Recent reports suggest that India is negotiating with the US for “co-production” of two state-of-the-art and proven weapon systems— the Stryker Infantry Combat Vehicle and Javelin Anti-Tank Guided Missile. The proposed plan is to ‘Make in India’, but with absolute transfer of technology and future development. This raises some serious questions.

Are we shelving ‘atmanirbharta’ in defence with respect to high–end military technology? What happens to the Indian Army’s two–decade-long quest for indigenous alternatives—the Futuristic Infantry Combat Vehicle (ICV) and a next-generation Anti-Tank Guided Missile (ATGM) —to replace the current aging and near-obsolete inventory of ICVs and AGTMs? Or is it an interim solution to bridge India’s military tech gap even as domestic development of weapon systems based on emerging technologies continues.

The opinions of defence analysts are divided on these projects. On one extreme are the arguments for remaining on course for indigenous futuristic development, with domestic interim solutions, to protect the interests of our defence industrial base. On the other extreme, it is argued that given the long gestation period of development and induction expected for the next two decades, the best option is to pursue ‘make in India’ initiatives with absolute transfer of imported cutting-edge technology, as well as collaborative upgradation and future development.

Before proceeding, a clear-eyed stock-taking of India’s ICV and ATGM predicament is crucial.

Also Read: Indian military has narrowed the gap with PLA in drone warfare, now it needs a clear concept

Aging ICV fleet

The mainstay of mechanised infantry battalions is the ICV BMP-2, which was inducted in 1986 and later produced in India. The life of an ICV is typically 32 years, and out of 2,500 BMP–2 vehicles, 1,500 are now obsolete. However, after structural evaluation, it has been decided to extend their life to 40-50 years, despite the escalating costs of overhaul, repair, and upgrades. About 1,000 out of the fleet are fitted with a thermal night sight, but no other upgrade of the BMP–2 has been carried out so far.

After an effort of two decades, it is only now that a contract has been signed with Armoured Vehicle Nigam Limited (AVNL) to upgrade 693 BMP-2s. Upgradation of another 811 BMP–2s has been proposed. While upgradation is planned only for night sights and fire control system, it should ideally also include a more powerful engine, a third–generation ATGM, and anti–UAV protection measures. This project is fraught with uncertainties as the ATGM and protection systems have yet to be identified, and the whole process may take up to a decade.

The Futuristic Infantry Combat Vehicle (FICV) was conceived in 2004, with the Ministry of Defence approving its development and production in October 2009. The project was launched twice through Expressions of Interest in 2010 and 2015, but was prematurely shelved due to dithering within the MoD. In 2021, a Request for Information was re-issued, and the project was finally approved in February 2023 for the production of 1,750 FICVs by the Defence Acquisition Council. AVNL, alongside private-sector companies such as Larsen & Toubro (L&T), Mahindra Defence Systems, and Tata Motors, are expected to bid for this programme.

In a nutshell, the life of outdated BMP-2s has been extended, with its upgradation approved only in March 2024 and set to fructify in next 10 years. Meanwhile, the FICV project is yet to take off and will likely take 10 years to develop and another decade to fully replace the fleet.

It’s important to note that the Infantry Protected Mobility Vehicles (IPMVs) fielded by indigenous manufacturers and bought by the Army in limited numbers are not ICVs. These are Armoured Personnel Carriers (APCs), a cheaper solution for our regular infantry deployed in the plains and high–altitude areas.

In my view, there exists a case for inducting approximately 1,000 state–of–the–art ICVs to meet the interim requirements of the Army.

Outdated ATGMs

The Indian Army has a large inventory of approximately 6,000 second-generation ATGM launchers. Each infantry battalion in the plains is equipped with eight FLAME launchers firing the Milan-T2 missile. In the mechanised infantry, each BMP-2 of carries a Concourse missile launcher, while T–90 tanks are equipped with 9M119M missiles fired through the main gun. However, all these missiles lack ‘fire-and-forget’ capability. They are only capable of direct horizontal attack, which is defeated by the tank’s reactive armour, restricting their use against ICVs and other soft targets.

