A towering Chinese porcelain pillar of six vases has come to India. It is both aesthetic and political. It contains images and stories of strife, oppression and the hot-button issue of anti-migrant politics in the Western world and, to some extent, India.

Exiled Chinese dissident artist Ai Weiwei is intensely and unapologetically political. By upending and re-imagining traditional and historical cultural motifs, his subversive art offers a scathing commentary on the current state of the world. Ai Weiwei opened his first solo exhibition in India last week at the capital’s Nature Morte art gallery, featuring artworks from the past two decades.

More than a dozen artworks are on display and they summarise all the reasons why he is one of the most controversial and provocative contemporary artists in the world.

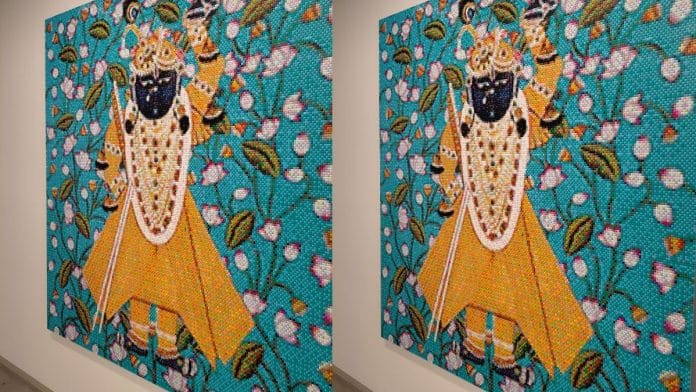

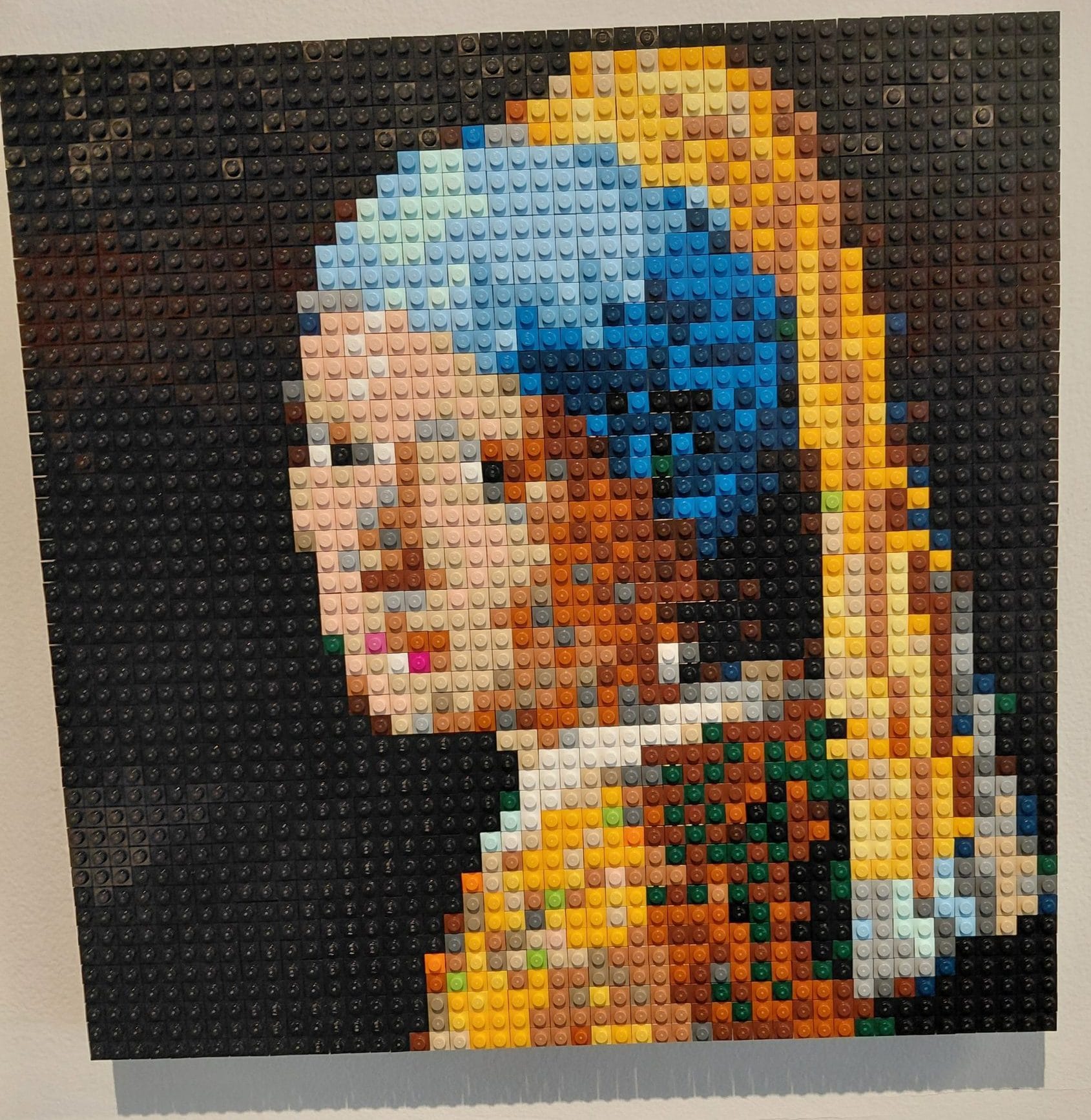

First are his Lego artworks.

Ai Weiwei’s signature Lego-built reinventions of famous legacy paintings are in the exhibition — the famous 17th-century Girl with a Pearl Earring and Monet’s Water Lilies composed of tens of thousands of LEGO and WOMA toy bricks. For Indian audiences, he has created two new Lego artworks – one is a giant Pichwai artwork of Krishna’s child figure, and the other is a V.S. Gaitonde painting. There is also a Lego Mona Lisa smeared with cream – a reference to the cake that was thrown at the glass covering of the painting as a climate protest in 2022.

His plastic toy brick recreations are a commentary on art, mass production, elitism and the idea of the authentic.

A clay pot with the hand-painted Coca Cola logo merges history with pop imagery, capitalism and propaganda.

Another wall installation uses stretchers from World War II with antique buttons stitched on them showing the four-letter word. It is a stunning anti-war statement.

Also read: Mahishasura Mardini in Ghazni: Humayun’s Tomb museum exhibition offers unsafe truths

Porcelain politics

The real blockbuster installation in the exhibition is called “Porcelain Pillar with Refugee Motif” that he made in 2015.

Ai Weiwei paints the six blue-and-white Chinese porcelain vases stacked together as a pillar with a narrative that is on the edge of contemporary politics and the turbulent world. Refugees packing everything they have into little suitcases and cloth bundles; a Muslim woman holding an infant; a man with a crutch walking long distances in the rain; a young male refugee drowning in the sea; another swimming through the perilous waves with an infant in his arms; refugees living in tented camps upon arrival; stone-throwing masked Palestinians being shot at against the backdrop of barbed wire; and a war tank rolling down men.

