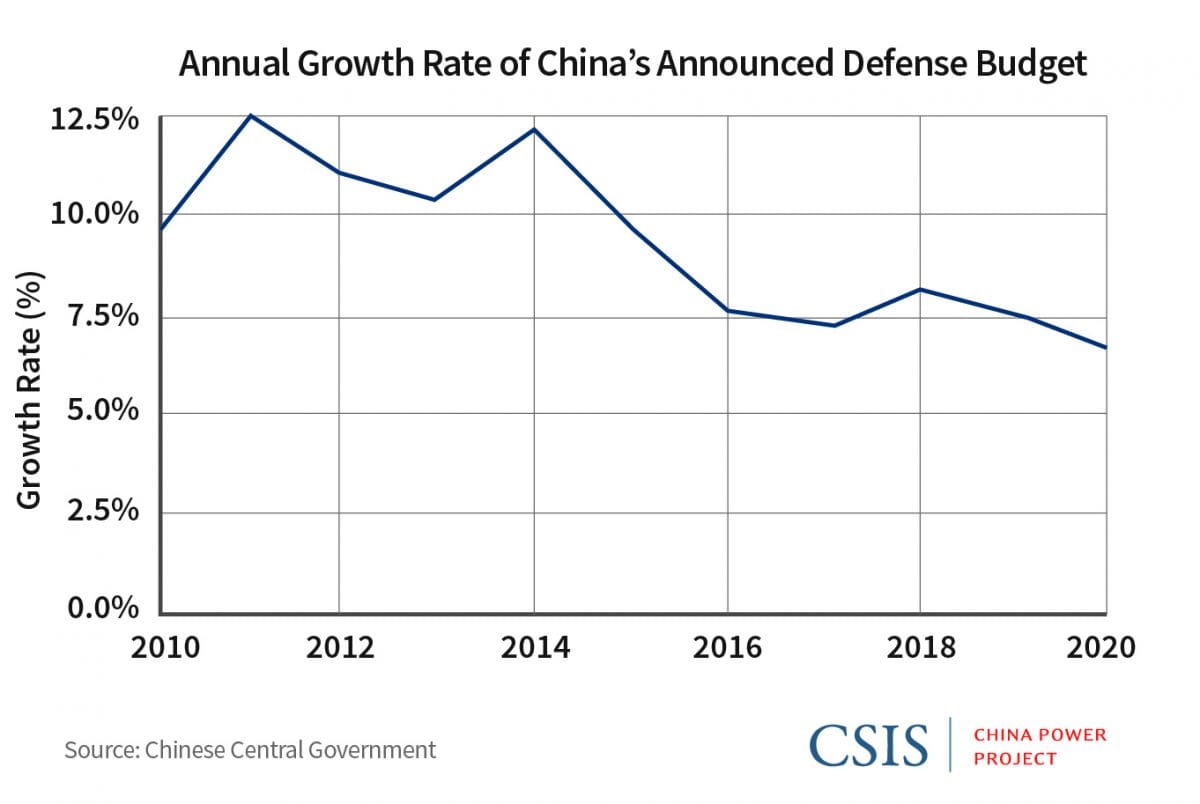

China kicked off the annual meeting of its legislature, the National People’s Congress (NPC), in Beijing on Friday, 22 May. The first day of the NPC session featured the widely anticipated announcement of China’s new defence budget. Chinese officials revealed that spending on national defence in 2020 would rise to 1.268 trillion yuan, an increase of 6.6 per cent — the lowest in decades.

Since 2016, year-over-year growth in China’s defence budget has ranged between 7.2 per cent and 8.1 per cent. While the announcement of a 6.6 per cent increase in defence spending in 2020 marks a significant downtick, it must be understood in light of the recent slowing of the Chinese economy. For the first time since China began publishing GDP targets in 1990, Chinese leaders did not set economic growth rates for the economy this year, as a very low rate of growth is expected due to Covid-19. The IMF estimates that China’s GDP will grow by only 1.2 per cent in 2020. By comparison, China’s GDP grew by 6.1 per cent in 2019 and the military budget grew by 7.5 per cent.

