]

We didn’t start the fire

It was always burning, since the world’s been turning

We didn’t start the fire

No, we didn’t light it, but we tried to fight it

[Verse 3: 1991–1992]

Rajiv gone, Sriperumbudur, Open markets, trade is pure

Apartheid ends, Israel ties, India’s global stature flies

Babri Masjid, December night, Bombay riots, communal fight

Serial blasts, city shakes, ISI and the higher stakes!

[Verse 4: The 90s & Beyond]

Dawood on the Sharjah stand, terror reaching across the land

Olympic teams and cricket tours, Chronicling the nation’s chores

Caste divide or faith unite? Twenty years of Mandal might

Twenty-four and Modi’s name, Mandir wins the power game!

[Chorus]

We didn’t start the fire

It was always burning, since the world’s been turning

We didn’t start the fire

No, we didn’t light it, but we tried to fight it

[Outro]

Bihar polls, UP heat, reform doubts and the global beat

Redefining who we are, Mandal/Mandir, near and far…

We didn’t start the fire!

So what happened to Aroooooon Puri.Why is he such a sycophant to Modi now?

India Today has been a part of my life for fifty years as well. Impressed early on by their use of graphics and presentation. 2. The magazine’s archives would be a treasure trove for anyone writing a history of modern India.