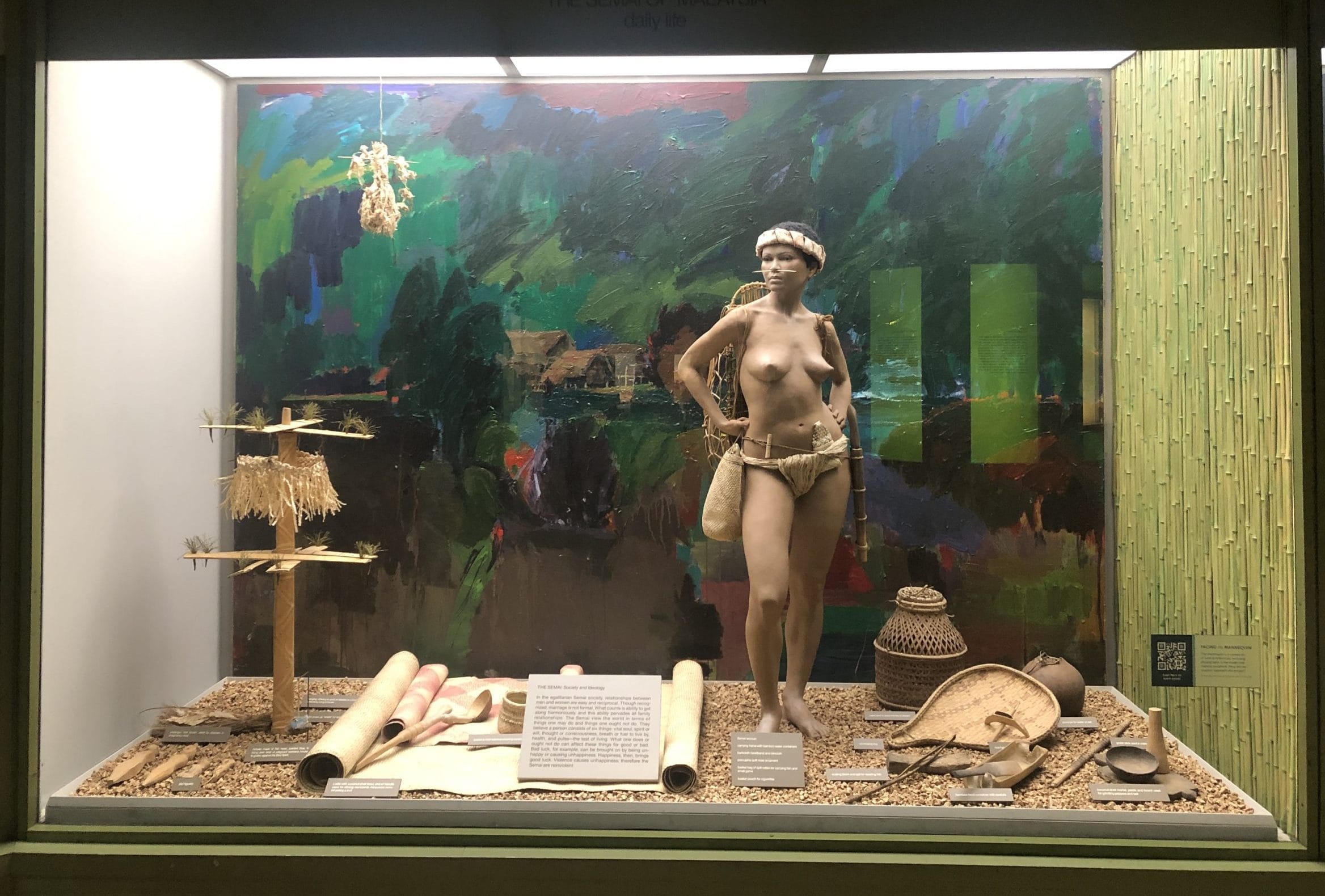

As we moved past the airless dioramas of stuffed dead tigers, rhinoceroses, and elephants lining the “Hall of South Asian Mammals,” my kids and I found ourselves at the entrance of a “Hall of Asian Peoples.” This hall too featured dioramas starring stiff, stricken-looking mannequins of Asians of various subcultural “types”—the first, strikingly bare-breasted, represented an allegedly “primitive” culture. The flow from one hall to the other triggered the sickening impression that Asian people were being displayed as a subset of Asian mammals.

