India’s judiciary, a cornerstone of its democracy, is at a critical juncture today. The system is laden with innovations like Public Interest Litigations and Lok Adalats, which were designed to make justice accessible. Yet, it grapples with an overwhelming backlog of over 40 million cases. If left unchecked, courts may take decades to clear this backlog with their current capacity. Speaking of capacity, we are at less than half the Supreme Court’s recommended 50 judges per million citizens. Unsurprisingly, the average case resolution time is 30 months, starkly contrasting the approximate six months in the European Union. This protracted pendency erodes public trust and imposes a significant economic burden, estimated at 0.5 per cent of India’s GDP. As Laveesh Bhandari argues, this economic burden usually results from locked assets, increased legal costs, and the expectation of judicial delays, incentivising businesses to remain in the informal sector.

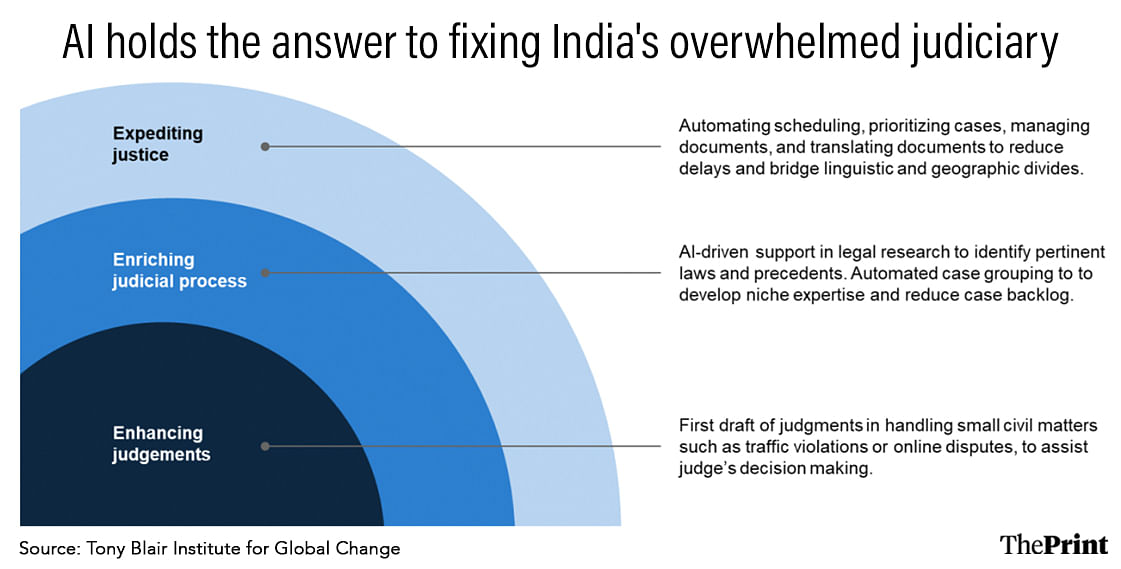

The introduction of e-Courts in mission mode is a breakout move. By digitising cause lists and case statuses, this reform has enhanced transparency and trimmed delays. Chief Justice of India, DY Chandrachud, rightly emphasised the necessity to “harness the processing power of technology to its fullest”. As Indian courts start embracing technology, there is much it can help accomplish in expediting, enriching, and enhancing the judicial process.

On expediting justice, technology, especially automated case management systems, can alleviate the administrative load on courts. By automating scheduling, case prioritisation, and document management, these systems reduce procedural delays — crucial for the 77 per cent of Indian prisoners awaiting trial. For instance, Germany uses IBM’s AI assistant, OLGA, for metadata extraction, accelerating case processing. The US is exploring similar AI applications, with a special committee examining its usage. Moreover, AI’s capability to bridge linguistic and geographic divides in India’s complex legal landscape could be transformative. With just 0.1 per cent of India’s budget allocated to the law and justice ministry, AI’s potential to address resource gaps, especially in underserved areas, could be revolutionary.

AI-powered tools can help enrich court proceedings through automated support in legal research to identify pertinent laws, statutes, and precedents. Companies like Lex Machina and Ravel Law analyse past judicial rulings to help lawyers and judges make more informed decisions. Moreover, AI tools like DoNotPay, originally a chatbot for fighting parking tickets, have expanded to offer various services, including categorising similar legal cases. Thomson Reuters offers Westlaw Edge, a legal research platform that uses AI to identify similar cases and issues, allowing judges and lawyers to access grouped information for faster case handling. Automating case grouping could reduce the burden on legal systems, particularly in high-volume areas such as civil litigation, traffic courts, and small claims. These ‘bundles’ of similar cases can be disposed of in special courts, helping accelerate case resolution, allowing judges to develop niche expertise, and reducing the backlog of cases.

Also read: ‘Govt of the people’ has transformed into ‘administration of things’. AI powered it

Some risks involved

Most interestingly, AI can even deliver judgments by analysing historical case data, precedents, and relevant statutes. China is piloting AI-based smart courts, particularly in handling small civil matters such as traffic violations or online disputes. Estonia is exploring using AI to adjudicate small claims cases involving amounts less than €7,000. That said, courts typically include a final human review of the AI-generated judgment to guarantee that biases and hallucinations that AI is notorious for don’t creep in and deny justice.

Other risks from AI also need to be managed, from data privacy concerns addressed by proper redaction to managing biases related to gender, caste, or socio-economic status leading to unfair outcomes. Further, ensuring that translation or infrastructure limitations, especially local courts, do not widen the digital divide or disadvantage any group.

In all of this, it is critical to note that this AI serves as a decision-support system, not a decision-making system. The potential of AI extends to fostering efficient, effective, and equitable judiciary, which in turn bolsters public trust in justice. As the Supreme Court acknowledges the vast capabilities of AI, it has started translating several thousand judgments into multiple regional languages through SUVAS (Supreme Court Vidhik Anuvaad Software). High courts in states like Punjab, Haryana, and Manipur are experimenting with AI tools for legal research. Further, organisations such as indikaAI’s Nyaay are championing powerful use cases to advance the responsible use of AI in the judiciary.

With the SC leading the discourse on AI use, Indian courts must ready themselves for large-scale tech use by strengthening digitisation and data collection. The implementation strategy should start by setting clear goals, assessing readiness, and identifying priority applications. Parallelly, extensive efforts are needed to standardise processes, enhance privacy standards, and foster grievance mechanisms to realise this technological potential. Finally, courts must also partner with the private sector, to supercharge innovation while maintaining strict standards and overseeing enforcement. As we move ahead, a transparent and phased implementation will be key in integrating AI into the judiciary, ensuring it complements rather than replaces human judgement, revolutionising India’s pursuit of justice.

The author heads the India practice for the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change. Views are personal.

This article is part of a series on AI tech policy and impact as part of ThePrint-Tony Blair Institute for Global Change editorial collaboration.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)