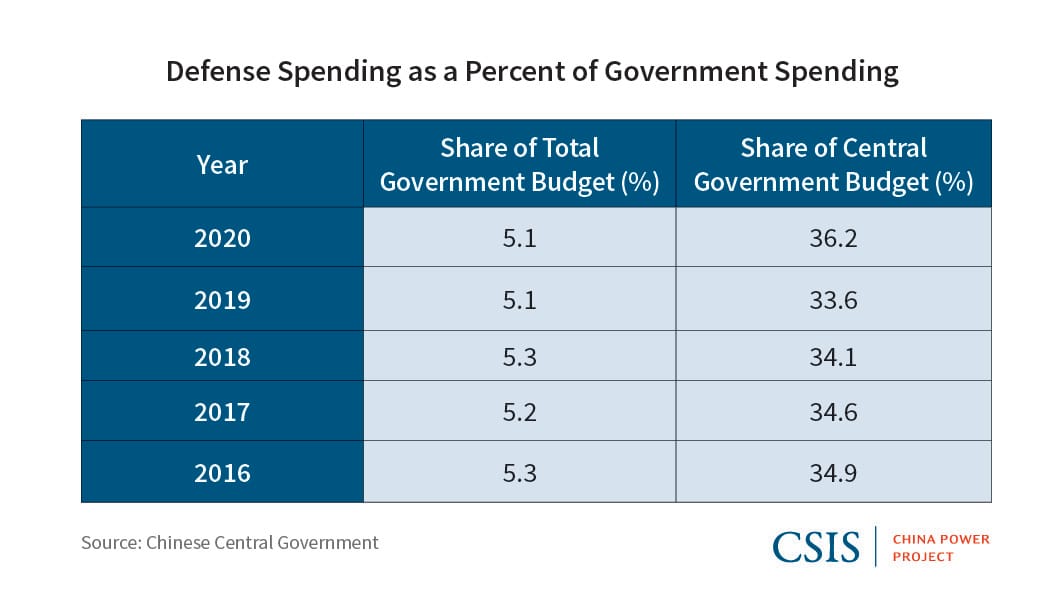

Looking at expected government expenditure provides additional clarity. While the central government budget is slated to fall by 0.2 per cent, total national government spending (which includes the central government spending) will increase by 3.8 per cent as leaders work to stimulate the economy. Spending on the military as a per cent of the overall national government spending will rise slightly from 5.06 per cent in 2019 to 5.12 per cent in 2020, and spending as a per cent of the central government budget will rise from 33.6 per cent to 36.2 per cent.

Given the economic consequences of Covid-19, China’s recent increase in defence spending sends a clear signal that President Xi Jinping remains committed to completing the modernisation of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) by 2035 and transforming the PLA into a “world-class” military by 2049.

