For the last two decades, my interest in tennis has been driven by pretty much one thing – Roger Federer. This is a bit of an embarrassing admission for someone who reported from Wimbledon and who was once much more Catholic in his tastes. I grew up, after all, poring through Tennis magazine that my father subscribed to, was glued to Doordarshan telecasts of live Wimbledon matches and was a fanboy of many other tennis greats—particularly of the precociously talented John McEnroe.

But Wimbledon 2003, Roger Federer’s first Grand Slam victory, changed all that. By then, it was clear that the gauche ponytailed young man was preternaturally gifted. He flowed slickly through the draw, needing no more than his dancing feet, his clever hands, and his easy flair to defuse the contrasting and seemingly unsophisticated aggression of Andy Roddick (semis) and Mark Philippoussis (final). I remember a couple of commentators back then predicting that Federer was likely to become one of tennis’ greatest players, a forecast that some regarded as premature and foolhardy. But to anyone who watched, his genius was already in plain sight.

Also read:

Future of the past

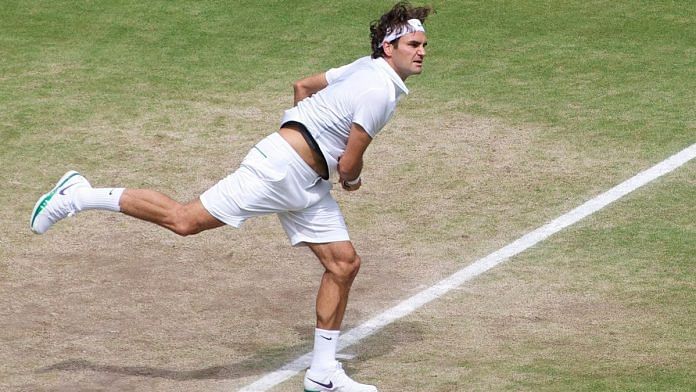

The most fascinating thing about Federer was that even as he signalled he was tennis’ future, he seemed like a creature from a wistful pristine past. His game did lie centred in modern tennis’ twinned core: topspin and power. Of course, Federer had a fair measure of both, but they only supplemented his game, never defined it. He didn’t overcome his opponents by blasting them out of court or wearing them down by heavy and relentless percentage topspin. They were taken apart in gentler ways – disarmed, disengaged, detached by a style of play centred around the old values of balance and precision, helped immeasurably, of course, by the unbearable lightness of his feet and the fastest hands on the tour.

His single-handed backhand, a stroke that has been all but passed over for the more powerful, topspin-friendly but unattractive double-hander, was a thing of compelling beauty. Yes, he struggled with it when the ball came up chest high as it frequently did from Rafael Nadal’s viciously spun crosscourt forehands. But Federer would remind us of his genius every now and then by finding the smallest of openings to thread a backhand ever so precisely down the line. A 2014 article in The New York Times titled The Death of the One-Handed Backhand described it quite accurately as not “simply a stroke” anymore, saying it has become “the last redoubt of artistry in tennis, a final vestige of the sport as it was traditionally played.”

Also read: Not work ethic, fighting spirit or tenacity, Nadal’s ability to ‘handle’ injury sets him apart

Greatest of all time

Much has been written, and much will continue to be, about who is the greatest player of the modern era. Novak Djokovic, with 21 Grand Slam wins (and probably a few more on the way), and Nadal, with 22 (who is ageing but can never be ruled out on the slow red clay at Roland Garros), are already ahead of Federer, who has 20. But Grand Slams alone are not a true index of a player’s worth. Can we ignore Federer’s record 103 ATP (Association of Tennis Professionals) tour titles or his streak as World number one for 237 consecutive weeks, the longest in history?

At a larger level, while records matter, they can be misleading and rarely tell the whole story. To take an example from cricket, was Geoffrey Boycott, with his average of 48.16 as an opening batsman in Test cricket, greater than Gordon Greenidge (45.21) and Conrad Hunte (45.07)? Or perhaps even more incredulously, was Sir Geoffrey almost on par with Sachin Tendulkar (50.30) as an opener?

If Federer packed the tennis courts and lit up television screens, it is because he could do things with a tennis racquet that were unmatched, and that too with a composure and grace. We watched him for his signature inside-out forehands, the astonishingly nonchalant volley flicks from the back of the court, his silky flowing drive volleys and, of course, that seemingly wanton but razor-sharp backhand down the line. He brought a certain joy and beauty to a game that was in dire need of it.

Federer’s retirement may be, as it has been routinely noted in the press, the end of an era. But for me, and I suspect many of us, it is also the end of a certain kind of relationship with tennis. We will continue to admire the old – the extraordinary athleticism of Djokovic and the single-minded doggedness of Nadal. We will eagerly watch the progress of the new—young stars such as Carlos Alcaraz and Casper Rudd. But somewhere in our minds, it will be hard to erase the images of Federer, particularly when he was on song. There is no doubt in my mind that he will live longer in tennis memory than other players of his generation. If this is a measure of greatness, then he was simply the best—ever.

The writer teaches philosophy at Krea University and was the Editor of The Hindu. He tweets @muk22. Views are personal.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)