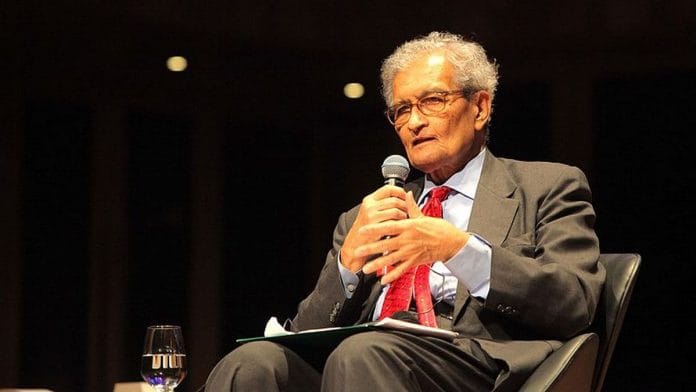

If public debates are a fine Indian tradition, Amartya Sen has been its foremost exponent. It is not just his contributions to welfare economics for which he got the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences in 1998. Sen has written books, given public lectures, and put forth compelling arguments on a wide array of topics ranging from myths and mathematics to Marx.

Last year, at an event at the Alipore Jail Museum in Kolkata, the 91-year-old polymath argued in favour of the concept of ‘Juktosadhana’ or the historical tradition of Hindus and Muslims living and working together harmoniously in India.

“It is not merely like allowing the other community to live and not beat up anybody. Perhaps that has become a necessity in the present situation as people are being beaten up. But most crucial is to work together,” Sen argued.

But when it came to Bangladesh, not just after the fall of the Sheikh Hasina regime last year, but since the last several years, Sen’s arguments have gone horribly off the mark.

In an interview with PTI on 2 March at his home in West Bengal’s Santiniketan, Sen said the current crisis in Bangladesh affects him deeply because he has “a strong Bengali sense of identity”.

He went on to say that Bangladesh has largely kept communal forces like the Jamaat-e-Islami in check, and should continue its “admirable commitment to secularism”. Sen also said his friend Muhammad Yunus, the chief adviser of Bangladesh’s interim government, is “taking significant steps but has a long road ahead to resolve the impasse”.

Sen could not have been more wrong.

Religious tensions and migration

While Sen has prescribed ‘Juktosadhana’ for India, his argument that Bangladesh has largely kept communal forces in check and should continue its “admirable commitment to secularism” is deeply flawed. The world has woken up to the plight of Bangladesh’s minority Hindus only after attacks on the community made global headlines, but Bangladesh’s experiments with secularism remained just that–experiments that did not yield desired results.

Political scientist Ayan Guha, a British Academy International Fellow at the University of Sussex, told ThePrint that since 1950, religious tensions in East Pakistan, and later Bangladesh, have caused steady exodus of Hindu refugees, mostly belonging to the lower caste Namasudra community. “Such migrations took place on the heels of major communal disturbances, with the largest exodus occurring during the Bangladesh Liberation War in 1970-71,” Guha said.

But even after the birth of Bangladesh, secularism remained a chimera as Hindus bore the brunt every time there was a political upheaval. Bangladesh President Mohammad Shahabuddin Chuppu told me in 2023 during an interview for my book, Being Hindu in Bangladesh, in Dhaka that he had headed a three-member judicial commission formed in 2006 to look into the 2001 anti-Hindu violence led by the Bangladesh Nationalist Party and the Bangladesh Jamaat-e-Islami after they came to power.

In 2006, Chuppu was a district and sessions judge. “I had travelled across Bangladesh to record the statements of Hindu victims of post-poll violence. I met Hindu women who have been raped so many times during that wave of anti-Hindu violence that they had lost their minds. I feel what happened in 2001 was even worse than what happened in 1971 during the Liberation War of Bangladesh,” he had said.

If Amartya Sen had followed the Bangladesh story down the decades, he would have known how the Hindu population in the country came down drastically owing to such attacks. And if he had paid heed to the words of Dhaka University professor Abul Barakat, who said in 2016 that there would be no Hindus left in Bangladesh in 30 years if the current rate of “exodus” continued, Sen would not have sung paeans to Bangladesh’s “admirable commitment to secularism”. Barkat had said that on an average, 632 people from the minority community leave the Muslim-majority country every day.

