China has already embarked on an ambitious ‘expand geography’ project through OBOR, forays into the South China Sea, building a string of pearls in IOR.

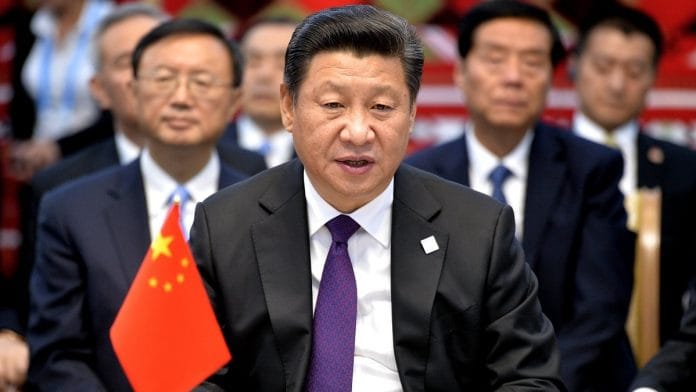

The new Chinese Year of the Dog began with a major announcement. The Chinese Communist Party’s proposal to do away with the cap on the term limit for the president of the country has become a subject of intense debate not only among China watchers abroad but also within the country. This paves the way for Xi Jinping to stay on as President after 2023.

China’s Constitution has been amended twice, once in 1988 and again in 1993, but both these amendments were economic. In the wake of German unification, the disintegration of the erstwhile USSR and the failure of Marxism to tackle the issue of growth and poverty, Deng decided to change the ideological template to market economy while keeping the C-word, (Communist). Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao added their trademark ideas and successfully carried the Communist Party with them. But their terms ended uneventfully, crediting them as harbingers of a new China.

During the 19th Congress, Xi Jinping made the third amendment. The top man in China requires enormous courage, administrative power and unrestrained authority to change the Constitution. Xi has all these and additionally commanded unquestioned loyalty, evoked fear among colleagues and above all professed zero tolerance for dissidence. The 19th People’s Congress demonstrated that Xi Jinping, after Mao, was the de-facto ‘Chairman’.

The post of Chairman was first introduced in March 1943, when the Politburo at that time decided to remove Zhang Wentian as General Secretary. Mao Zedong, the unquestioned leader of the party since the Long March, was named as Chairman of the Politburo of the CPC Central Committee. But he consolidated his power and position as People’s Republic of China’s first chairman and chief of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). As a dictator, ruthless administrator and a cult supremo, Mao presided over a decade of the Cultural Revolution, mass executions of intellectuals, party loyalists, dissenting pro-democracy leaders and hardworking peasants. After Mao’s death in 1976, it was Deng Xiaoping who reigned supreme and continued the dictatorial regime of a one-man rule but restored the post of President through the 1982 Constitutional amendment restricting the office to two five-year terms.

Pro-democracy protests reinforced the need to assert dictatorial state while the merciless crackdown on pro-democracy protesters in Tiananmen Square in 1989 revived the apprehensions of another era of cruel dictatorship of the Oligarchy and return of the new “Gang of Four”.

Xi got the 19th Congress to elevate him to a higher pedestal with no competition. The implicit significance of this move was enormous, which many in the West, failed to grasp. It was not a mere clichéd expression when Xi remarked about the beginning of a ‘new era’ in his opening address. ‘Chairman’ Xi left nothing to imagination about his intent when he unveiled the picture of China “moving closer to centre stage”. Xi Jinping’s move to anoint himself as ‘Emperor’ is a prelude to his vision of expanding the ‘Chinese Empire’.

China has already embarked on an ambitious ‘expand geography’ project through Xi’s flagship OBOR, forays into South China Sea, building a string of pearls in the Indian Ocean region, expanding footprints in the choke points in IOR and eyeing the countries in the Indo-Pacific, all amounting to adding 30 per cent of additional geography to China.

Beijing’s wide-ranging re-balancing strategy to win over ASEAN countries, prop up Pakistan-type satellite states, overwhelm Africa with aid in exchange of enormous rich resources manifold times are only some of the strategic steps towards regional power consolidation. As second largest economy of the world, Beijing is only a few statistical points away from dislodging the USA from the coveted post of global super power and super cop.

But all this projection of Chinese Empire will not go unchallenged. Within China, there is a lot of political and economic churning under way.

Ten days before the Constitution amendment announcement, on 13 February, Sun Zhengcai, an important leader with strong following in the party and considered a front-runner in the race to succeed Xi, was indicted on corruption charges. His whereabouts are since not known. Ten days later, Yang Jing, a close aide to Prime Minister Li Keqiang, was dismissed as a state councillor and demoted for “serious disciplinary violations” and accused of “colluding with law-breaking businessmen and society people”. Many members of the Communist Youth League, Yang was one of them, have been dismissed from party posts and their perks taken away as punishment for “posing serious threat to the party”. These may lead to re-groupings within the CPC and pro-democracy outfits. In addition, there is mounting corruption at all levels of the party and the PLA, unrest in Uyghur and Tibet, sagging economy, and debt-ridden partners.

Outside China, there are other factors that will act as a combined bulwark against the asymmetrical Chinese dream of Xi Jinping: changing power equations in Indo-Pacific and India’s own emergence as a soft but strong economic power in the region with a greater global engagement and positive role in world affairs.

The Preamble of the Chinese Constitution says, “The future of China is closely linked to the future of the world”. Xi Jinping may wish to amend it and say, “The future of the world is closely linked to the future of China”.

The author is security and strategic affairs commentator and former editor of ‘Organiser’.

The sagacious decision to keep government functionaries away from events arranged by the Tibetan diaspora to mark sixty years of exile reflects a welcome recognition of the reality of China’s changed role in the world. A harmonious reset of the relationship is in India’s best interests.