We were at New York City’s American Museum of Natural History, one of the world’s most visited museums, drawing 4.5 million tourists and local visitors annually. Its cultural footprint expanded massively after it was featured in the popular 2006 movie Night at the Museum. Visitors are largely drawn by the museum’s dinosaurs and planetarium, but it also houses exhibits on human cultures that attract significant crowds.

Museums are not just meant to preserve the past for us like time-capsules, but to curate it to reflect current understanding. But at this museum, both the exhibitions and their curation are stuck in a time warp. Visiting the “Hall of Asian Peoples” and “Hall of African Peoples” felt like stepping back into a much older American mindset. In a time of deep reflection on the roles of colonialism, slavery, and racism in American history, it was astonishing to find such a prominent museum still mostly unfazed by, or magically immune to, vibrant efforts to rethink how museums shaped by that past should evolve. My kids and I found it particularly mind-boggling after visiting the carefully curated exhibitions at the nearby New-York Historical Society. How did we get here in 2024?

Founded in 1869, with the support of wealthy philanthropists like Theodore Roosevelt Sr (father of US President Theodore Roosevelt) and JP Morgan, the museum sponsored major exploratory and hunting expeditions to Asia, Africa, and the North Pacific during the heyday of European and American colonialism. Scientific racism (the pseudoscientific belief that the human species can be divided into biologically distinct and hierarchically ranked racial groups) shaped the development of this museum, like many natural history museums established in the West during this period. Indeed, the museum’s devotion to scientific racism made it the site of the Second International Eugenics Congress in 1921. Among its most prominent leaders at that time was Madison Grant, a white supremacist eugenicist who helped block Asian immigration to the US and authored one of Hitler’s favourite books, The Passing of the Great Race (1916).

Grant was involved in displaying non-white humans in American zoos, and a whiff of the human zoo hits you viscerally as you move between the seemingly analogous halls of “Asian Peoples” and “Asian Mammals.” As many critics have noted, there’s no “Hall of European Peoples” because the museum was formed at a time when Western people thought of themselves as uniquely positioned at the top of a civilisational and racial hierarchy. They were not part of nature; they were its masters.

Also read: Should museums be woke? Europe’s war against ‘negativity’

Colonial mindset on display

It was deeply disturbing to see so many people milling about these displays, taking them in as if they could be taken seriously and were not the expired fantasies of another age. The placard introducing the “Hall of Asian Peoples” explains that this exhibit debuted in 1980. It’s clear something weird lies ahead from its vague assurance that “most Americans had more limited access to information on Asian cultures than they do today.” The placard adds that the museum recognises “the need to update” the displays, but there is no indication of when this will happen. Meanwhile, the hall is a sort of museum of a 1980s museum. The curator was (and evidently still is) an archaeologist who worked for US General Douglas MacArthur in Japan after World War II.

In fact, it’s doubtful Americans had limited access to information about Asia in 1980, given the extent of American involvement in the continent by then, including massive wars in Vietnam and Korea. However, the information that existed was certainly warped by orientalism, racism, and the military priorities that shaped its collection. The limiting of Asian migration until the 1965 Immigration Act also meant that in 1980 there were fewer Asian Americans to challenge racist depictions of Asians. But as an Asian American who was here in 1980, I can confirm that these views of Asians would have been controversial then too.

As you enter, a wall note explains the inaccuracy of anthropologists’ original assumptions about the simplicity of Asia’s “primitive cultures.” But rather than questioning the “primitive” label, it affirms that “understanding of primitive cultures” helps “grasp those of greater complexity.” The note adorns a room with dioramas of various cultures frozen in time, assuring that “time spent in this section will bring greater understanding of the higher [Asian] civilizations that lie beyond it.” It thus inserts the cultures depicted in the room into a sense of cultural hierarchy belonging to the colonial era.

