China is facing many challenges to get past the barriers to innovation, a problem that Zhongnanhai—CCP headquarters—may be trying to address by promoting party cadres with technical training or ‘technocrats’.

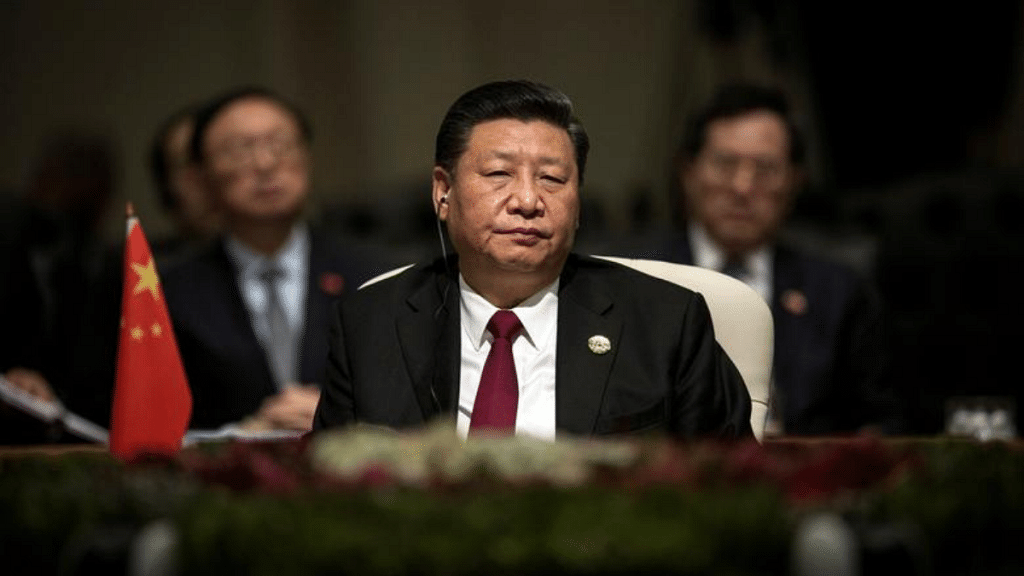

President Xi Jinping’s techno-utopia-driven national security State needs bureaucrats who can provide solutions to the domestic and foreign policy challenges he has outlined.

The 20th Party Congress now has 40 per cent ‘technocrats’ — occupying 81 seats — as full members of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), according to an analysis by Brookings Institution. Among the 24-member Politburo selected at the 20th Party Congress, at least six new members have formal training and experience in the science and technology fields. Four of them have studied outside of China.

There is some debate among Chinese scholars about what technocrat means.

“Chinese technical elites came to power only partially because of their technical credentials and partly because of their non-technocratic political or family connections. The emphasis on three objective elements – technical education, professional occupation, leadership position – avoids value judgements and thus is less subjective,” wrote Cheng Li in his 2001 classic text Chinese Leaders: The New Generation.

‘Technocrat’ interests

Among the technocrats promoted by Xi, certain subject experts are particularly sought-after, including aerospace technology, semiconductors, environmental sciences, and biotechnology.

Ma Xingrui, the current chief of the party’s Xinjiang unit, was chief commander in China’s space programme before being elevated to the Politburo. He rose from the position of Guangdong province governor. Yuan Jiajun, party secretary of Zhejiang province, who was affiliated with the Chinese space programme as well, has been elevated to the Politburo.

Ma and Yuan are sometimes described as members of the ‘aerospace clique’ because of their affiliation with China’s space programme. The elevation of the so-called ‘aerospace clique’ or ‘cosmos club’ can’t be missed. Approximately 20 seats on the 20th Central Committee have a background in aerospace technologies, according to an analysis by Brookings Institution.

Li Gangjie, a Tsinghua University graduate in industrial physics and nuclear safety, who has served in the environmental sciences portfolio, has been promoted to the new Politburo. Li also briefly studied in France between 1991 and 1993 before returning to China. Yin Li, former party secretary of Fujian and now party secretary of Beijing, is trained in public health and received his education in the former Soviet Union and the United States.

