The frequent power tussles between the states and the Union, exemplified by the ongoing Supreme Court dispute between the governments of Tamil Nadu and Punjab, and their governors, raise some fundamental questions about India’s federal set-up. They prompt us to ask if India’s federal system can act as a bulwark on the Union’s overreach.

If India’s federal structure was conceived as a key tenet of Indian democracy, how can it survive when the Union can override states’ rights so easily?

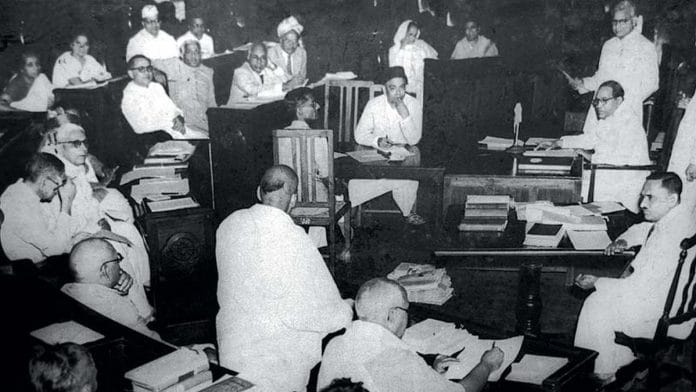

When the Constituent Assembly debated India’s future in 1947-50, the role and powers of the governor were discussed in great depth. At the time, India was broken and divided by Partition, insurgencies, communalism, and colonial rule, so a strong Union to hold the country together was deemed essential. Simultaneously, there was a desire to build a republic where the rights of its 400 million citizens were protected.

Drawing from the experience of provincial governments during the British Raj, the Constituent Assembly grappled with a key question— would governors wield powers akin to the colonial-era viceroys? Concerns arose that if governors were accorded a similar level of discretion under the Government of India Act 1935, this could well be the case. Under this Act, governors could appoint and dismiss governments at will and withhold assent to legislation. In essence, governors could bypass elected state governments.

Also Read: Governor vs govt not new in India but Constitution doesn’t guarantee a solution

Fear of overreach

At the core of the Constituent Assembly’s discussions on the governor’s role was a fear of executive overreach.

For instance, in May 1949, Shibban Lal Saksena (UP) weighed in on the wide ambit of powers accorded to the Union government: “So the party in power at the Centre will nominate all the Governors in all the provinces. It will also nominate all the Judges of the Supreme Court and other big officials. That is not a good thing. I cannot subscribe to the view that a single person should have the power to nominate all these high officers. We should remember that absolute power is not a good thing. It corrupts absolutely.”

Saksena’s point must be viewed in the broader context of the Union’s immense powers over the state, spanning the judiciary, diplomatic service, and other institutions— entities that are meant to act independently from the Union, if needed.

Rohini Kumar Chaudhary of Assam took a more explicit stance on how the governor’s powers could threaten the Constitution itself.

“Sir, just as a piece of cow dung may spoil the whole vessel of milk, this particular provision will spoil this whole Constitution of ours,” he said during a 2 June 1949 discussion on Article 147 (now 167), which defines the duties of the chief minister to the governor.

Also Read: Governor vs CM spats once did the impossible — unite CPI(M) and BJP

A history of overreach

It is clear today that these apprehensions were not baseless. The executive’s overreach has shaped the trajectory of the Union, especially in the first few decades of independence.

The impact of the ambiguity around the governor’s powers is clear especially with the abuse of Article 356 to impose a state emergency. This Article gives the President the authority to transfer a state’s legislative and executive powers to the Union.

Since 1947, President’s Rule has been invoked more than 130 times. The greatest number of instances were reportedly when Indira Gandhi was in power (50 times between 1966-1977 and 1980-1984), followed by the Janata Party (20 times between 1977-1980).

More often than not, this intervention was more to suit a political agenda than to resolve a true breakdown in constitutional functioning.

The power of the Executive to declare a state emergency was significantly curtailed only after the 44th Amendment to the Constitution in 1978 and the Supreme Court’s landmark 1994 S.R. Bommai judgment.

Since then, however, governors have found other ways to stifle elected assemblies by using their powers under Articles 163 and 200. Under Article 163, “the decision of the Governor in his discretion shall be final, and the validity of anything done by the Governor shall not be called in question on the ground that he ought or ought not to have acted in his discretion.”

Under Article 200, Governors can withhold assent on bills, send them to the President for review, and then send them back to the Assembly for reconsideration. In times of a hung assembly, they can invite parties to form the government. Unlike the President of India, who is bound by the advice of the Union cabinet, theoretically, the governor can override the decision of a state Assembly.

Currently, the clash between non-BJP states and the Union stems from the fact that governors can employ a pocket veto on legislations by not addressing them, returning them, or forwarding them to the President for a decision. Consequently, between the governments of Punjab, Tamil Nadu and West Bengal, an estimated 35 bills are awaiting assent.

Governors have also tried to meddle in electoral politics. For instance, in 2020, when Uddhav Thackeray was Maharashtra CM, his nomination to the Legislative Council was withheld by then governor Bhagat Singh Koshiyari until the eleventh hour. Without this approval, Thackeray would have had to resign as CM.

Over the last two years, the governors of Kerala and Tamil Nadu have threatened to ‘withdraw their pleasure’ on the appointments of state cabinet ministers, hindering the elected government’s functioning.

Also Read: Should the office of Governor be removed? Bad idea to give CM more executive power

A rival political base

The ongoing governor-government conflicts validate the fears expressed by many members of the Constituent Assembly— an unelected authority could act as a rival political base to an elected chief minister, further exacerbating Union-state tensions.

It is then worth asking why the Constitution accorded this power to the Union.

KM Munshi, Jawaharlal Nehru, and Sardar Patel, among others, argued that governors would provide support to fledgling states and quell potential secession threats.

More importantly, there was a push to ensure governors remained “detached” from local politics so that they could provide more objective assessments of the conditions in the states. In Nehru’s words, a governor should be someone who is removed from the “party machine”. He elaborated: “On the whole, it probably would be desirable to have people from outside— eminent people… who have not taken too great a part in politics. Politicians would probably like a more active domain for their activities but there may be an eminent educationist or person eminent in other walks of life, who would naturally, while cooperating fully with the Government and carrying out the policy of the Government, at any rate helping in every way so that policy might be carried out…”

BR Ambedkar argued that despite the vagueness of this article, the interpretation is clear: the governor is bound by the advice of the state government.

Nonetheless, he failed to outline pathways for redressal against a governor, beyond going to the President, who, in turn, was bound to act on the Union government’s advice. The challenges of Partition appeared to dominate the thinking of the Assembly at the time. The hope was that experienced administrators would take on this role, which has indeed materialised on occasion— from Sarojini Naidu in UP in 1947 to Gopalkrishna Gandhi in West Bengal in 2004.

The Indian Constitution has done a remarkable job of upholding and building the strength of the Union for the last 73 years. By acting as a bedrock and standard for politics, it has helped the country navigate complex linguistic, social, and religious divides. It has evolved to build a single market, linking the entire country together and has formally recognised the importance of devolution in ensuring better development. At the heart of this successful experiment has been India’s federal structure.

However, through a vestige from the colonial era, the Union is able to subvert Indian democracy, and in turn, the will of the electorate.

Vibhav Mariwala is an independent researcher. He tweets @VibhavMariwala. Views are personal.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)