Another room in the hall (presumably taking us further up the hierarchy) showcases a timeless “Indian village” marriage diorama. From its opening words, the placard emphasises the central role of caste in Indian society. Of course, caste is part of Indian life, but it is also a fetish of the colonial mindset, wielded to exoticise South Asians. Using the techniques of scientific racism to codify caste in a new way, British colonial administrators enshrined it ever more indelibly and rigidly in South Asian institutions; it is not the timelessly dominant essence of Indian culture. A depiction of the “Indian Cycle of Life” further suggests India is an exclusively Hindu society, with a single, heteronormative vision of life: From “infancy through…old age, Indians of both sexes carry on their role” towards furthering “family continuity,” a “total responsibility…summarized in the term dharma.”

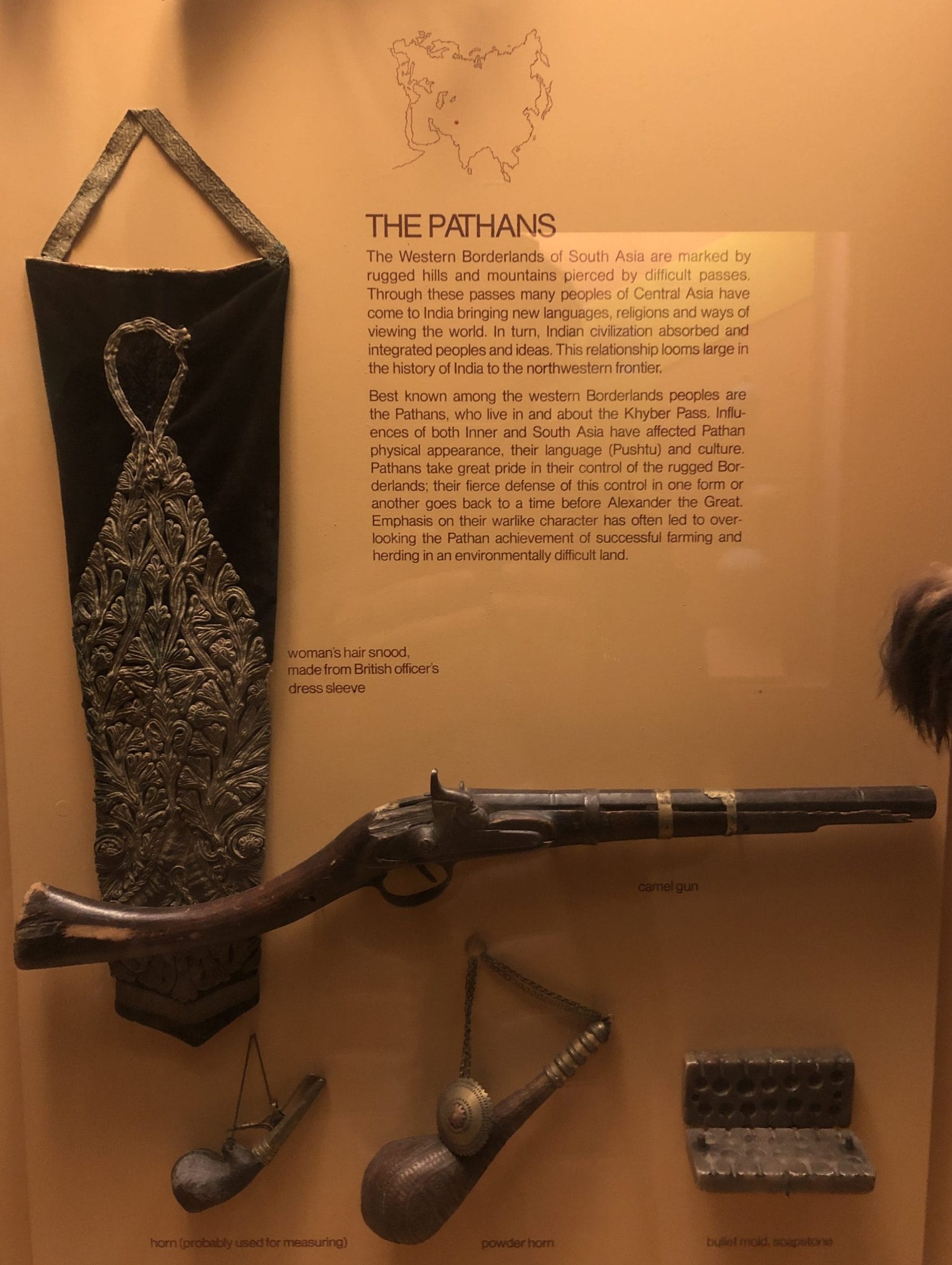

A nearby display on “The Pathans,” dominated by a camel gun and its accessories, explains that “emphasis on their warlike character has often led to overlooking” their farming and herding skill “in an environmentally difficult land.” Even in addressing the stereotype that has fuelled constant European and American aggression in the region now divided by Afghanistan and Pakistan, the placard reinscribes it, othering both Pathans and their environment.