Also read: Climate challenge and ‘Chinese-style modernisation’ aren’t at odds with each other for Xi Jinping

A history of decline and rise

The struggle between party cadres with technocratic training and political theorists has a history going back to former Chinese President Jiang Zemin. In 1997, when Jiang was the General Secretary, the share of ministers with technical training — including engineering — was as high as 70 per cent. The phenomenon was visible across various sections of Chinese politics during the late ’90s when even a large majority of the members had science and technology degrees.

But under Hu Jintao in 2007, the percentage share of technocrats who were full members of the Central Committee of the CCP, fell to 31.3 per cent, further declining to 17.6 per cent under Xi Jinping during the 19th Party Congress.

Although the numbers may hint towards Beijing’s growing concern around promoting home-grown innovation, the story is more complicated.

The return of the technocrats since 1997 marks a decade-long competition between Beijing and Washington over next-generation technologies — including artificial intelligence, machine learning and semiconductors — intensifying further in the last two years.

The Chips and Science Act in August and the semiconductor export controls announced in October suggest that Washington is willing to strike where it hurts Beijing. The two measures that seek to ensure the US can maintain its edge are semiconductor technology against Beijing and thwarting China’s efforts to acquire semiconductor-related intellectual property through unfair means.

If these announcements weren’t enough, the US National Security Advisor said that Washington needs to maintain a lead over the competitors in foundational technologies as much as possible.

“Competition to develop and deploy foundational technologies that will transform our security and economy is intensifying. Global cooperation on shared interests has frayed, even as the need for that cooperation takes on existential importance. The scale of these changes grows yearly, as do the risks of inaction,” says the US National Security Strategy of 2022.

Also read: China sets up new Politburo with two members who have India history

Why Xi is comfortable promoting technocrats

Another explanation for promoting technocrats may be factional politics.

“They are less tied to political factions because they are functionals working in silos. They are less corrupt because they are more educated. So, officials from these two sectors first came up because [of] what Xi wanted to exclude. They did not get their start because of what Xi wanted to include,” wrote Desmond Shum, an exiled Chinese business tycoon with insider knowledge of Chinese politics, in a Twitter thread.

Shum was alluding to the fact that the technocratically bent cadre has a mindset of working in silos and hence may not muster the ability to gather political capital the way Xi Jinping did in the lead-up to his rise to power.

Other experts have echoed Shum’s views on why Xi feels comfortable promoting the technocrats.

“Generally, more down-to-earth compared with cadres from other streams. This will be a tight-knit team that understands technology and with a goal-oriented mindset,” said Wu Junfei, a researcher at the Hong Kong-China Economic and Cultural Development.

Xi’s focus seems to be on promoting individuals who have delivered major military and scientific projects. Sichuan province governor Huang Qiang is one of them. He has contributed to the design of the Chengdu J-20 stealth fighter. But it can’t be assumed that Xi is putting merit ahead of his political interests.

His promotion of a technocratic cadre serves two purposes. First, the promotion of these skills ensures China is ready to compete against the US in foundational technologies. Second, the new generation of technocrats is unlikely to have the political acumen to challenge Xi’s authority anytime soon.

Xi’s success lies in using political theory, with support from his ideological Tsar Wang Huning, to promote his brand of a ‘national security State’. But the underlying impulse of marrying political theorisation with science and technology is to ensure domestic economic growth – ultimately ensuring regime stability.

The new Politburo members with science and technology backgrounds will likely jockey to enter the next Politburo Standing Committee in 2027. These new cadres will not have the type of political acuities that Xi’s recent rivals, Li Keqiang and Hu Chunhua, have demonstrated.

Xi is looking towards the newly promoted technocrats to achieve his home-spurred scientific innovation goal and ensure they can’t challenge him at the next Party Congress.

The author is a columnist and a freelance journalist. He was previously a China media journalist at the BBC World Service. He tweets @aadilbrar. Views are personal.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)