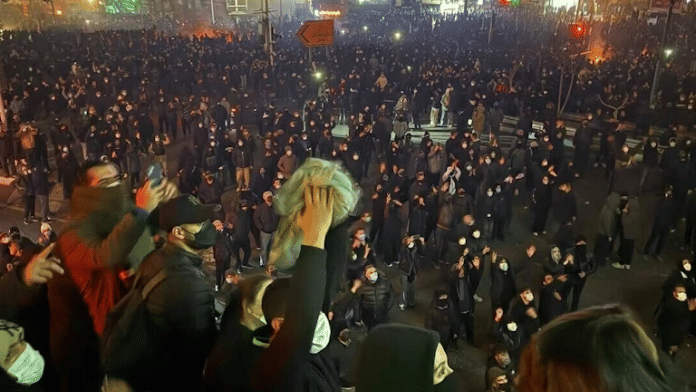

US President Donald Trump on Monday announced on Truth Social a 25 per cent tariff on Iran’s trading partners. In Chinese analyses, the move is viewed as exploiting Iran’s widening domestic unrest, marked by protests across more than half the country amid soaring inflation and a collapsing currency, and as a form of economic coercion infused with political signalling.

One Chinese commentary described the tariff threat as “loaded bullets”, aimed at warning the Iranian leadership while siding with the opposition forces. It framed the move as part of a broader regional strategy, illustrating how America is exploiting domestic unrest for strategic gain.

In this reading, given China’s position as Iran’s largest trading partner, the message is directed as much at Beijing as at Tehran.

Downplaying the unrest

Much of Chinese commentary treats Iran’s protests as serious but not regime-threatening. Qiu Zhishu, a Chinese cultural worker based in Tehran, argues that the demonstrations are fragmented, decentralised and lack the capacity to stir the regime change. Social discontent exists, he notes, but it remains limited in scope and is unlikely to destabilise Iran. Targeted actions against key figures could provoke backlash, but the protests themselves are generally seen as low-risk.

This cautious reading extends to external pressure. Qiu suggests that US and Israeli actions are calibrated to weaken Iran without provoking direct confrontation, warning that escalation could trigger a broader Iranian response given Tehran’s strategic position and leverage over oil exports.

These views reflect a wider Chinese tendency to emphasise regime resilience and caution against overstating the impact of what they are calling as ‘street mobilisation’.

Online discourse reinforces these themes. On Weibo, hashtags such as “Iran does not seek war but is prepared to fight” and “Ample evidence shows US and Israeli involvement in recent Iran unrest”, promoted by state-owned media, gained significant traction. These narratives intersect with growing concern in China over what is described as an emerging “iron triangle” linking China, Russia, and Iran, as well as Western unease about this alignment.

Qiu Zhongmin, professor at the Institute of Middle East Studies at the Chinese University of Foreign Studies, frames US rhetoric as a form of cognitive warfare. By amplifying allegations of Iran’s “suppression of the people”, Washington, he argues, seeks to generate pressure and strategic uncertainty.

Oil and beyond

Chinese commentary highlights the economic risks of instability in Iran. One Weibo post lamented that China’s investments in Venezuelan and Iranian oil are “about to be robbed by American robbers”, putting trillions in investment at risk. A Baijiahao commentator emphasised that Iran’s stability is closely tied to China’s energy security, noting that any disruption would have immediate domestic and global consequences. Another Weibo post warned that “the US already controls Venezuela. If it controls Iran too, only Russia will remain on China’s oil route.” Iranian crude accounts for nearly 15 per cent of China’s oil imports, while almost half of its total crude comes from the Middle East.

Chinese analyses caution that strikes, transport disruptions, or threats to shipping through the Strait of Hormuz could temporarily push oil prices up by US $15–20 per barrel. Given Iran’s export capacity and strategic location, such disruptions are seen as a greater threat to global supply than unrest in Venezuela.

As one commentator put it, “When the Middle East catches a cold, global oil prices sneeze.” For China, turmoil in Iran would translate into immediate pressure at the pump. Beyond energy, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is also vulnerable. China and Iran cooperate extensively on railways, pipelines, and port construction, and political instability could disrupt operations and undermine long-term investments.

Some Chinese commentary employed vivid metaphors to convey these anxieties. One analysis argued that amid the chaos of the Middle East, China’s “development feast” is bound to be splashed with oil. Iran is described as a “VIP private room” within the BRI, where energy and infrastructure cooperation is heating up like a simmering stove.

This raises a recurring question in Chinese discourse: should Beijing eventually act as a peacemaker or focus on safeguarding its own interests?

Also read: Iran protests and the moral confusion of Liberals

India in the picture

Chinese analysts also situate Iran’s unrest within the broader context of regional competition with India. Commentary points to China’s support for Iran through initiatives such as the 25-Year China–Iran Comprehensive Cooperation Agreement and Beijing’s role in facilitating Israeli-Saudi rapprochement at a difficult moment for Tehran. Yet this influence is constrained by India’s presence. Some observers highlighted that Iran continues to lease Chabahar Port to India, a strategic hub linking Central Asia to the Indian Ocean, even as the China-backed Gwadar Port develops nearby. The 2024 renewal of India’s operating rights at Chabahar, accompanied by an additional $370 million investment, is cited as evidence of Tehran’s careful balancing and of the limits of China’s leverage despite its economic and diplomatic engagement.

Consequently, as of yet, China’s approach to the unrest in Iran is likely to remain cautious, seeking to safeguard its economic and energy interests while navigating the broader geopolitical risks. The situation underscores the delicate balance Beijing must maintain between asserting its influence, securing energy stability, and avoiding entanglement in regional conflicts that could disrupt its strategic objectives.

Sana Hashmi is a fellow at the Taiwan-Asia Exchange Foundation. She tweets @sanahashmi1. Views are personal.

(Edited by Aamaan Alam Khan)