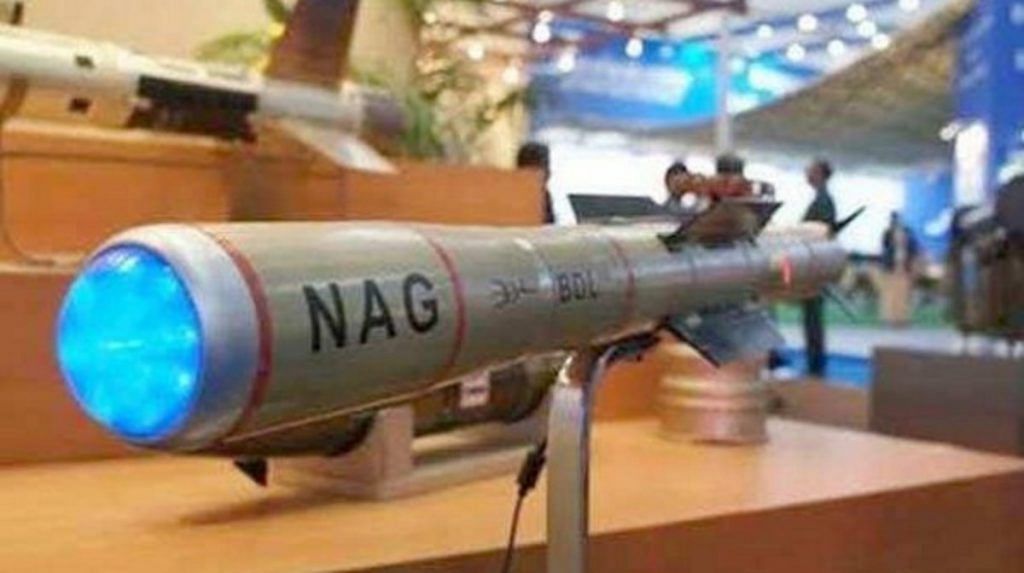

In 2019, a limited number of third-generation, fire-and-forget, top-attack Israeli Spike ATGM launchers were procured as an ‘emergency purchase’. A repeat order was placed in 2020. An order was also placed for 13 third-generation Nag Missile Systems (NAMIS), earlier known as Nag Missile Carrier (NAMICA)—modified BMP-2 with six Nag ATGM launchers—for mechanised infantry (reconnaissance & support) battalions.

India’s quest for a state-of-the-art, third-generation ATGM with fire-and-forget, top-attack, and tandem warhead capabilities began in 1983 with the establishment of the Integrated Guided Missile Development Programme.

Under the Nag umbrella project, the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) is currently developing several ATGMs. Prospina, the base variant, is a land-attack fire-and-forget ATGM with top attack capabilities and a range of about 4 kilometres; it can also be mounted on the NAMIS platform. Helina/Dhruvastra, a helicopter-launched version, has a range of 7-10 km. Field trials are ongoing for the Man Portable Anti-Tank Missile (MPATGM) designed for infantry and special forces. The Standoff ATGM (SANT), an upgraded Helina variant, offers a range of 20 km for deployment by indigenous drones. The Semi-Active Mission Homing (SAMHO) ATGM is tube-launched and will also be adapted for launch from tank guns.

The NAG project is a classic example of the time it takes to develop high–end military technology.

To bridge this gap, India almost signed a deal with the US for the Javelin ATGM in 2009, but it fell through due to disagreements regarding technology transfer. India then negotiated with Israel for the Spike ATGM, but it fell short of the required parameters in field trials. As a result, the focus shifted back to the development of the indigenous Nag MPATGM. While the Nag ATGM demonstrably possesses state-of-the-art capabilities, its refinement and full-scale induction are likely to take another decade. To date, no Nag ATGM has been inducted, underscoring the urgent need to bridge this technology gap.

Also Read: No Viksit Bharat 2047 without a national security strategy. PM Modi’s legacy on the line

A windfall—Stryker and Javelin

It is a matter of speculation as to how the Stryker and Javelin negotiations came about. There seems to have been no immediate proposal from the Army. As mentioned earlier, we ourselves were seeking the Javelin in 2009.

It’s likely that the US, aware of our travails in acquiring state-of-the-art ICVs and ATGMs, seized the opportunity to showcase its military cooperation. They’ve reportedly offered a ‘Make in India’ deal for the Stryker and Javelin, promising complete technology transfer, upgrades tailored to our General Staff Qualitative Requirements (GSQRs), and continuous cooperation with relevant vendors for future development. It is also possible that these developments are linked to the mega deals for MQ-9B Sea/Sky Guardian drones, F414 fighter jet engine technology, and the general push to promote the US defence industry. Ultimately, this seems to be a political decision made at the National Security Advisors’ level.

The Stryker, a state-of-the-art wheeled ICV, has been in service with the US Army since 2002. It has two main variants—the Infantry Combat Vehicle and the Mobile Gun System (MGS), which is a light tank featuring a 105mm gun. The Stryker also has eight other configurations for various support roles. It can be utilised to equip mechanised infantry battalions operating in high-altitude areas, reconnaissance and support battalions (assuming we persist with this archaic concept), and reconnaissance subunits within mechanised forces. It can also function as a light tank. Our total requirement would be around 1,000-1,200 units. It is pertinent to mention that the FICV project will include both tracked and wheeled versions

Then, there’s the Javelin, currently the world’s best ATGM. A shoulder-fired, third-generation, fire-and-forget ATGM, it has horizontal and top attack capabilities with an electronic countermeasure (ECM) package and a 2,500-metre range. It could be employed by infantry battalions, special forces, and even integrated onto BMP-2s in our mechanised infantry battalions.

In terms of scaling these systems, we need to consider a judicious mix between ATGMs and loiter drones. To this end, we could insist on the Switchblade 600 ‘suicide drone’ as an add-on to the package.

The production and induction can be phased and controlled while we continue developing and fielding our own indigenous futuristic systems.

The contracts for both deals should be carefully worked out to ensure comprehensive transfer of technology, including India-specific add–ons, current and future upgrades/refurbishments as applicable to the US Army, and participative future development with the vendor.

The Indian Army should leverage the windfall opportunity presented by the proposed Stryker ICV and Javelin ATGM projects to bridge the technology gap while continuing to develop and field futuristic indigenous FICVs and Nag ATGMs.

Lt Gen H S Panag PVSM, AVSM (R) served in the Indian Army for 40 years. He was GOC in C Northern Command and Central Command. Post retirement, he was Member of Armed Forces Tribunal. Views are personal.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)