Meanwhile, a diorama of Arab culture features a mannequin of a terrifyingly fierce Bedouin with dagger-like eyes, straight out of David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia. The Islam section includes gems such as the placard asserting “Islamic civilization arose primarily out of Arab respect for Greek and Roman accomplishments.” The entry/exit to this side of the gallery boasts a banner in orientalist font, “The Lure of Asia,” over a collage of orientalist motifs, dusty bazaars and minarets, genie lamps, and the like.

It might be a cover of Edward Said’s Orientalism, which in 1978, two years before the opening of this gallery, explained how the West defined itself against an Eastern Other, claiming a scholarly authority over “the Orient” that enabled political and economic domination of it. Loud strains of twangy music flow through this section. It’s Asian music but chosen and played to communicate exoticism, eroticism, and mystery—all the “allure” of the East that Said powerfully diagnosed. (I have since learned that the diorama of Isfahan, which I missed, includes a figure riding a magic carpet that has also inspired criticism.)

The neighbouring “Hall of African Peoples”, founded in 1968, was curated by another colonial-era British anthropologist. It, too, comes with a disclaimer about a need to update its dioramas of timeless African cultures, which employ outdated language about “Negroes.”

Also read: Why 43% of British still think colonial empire was a good thing, and a source of pride

Excuse of ‘rethinking updates’

It seems incredible that no one at the museum since 1980 up to the new leadership in 2023 has yet been able to update these galleries. Talking to staff, we got the impression that there was no active curatorial engagement with these displays and no sense of pressing need to change anything. Nor were staff able to share an effective way to reach out to the museum with concerns. This complacency and lack of reflection were troubling, and the displays disturbing enough, that I shared a thread on X (formerly Twitter) to raise awareness of these exhibitions in one of the US’s most important cities and to insist, publicly, as a historian, educator, Asian American, and mother, that the museum make outrageously overdue curatorial updates.

Many people who have visited the museum both recently and long ago validated our impression in response. One reported earlier consultations with Asian American communities that had had no effect. Several spoke as former employees of the museum who had found its stubborn refusal to change the offensive displays deeply disturbing. One shared that the resistance arose partly from a belief that the halls themselves were “historical artifacts.”

Certainly, a museum of old American mindsets has value in helping younger generations understand the even more intense racism experienced by earlier generations, and how hard-won change has been — but it needs to be presented as such. These exhibits came with a warning that they were outdated but did not disavow their objective of showcasing other societies; they have not morphed into an intentional effort to showcase how Americans once thought about other societies.

It’s not that we shouldn’t recognise and celebrate cultural differences; it’s that every culture should be recognised as dynamic, historically produced, and that certain ways of depicting Asians as utterly different, especially in their lack of dynamism, serve and have served violent and exploitative ends, including colonisation, aggressive wars, coercive labour, mass displacement, and more. The common-sense bottom line is that if visitors of Asian background don’t recognise themselves in these halls, and worse, find their culture insultingly misrepresented, the halls are doing something wrong. One South Asian-American commentator on X shared that as an “impressionable teenager,” visiting the museum had filled her with “shame and self hatred” about her roots.

