Though this has not evoked the kind of attention it should have, the assembly poll in Maharashtra was one election that journalists got right.

In the run-up to that election—and especially after the results of the Lok Sabha polls—the conventional wisdom was that the BJP was a goner in Maharashtra. As for Eknath Shinde’s Shiv Sena, it was seen as a transient phenomenon that would soon be forgotten.

But as the campaign progressed, nearly every journalist I spoke to who had travelled through Maharashtra began saying that the conventional wisdom was wrong: that Shinde looked like he and his Sena were here to stay, and that the BJP-Shiv Sena alliance would win Maharashtra.

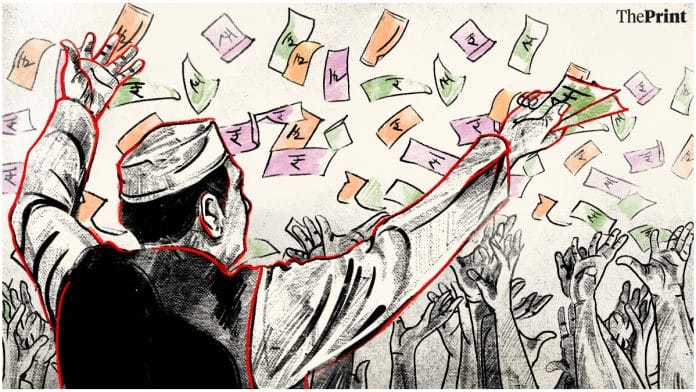

The reason for this turnaround, the journalists said, was the women’s vote. Shinde had successfully appealed to female voters by launching the Ladki Bahin programme, which is effectively a cash transfer scheme. These women voters had changed the way in which the polls were going.

In the aftermath of the election, the BJP-Sena’s appeal to women voters has become the standard explanation for the results on all TV programmes and election analysis articles.

I do not dispute this analysis. I just think that we are taking too narrow a view of the results. The point is not just that the BJP-Sena government won the election by appealing to women voters. The larger point is that the alliance turned its fortunes around by making cash transfers to voters.

This is one more example of how politics works today: elections are won by parties that make actual transfers of cash to voters. And yet politicians are sometimes reluctant to admit that the prevailing trend in Indian politics is to abandon development agendas in favour of simply sending cash to voters.

Also Read: BJP is winning elections without Modi. Congress needs to change its strategy

‘Revdi’ for some, reform for others

Take the example of the BJP. When the Congress introduced the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA) in 2005, the BJP (including Narendra Modi) bitterly opposed it, along with other such schemes. More recently, the Prime Minister has made sneering references to parties that give revdi (freebies) to voters and suggested that this is a terrible thing to do.

In fact, the BJP’s rhetoric is more than a little hypocritical. The broad rule is: when others do it, it is revdi. When the BJP does it, it is a great step forward for the Indian masses.

In an important article in the Hindustan Times, published the day after the election result, Roshan Kishore made the point that the BJP has often fallen back on cash transfers when it is not sure it can win on the basis of its record. Kishore argues that the results of the 2019 general election, which we often attribute mainly to the Balakot air strike, were also due to Narendra Modi‘s PM-KISAN program, which he describes as a “retrospective—send cash now, verify eligibility later—scheme.” Kishore also argues that when the BJP doesn’t send money to voters (the 2024 interim budget is his example), it does relatively badly in the elections that follow.

Of course, it’s not just a BJP practice. Other parties do it too. One reason for Hemant Soren’s victory in Jharkhand was his Maiya Samman scheme. Increasingly, chief ministers who believe in cash transfers to the poor have worked out that as long as you send the cash in the months leading up to the election, you can neutralise any anger and disappointment with your performance.

Welfare for the win

That transfers have become such a reality of Indian politics is not something that anyone expected in 2005, when the Congress launched the NREGA scheme. Sonia Gandhi argued that while economic liberalisation had transformed India, it had failed to deliver benefits to the poor. She said that whenever she travelled through India’s villages, she felt that nothing had really changed for the poor.

This was not a view shared by Manmohan Singh, who as finance minister had been the architect of liberalisation in 1991. Singh believed in the formal economy and its ability to deliver change and benefits to all Indians. Sonia argued that while this may well be true in the long term, it was taking too long for the poor to see any benefits.

These two ideological strands led parallel lives during the tenure of the UPA. Sonia and her National Advisory Council (condemned by many dedicated liberalisers as a collection of jholawallas) advocated for more direct transfers and loan write-offs, while Manmohan Singh and his economist colleagues worried that such measures could distort the economy.

The success of UPA-1 lay in Sonia and Manmohan being able to find common cause and launching welfare schemes. That legacy has endured longer than the UPA itself.

It is the reason why incumbent governments tend to do much better at elections: they have the ability to transfer cash to voters. And every party, no matter what it may say in public, follows some variation of this principle.

The consequences for Indian politics are more fundamental than Sonia or Manmohan could have foreseen.

Also Read: If Gujaratis have such a good deal, why are they leaving and going to the US?

Middle class, who?

Nobody disputes today that all political parties depend on corporate fat cats to fund their election campaigns. The allegations about the BJP and Gautam Adani are the subject of current headlines, and during the last Lok Sabha campaign, the Prime Minister actually named Adani and Mukesh Ambani as industrialists who sent tempos full of money to the Congress.

So, no matter who gets elected, the fat cats and billionaires are always okay.

For the poor, it is direct transfers, welfare schemes, and the distribution of benefits that increasingly determine who they vote for. They vote once they have got some immediate benefit.

That leaves the middle class. Many members of the middle class, who were once avid supporters of Narendra Modi, have complained, especially after the last Budget, that their interests are being ignored. With the stock market faring badly—perhaps partly due to capital gains tax changes introduced in the last Budget—and tax rates not being tweaked to account for inflation, the anger has only grown.

And yet the government pays no attention to middle-class complaints or even to middle-class interests.

If you’ve ever wondered why that is so, here is your answer: if a government knows how to accommodate the fat cats and has worked out how to win the votes of the poor with direct transfers, then it doesn’t need the middle class.

Yes, it was nice to have its support at the very beginning. But, hey, things change!

Vir Sanghvi is a print and television journalist, and talk show host. He tweets @virsanghvi. Views are personal.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

Very incisive and well reasoned point of view.

Sorry, vir. The cash transfers under ladki bahin yojna were made to many middle class women. The urban middle classes are really the upper middle class if you look at India’s income distribution .

Nice report from Vir Sanghvi! I strongly feel, the article talks about the truth. I can see lots of comments from BJP supporters who target Vir and they don’t talk anything about the facts and substance of the article. BJP always spreading hatred and don’t know to counter with facts. Typical BJP fellows

This is an individual’s opinion. Individual who is known for his hatred for BJP. There is very serious credibility problem here.

We surely don’t need vir shangvi !!!

Mr. Sanghvi, what are you upset about?

You never supported them nor will you ever support them. So what explains your whining?