All these are haunting motifs that define the trauma of the refugee experience — war, ruins, journey and crossing the sea, refugee camps and demonstrations. The pillar stands like a totem pole of global political conflicts that create the conditions for persecution and refugee flight. And the fragile porcelain only exemplifies the refugee story.

Also read: Should museums be woke? Europe’s war against ‘negativity’

Ai Weiwei and the global refugee crisis

Ai’s work with the international refugee crisis began over a decade ago. He observed the flood of refugees who poured into Europe, researched and worked with relief camps as the boats began coming in filled with migrants into the Greek island of Lesvos. He set up a studio on the island and collected objects for his art installations.

During this time, in 2016, I did a story on him for my former employer The Washington Post. It was about a controversial art project that Ai Weiwei collaborated on with Indian artist Rohit Chawla to spotlight the art world’s attention on the refugee crisis in Europe. He closed his eyes and lay face down on a cold, pebbled beach, imitating the iconic image showing the lifeless body of the three-year old Syrian toddler Aylan Kurdi, who had drowned in the Mediterranean Sea, I wrote. It was published by The Washington Post and India Today magazine. That photograph was exhibited at the India Art Fair in New Delhi that year.

“Bringing Ai’s work to India isn’t about creating a spectacle — for us, it is about urgency. His work speaks to the present moment with total clarity: history, power, borders, memory. India is a place where these questions are lived, not abstract, and this exhibition invites that conversation without flinching,” said Aparajita Jain, co-director, Nature Morte.

Rama Lakshmi, a museologist and oral historian, is ThePrint’s Opinion and Ground Reports Editor. After working with the Smithsonian Institution and the Missouri History Museum, she set up the ‘Remember Bhopal Museum’ commemorating the Bhopal gas tragedy. She did her graduate program in museum studies and African American civil rights movement at University of Missouri, St Louis. Views are personal.

(Edited by Prashant Dixit)