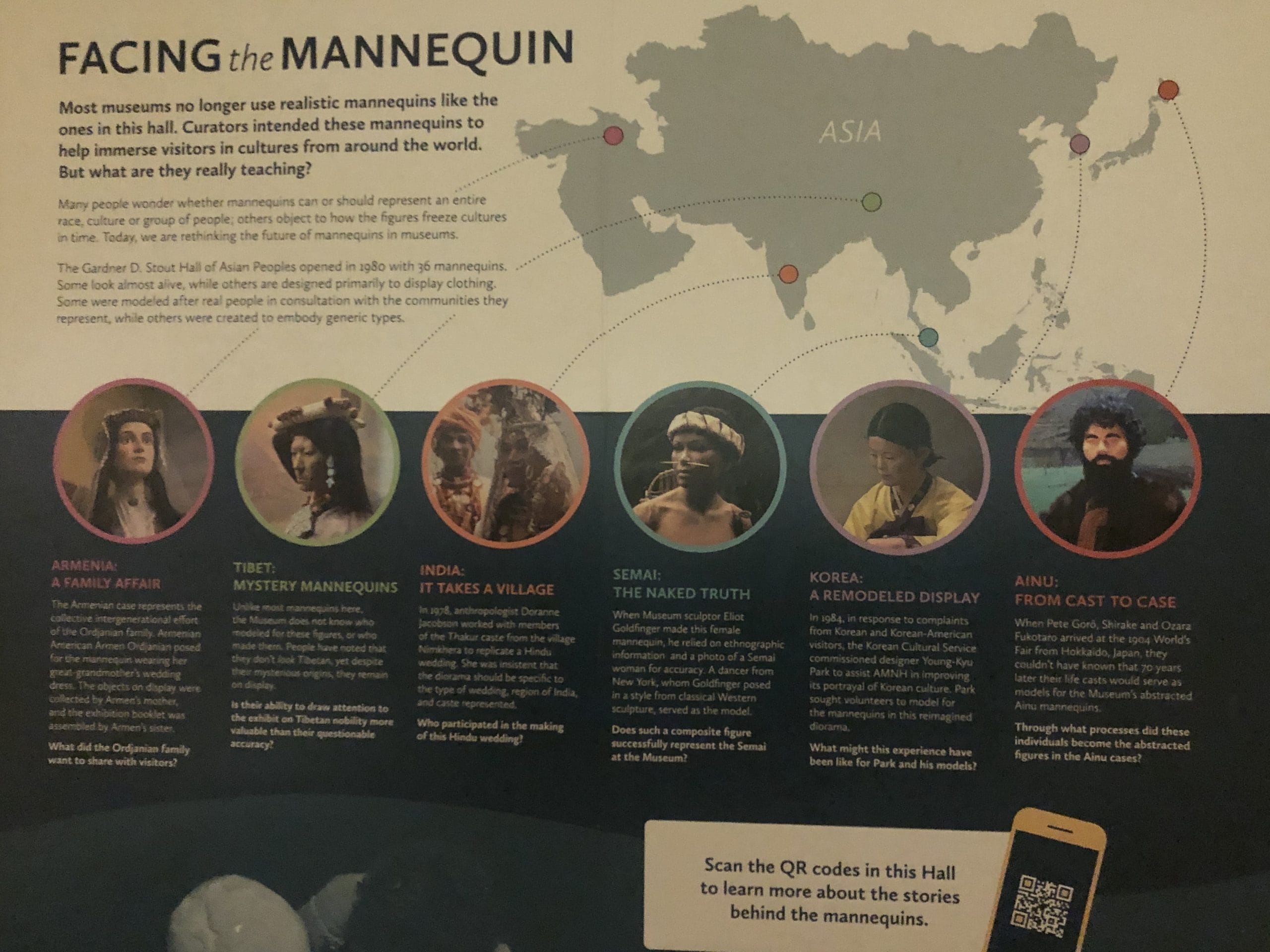

There does seem to have been one change: Deep within the labyrinthine gallery, you stumble on another evidently recent placard acknowledging that “most museums” no longer use mannequins because they “freeze cultures in time.” “We” too are “rethinking” them, it affirms. Is this placeholder promising rethinking now a permanent part of the gallery?

The slow correction of all this is especially baffling alongside one thoughtfully updated display in the museum’s main Theodore Roosevelt Memorial Hall. The glass case of a 1939 diorama depicting a 1660 encounter between Dutch and indigenous Lenape leaders now features captions carefully “reconsidering the scene” in light of its “stereotypical representations” and ignorance of the violence of colonialism. A placard acknowledges the “ongoing impact of colonialism” and the “urgent need to reconceive how diverse peoples and cultures are represented in the Museum.” Such singular reconsideration of one diorama, which the museum updated in 2018, creates the impression that the rest are somehow tolerable and fine.