Historical sociologist Satanik Pal, who is a doctoral candidate at the National University of Singapore, told ThePrint that Sen is as Bhadralok as it gets and, like most of his ilk, he refuses to acknowledge Bangladesh’s losing battle with communalism while he remains critical of India.

This, Pal said, sets Sen apart from Dr. Bhim Rao Ambedkar who had the intellectual honesty to confront all forms of communalism head on and not fall prey to political correctness.

Also read: An open letter to Prof Muhammad Yunus

The Yunus conundrum

In his recent interview, while being “deeply affected by the current crisis in Bangladesh”, Sen heaped praises on Muhammad Yunus, and said he is “highly capable and a remarkable human being”. Sen also said Yunus was taking significant steps as head of the government. Yet, immediately after assuming power in August last year, the Yunus administration released Mufti Jashimu-ddin Rahmani, chief of the banned militant outfit Ansarullah Bangla Team.

Rahmani’s release alarmed Delhi as news reports said the Pakistan-based Lashkar-e-Taiba had partnered with the Ansarullah Bangla Team to carry out terrorist attacks in India’s Northeast. According to reports, Lashkar-e-Taiba’s collaboration with Ansarullah Bangla Team dates back to 2022, when they established a base in West Bengal with the aim of launching attacks in India.

It is not just Rahmani’s release that has alarmed Bangladesh watchers since Yunus took over as the chief advisor to the interim government. A Nikkei Asia report, dated 19 March, said a resurgence among Islamist groups is raising serious concerns in Bangladesh as its interim government struggles to manage a deteriorating law-and-order situation with murder, rape, and other crimes on the rise.

The report said that in post-Hasina Bangladesh, cases of moral policing and harassment of women by hardline religious mobs are becoming a feature of public life. “People are being called out for eating during the holy month of Ramadan, restaurants have been vandalized for staying open during daylight fasting hours while women are harassed for not wearing headscarves.”

Dhaka-based journalist Sahidul Hasan Khokon does not see the rise of radicalism in Bangladesh as Yunus’s failure. Instead, he told ThePrint, all radical groups, including the Bangladesh Jamaat-e-Islami, have been emboldened deliberately by the Yunus administration.

“Yunus wants to hold on to power by letting radical groups run the streets. Where was the police when Sheikh Mujib’s house, 32 Dhanmondi, was brought down? Don’t forget Yunus had lifted the ban on Jamaat immediately after coming to power,” Khokon said.

Along with Bangladesh’s record on secularism, Sen may also want to re-evaluate and engage in more critical arguments about his good friend’s “significant steps” in trying to revive Bangladesh. Because as Sen himself writes in his 2005 book The Argumentative Indian: “Discussions and arguments are critically important for democracy and public reasoning. They are central to the practice of secularism and for even-handed treatment of adherents of different religious faiths.”

Deep Halder is an author and a contributing editor at ThePrint. He tweets @deepscribble. Views are personal.

(Edited by Aamaan Alam Khan)

Academics like Amartya’s ego blinds them as much as the fundamentalists. The only difference is that Amartya enjoys an elite network that cushions his privilege of intellectual dishonesty.

When an economist chooses leftism over free market, that means he learnt wrong economics. So such persons usually do wrong things.

Amartya Is not Sane

This has been a chronic ailment of the “left leaning” liberal intelligentsia. Conflating certain strains of Islamic orthodoxy with a proto-communist egalitarian society and living in perpetual fear of being branded “Islamophobic” has turned them blind to the grave portents of radicalism. While no rebuke can be harsh enough for Hindu irredentism, Mr Sen and his ilk is loathe to do anything but mollycoddle Islamist fundamentalist. This blindspot renders them ineffectual in Bangladesh and the mendacity renders them vulnerable to charges of hypocrisy in India. If the left is regain any semblance of moral authority, they need to call a spade a spade irrespective of the faith it claims to profess.