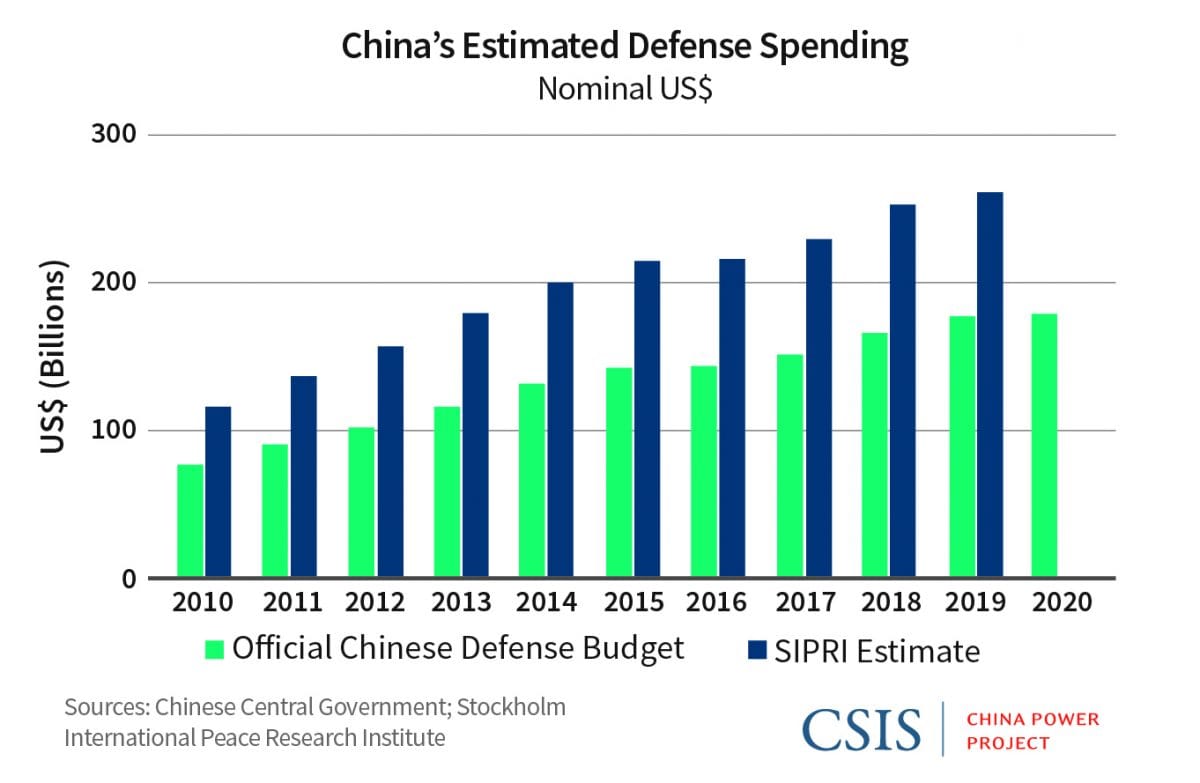

One noteworthy caveat is that inflation does play a role when looking at overall trends in defence spending. In nominal US dollars, the official 2020 budget amounts to around $178.6 billion (conversion rate of 7.1) compared to a budget of $177.5 billion (conversion rate of 6.7) in 2019. When using constant 2010 dollars to account for inflation, China’s expected defence spending appears to dip from $143.8 billion in 2019 to $140.5 in 2020. (Constant 2010 values are calculated based on GDP projections.)

The official Chinese military budget only tells part of the story. The Chinese government has in the past been inconsistent in its reporting on defence spending. China’s 2019 defence white paper, for instance, provides military spending figures that are slightly higher (between $2-3 billion each year) than the announced defence budgets. This discrepancy may be the result of the defence white paper including costs associated with militia forces in its figures.

Efforts to precisely pinpoint Chinese military spending are further complicated by the absence of a detailed breakdown of expenditure and the exclusion of various military-related outlays, including spending on the People’s Armed Police (PAP). The PAP is a paramilitary police component of China’s armed forces that is under the command of the Central Military Commission (CMC) and charged with internal security, law enforcement, counterterrorism, and maritime rights protection. A draft law revision that is being considered by the NPC would put the PAP under both the CMC and the Communist Party’s Central Committee. The official budget for the PAP was 179.78 billion yuan ($28.5 billion) in 2019.

Foreign estimates of Chinese military spending suggest that actual spending may be much higher. In 2019, the Chinese government reported an official defence budget of just under $178 billion, while the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) estimates actual (nominal) spending to have been $261 billion. The International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS) provides estimates that are typically lower than those of SIPRI. In 2018, IISS estimated Chinese defence spending to be $225 billion, while SIPRI put the number at nearly $254 billion. The official budget that year was just $167 billion.

Bonnie S. Glaser is senior adviser for Asia and the director of the China Power Project at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). Matthew P. Funaiole is a senior fellow with the China Power Project and senior fellow for data analysis with the iDeas Lab at CSIS. Brian Hart is a research associate with the China Power Project. Views are personal.

This article was first published by the Center for Strategic and International Studies.