Also read: The chaiwala-to-PM story is the stuff of museums. But the new Modi gallery fails to tap it

Longstanding demand for reform

The updates that have occurred resulted from outside pressure. For several years, starting in 2016, the American Museum of Natural History was where “museum controversy” was most heated in the US. Demonstrators regularly demanded change, targeting the museum’s fossilised 19th-century view “that Native Americans, Africans, Eskimos, and stuffed rhinos and tigers are all, in some manner, equally exotic and museum-worthy—while that which comes from Europe or white America, being civilized rather than “natural”, does not merit being displayed,” as American author-journalist Adam Hochschild wrote in The Atlantic in January 2020.

Protests also triggered the removal in 2022 of a statue outside the museum depicting Teddy Roosevelt on horseback, with unnamed black and indigenous figures in subjugated positions alongside him. The museum’s oldest gallery, depicting the cultures of the Pacific Northwest, was redone to great acclaim in 2022. Last year, the museum announced it would no longer display human remains (it has at different times displayed skulls, skeletons, mummified bodies, and artifacts made of human bones). However, it has yet to repatriate the thousands of human remains in its collections—collected as part of its historic investments in scientific racism. New federal regulations requiring museums to obtain consent from tribes before displaying cultural artifacts prompted an announcement earlier this year of the closure of two halls displaying indigenous objects.

In short, people have long been uncomfortable with the museum’s human cultures galleries, and changes have come, but not nearly as quickly and thoroughly as needed—and certainly not to the Asian displays. The museum’s role as a popular school trip destination, especially, has created deep attachment to the exhibits. But this is also the source of their ongoing harm: the everyday exposure they offer to dehumanising, colonial portrayals of non-white peoples. As one person who visited as a child shared on X, “these exhibits were our first exposure to many/all of these cultures and whether consciously or subconsciously, they remain the underpinnings of our knowledge of them.” The unchanged exhibitions are a liability for a well-loved museum, hurting visitors, damaging the museum’s reputation, and undermining education by spreading misinformation.

Indeed, the power of everyday exposure to racist depictions was evident in the responses to my thread telling me to go back to India and the quote-tweet, “In retrospect, ending suttee [sati] was a mistake.” But more than eye roll-inducing trolling, there is the barbaric reality of American war in Asia, hate crimes against Asian Americans, and genocide in Gaza—enabled by such portrayals.

Many responded to my thread reassuringly that the museum’s main draw is its scientific exhibitions—the fossils, insects, minerals, and planetarium. But devotion to science, if anything, puts more of an onus on the museum not to display inaccurate exhibits. People wander all its halls, trusting in their claims—why wouldn’t they, in a museum devoted to science and history, claiming scholarly authority?

Moreover, excellent exhibits of gems and minerals are poor compensation for the dehumanisation of non-white peoples. Tolerance for poor, and racist, humanistic learning in the name of prioritising science fuels the denigration of the humanities that leads to underfunded, and thus poor humanistic work, like these exhibits. In fact, the disparaging representations of other peoples have shaped the science collections, too. The museum’s reluctance to repatriate human remains may stem partly from fear of unleashing questions about the provenance of everything in its collections, including fossils and meteors looted from other parts of the world.

The museum is now under new leadership, and there is hope for change. In 2023, its endowment was roughly $700 million. That year saw the opening of the $431 million Gilder Center for Science, Education, and Innovation. The primary task of museums is curation. Pressure is needed to make clear to the museum the costs of inaction on the cultural halls and their perpetuation of a colonial mindset. There’s a strong case that until reforming them becomes a funding priority, their displays spreading misinformation and racial stereotypes should be shuttered to avoid causing further harm. As long as ticket prices are high, and these laughable galleries open, the American Museum of Natural History is a “tourist trap” (as a staff member at the New-York Historical Society described it.)

Public discussion of museums is part of the collective reeducation required after centuries of pernicious cultural dominance of these institutional artifacts of empire. This is how we educate ourselves about orientalism and racism and their real-world effects. This is how we make new history. Americans and people of Asian and African descent everywhere should demand, welcome, and support real change in the American Museum of Natural History—not just placeholders affirming the need for change.

Priya Satia is a history professor at Stanford University. She is the author, most recently, of Time’s Monster: How History Makes History. She tweets @PriyaSatia. Views are personal.

(Edited by Prashant)