Two countries in India’s northeastern neighbourhood, Bangladesh and Myanmar, are heading for elections in 2026. The implications extend far beyond questions of democratic process.

Security, connectivity, regional influence, and long-term stability converge in a rare situation in India’s northeastern frontier. Though both countries have different political structures, the logic behind the upcoming elections has many similarities. While Bangladesh is trying to transition from an unelected interim government to an elected one, Myanmar is shaping an electoral process under a military regime.

However, in both cases, there seems to be an urgency to claim legitimacy. In Myanmar, post the 2021 coup, the military junta became increasingly isolated in the international community. With the emergence of the National Unity Government (NUG), an umbrella entity that brought together various ethnic armed organisations (EAOs), aiming to forge a democratic alliance, the pressure built steadily on the junta. Additionally, the house arrest of former State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi and the exclusion of the National League of Democracy (NLD) from the upcoming elections have placed the junta’s role in the country’s political process under scrutiny.

Nevertheless, the first phase of elections is slated for 28 December, and the military-backed Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP) is positioned for victory. The chances are that the world will reluctantly accept the electoral results. Meanwhile, resistance to the elections will continue. The recent announcement of the Spring Revolutionary Alliance, which consists of 19 EAOs involved in direct confrontation with the military regime, signals a prolonged conflict.

On the other hand, the military junta reportedly started the prosecution of over 200 people for violating its stringent voting laws and attempting to obstruct elections. The punishment could be as severe as the death penalty. For the time being, one thing is clear: the elections will not bring a resolution to the conflict but will create a reconciliatory framework. It is within this context that most of Myanmar’s neighbours will recalibrate their relations with the newly formed government.

Threat to Northeast

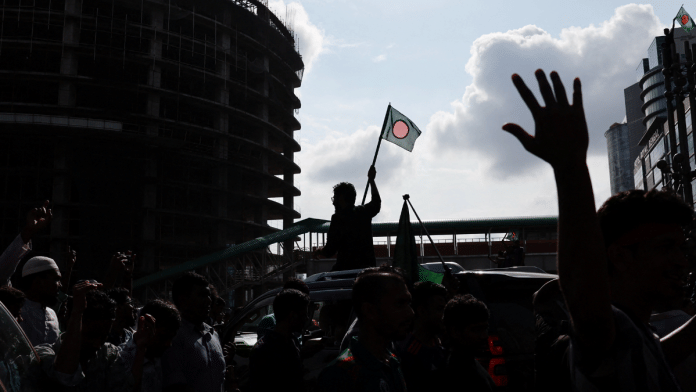

The case of Bangladesh is more complicated. Sheikh Hasina, much like her counterpart in Myanmar, has been ousted from power. Elections have been announced for 12 February, but the Awami League has been banned by the Muhammad Yunus-led interim government under the Anti-Terrorism Act. Bangladesh’s International Crimes Tribunal, a domestic war-crimes court, has also recently handed down a death-penalty verdict against Sheikh Hasina. Dhaka has formally sought Hasina’s extradition, but New Delhi has so far shown no inclination to comply. India’s refusal has, however, become a flashpoint in Bangladesh’s volatile political climate, triggering protests outside the Indian High Commission in Dhaka. Demonstrators have accused New Delhi of protecting the former prime minister.

Additionally, the resurgence of Islamist groups in Bangladesh has coincided with heightened anti-India rhetoric. The Yunus-led interim government has been lenient, allowing Islamist-leaning figures greater space within administrative structures. Several figures, including National Citizen Party leader Hasnat Abdullah, have threatened to shelter anti-India forces. This rhetoric has been reinforced by Muhammad Yunus on many occasions. He recently referred to the Northeast as “landlocked,” while provocative “Greater Bangladesh” maps have appeared across Dhaka. Though none of these references reflect capability, they do normalise and amplify anti-India sentiments. The recent death of radical leader Sharif Osman Hadi, a polarising figure known for his strong anti-India rhetoric, has triggered violent protests. Meanwhile, minorities remain in danger, and Islamist groups continue to get a free run under the Yunus government.

Herein lies the critical difference between the situations in Myanmar and Bangladesh. In Myanmar, India has been able to walk the tightrope between the military junta and the EAOs. There is a definitive absence of any anti-India sentiment. In Bangladesh, the political turmoil has created fertile conditions for radical Islam hinged on anti-India sentiments. While elections in Myanmar are a forgone conclusion, any hope for elections to take place in Bangladesh, even in a constrained form, rests on the intense competition between political stakeholders, including Muhammad Yunus himself, who wants to desperately legitimise his position.

Both elections have risks for India because legitimacy deficits rarely remain internal. There is always a possibility of immediate and tangible spillover to India’s northeastern borders, considering the region has historically been sensitive to insurgencies and external interference. From Indian insurgent groups operating from Myanmar or ISI training insurgents in Bangladesh, India’s northeastern borders will feel the consequences of any turmoil in either country.

Without a political resolution, external influence will continue to grow in India’s backyard. Myanmar’s military junta already relies on China for economic lifelines and mediations with EAOs. And Myanmar owes 40 per cent of its foreign debt to China. In Bangladesh, Chinese involvement in the upgradation of Mongla and Chattogram ports, power and grid assets and Huawei-linked telecom networks close to India’s eastern seaboard and the Northeast raises concerns about its dual-use potential.

Also read: Violence over Osman Hadi is about Islamist Bangladesh. India-baiting is a distraction

No clear winner for India

The US has also been widely held responsible for the regime change in Bangladesh and for backing the NUG against the military junta, both in the name of democracy. Recent developments would suggest that the US has not scaled back its interest in the region. It was not too long ago that the Trump administration, in an unprecedented move, lifted sanctions on the military junta leaders. This was also in lieu of critical earth mineral contracts in Myanmar that were being discussed in Washington. These developments took place after the announcement of the much-criticised Humanitarian Corridor that was proposed in Bangladesh.

Beyond the United States and China, Russian interests are deeply embedded in Myanmar, while a growing Pakistan and Turkey axis is taking shape in Bangladesh. One would hope that the two elections in India’s neighbourhood will resolve New Delhi’s concerns about its northeastern neighbourhood becoming a fulcrum of geopolitical contestation. However, the reality is that electoral processes alone are unlikely to counter the great geopolitical contestations or ideological alignments in a region where stakeholders are viewing political transitions as opportunities for legitimacy and strategic opportunity rather than democratic renewal.

Finally, there is no clear winner in either election that India can back. Instead, the challenge is to prepare for strategic engagement with all stakeholders. At the same time, India must prepare for the inevitable spillovers. Whether it is illegal immigration, continued conflict, trafficking of weapons and narcotics, securing India’s borders must remain a priority, and radical rhetoric from across the border must be firmly and consistently countered.

The 2026 elections are milestones, not just for Myanmar and Bangladesh but also for India. Regional stability will not be determined by the outcomes of these elections but rather on India’s diplomatic manoeuvrability – its capacity to anticipate instability, shape outcomes, and decisively manage external interference.

Rami Niranjan Desai is a scholar of Northeast region of India and the neighbourhood. She is a columnist and author and presently Distinguished Fellow at India Foundation, New Delhi. Views are personal.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)