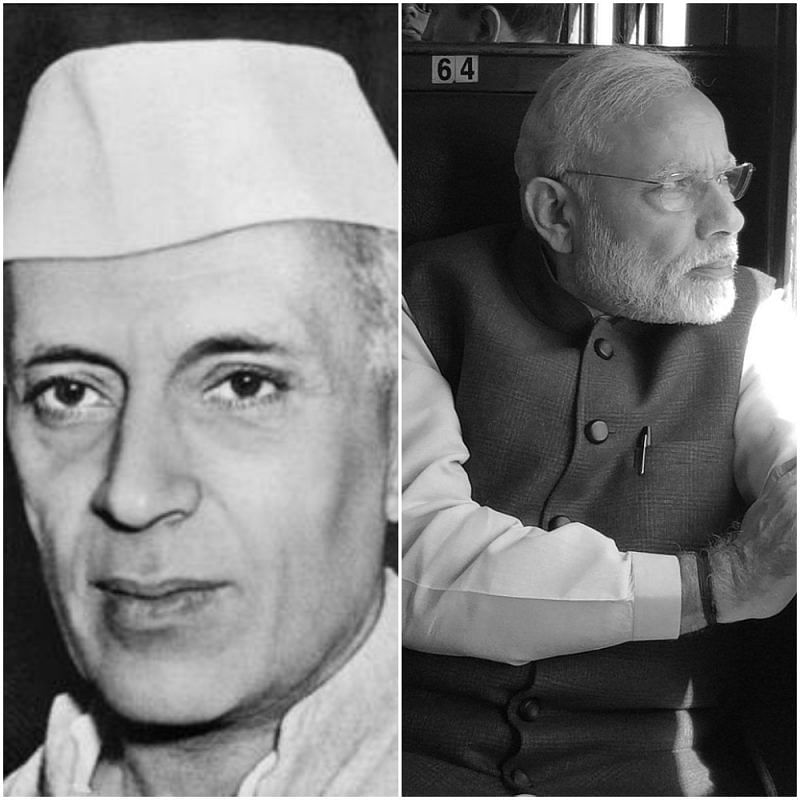

It was easy for Nehru to be a “democrat” and institution-builder given every lever of the state was in his hands.

Nehru controlled the presidency, both Houses of Parliament and every state government throughout his 17 years in power — with the brief exception of Kerala. It is easy to be a “democrat” and institution-builder when every lever of the state is in your hands.

Today’s India is a democracy with robust checks and balances, enforced by a judiciary far more empowered than in Nehru’s day. Our Supreme Court’s judgements on privacy, triple talaq and Diwali crackers would have been unthinkable in 1950s India or today’s China (leave alone in Mao’s China during the Cultural Revolution or the Great Leap Forward). And numerous opposition state governments and the Rajya Sabha act as further checks on Modi.

When faced with an elected opposition government for the first time in 1957 (Kerala led by the redoubtable EMS Namboodiripad), Nehru failed the democracy test. Within two years, he instead misused the colonial-era device of a governor acting at the Centre’s behest to dismiss an elected state government. That his daughter Indira was Congress president at the time added a dose of dynastic nepotism to the mix, but the buck stopped with Nehru (not Indira) in 1959.

Even his esteemed colleague, Maulana Azad (who had been Congress president from 1940 to 1946) had to reserve his criticism to an edition of his book that could only be opened 30 years after his death. Contrast that with Raghu Rajan’s potshots at the government of the day last month, and the RBI’s attempt to statistically demolish the demonetisation narrative at the end of August.

And despite his avowed atheism, Nehru built his political brand on the moniker of “Panditji”, explicitly calling attention to his high-caste status. He was always “Pandit Jawaharlal” in the vernacular press – while remaining impeccably rational and “secular” in the English-language press.

But even Nehru’s relatively dictatorial powers were far from unfettered in the way that Mao’s and Stalin’s were. Their unfettered dictatorship enabled them to perpetrate pogroms such as the decimation of the “kulaks” in the 1930s and the Great Famine that followed in the wake of Mao’s quixotic Great Leap Forward — each killing tens of millions of people.

Nothing of the sort can ever happen in India. Indira during the Emergency did suspend the restraining influence of the judiciary and parliamentary opposition, but even she eventually called an election to bolster her legitimacy.

Indira’s was not an unfettered dictatorship, since the Statesman, The Indian Express and Kuldip Nayar didn’t lose their critical voices during the Emergency. But that controlled experiment in autocracy did deliver East Asian style economic outcomes.

Morarji Desai delivered even better economic outcomes in the next two years of democracy, averaging 6.5% annual GDP growth (the fastest 2-year growth before 1980) with modest deregulation combined with a dose of swadeshi a la George Fernandes. George’s expulsion of Coca-Cola and IBM helped spawn the world’s best cola (Thums Up) and the software behemoths of TCS and HCL.

If anything, dictatorship (albeit somewhat fettered dictatorship by comparison with Mao) enables Xi Jinping to indulge his hubristic fancies, especially on China’s imperial claims in the South China Sea and the Himalayas.

Democratic India has called Xi’s bluff on Doklam, just as Vietnam called Deng’s bluff in March 1979. Despite having more dictatorial power, Jawaharlal tried to avert his eyes when confronted with the PLA having built a road through the vast Aksai Chin area of India’s territory in Ladakh.

Ironically, China’s territorial gains at India’s expense in the 1950s (Tibet first, then Aksai Chin) occurred mainly because Jawaharlal was abridging the flow of information. In a more democratic era, Modi has responded robustly in Doklam and PoK (last year). Effective strategic leadership is always the best response, especially when democracies are confronted by aggressive autocracies.

The author is an adjunct professor of Economics and Global Affairs at the SP Jain School of Global Management.