This year marks a decade of the Commercial Courts Act, 2015. As the name suggests, the Act was enacted to reduce delays in resolving commercial disputes in India. It carved out contract-related suits into a separate category called “commercial suits” and empowered state governments to set up dedicated divisions (benches) in high courts and district courts for resolving commercial suits.

Non-commercial suits, such as defamation and family partitions, were retained as “ordinary suits” and were not covered under the Act. The expectation was that such segregation between commercial and ordinary suits, and the creation of dedicated benches to resolve the former, would expedite the disposal of high-value commercial suits across states in India. A decade later, it is time to ask: Has the law delivered on its promise?

In this article, using data on cases filed from the Bombay High Court, we find that the Act has not delivered on its purpose of expediting the disposal of commercial disputes. We offer some explanations for why this might be the case.

A pre-2015 baseline

India’s global reputation for poor contract enforcement has been repeatedly documented by scholars, policymakers and commentators. In 2014, the now-discontinued World Bank’s annual Ease of Doing Business survey ranked India at 186 out of 189 countries in the category of “Enforcing Contracts”. The report, based on anecdotal surveys of experts, suggested that it took about 1,420 days to enforce a contract in Mumbai and Delhi. Perhaps more reliably, the report of the 253rd Law Commission of India, using the data on suits pending before five high courts, found that 75 per cent of the suits were pending for more than two years, and more than a quarter were pending for more than ten years.

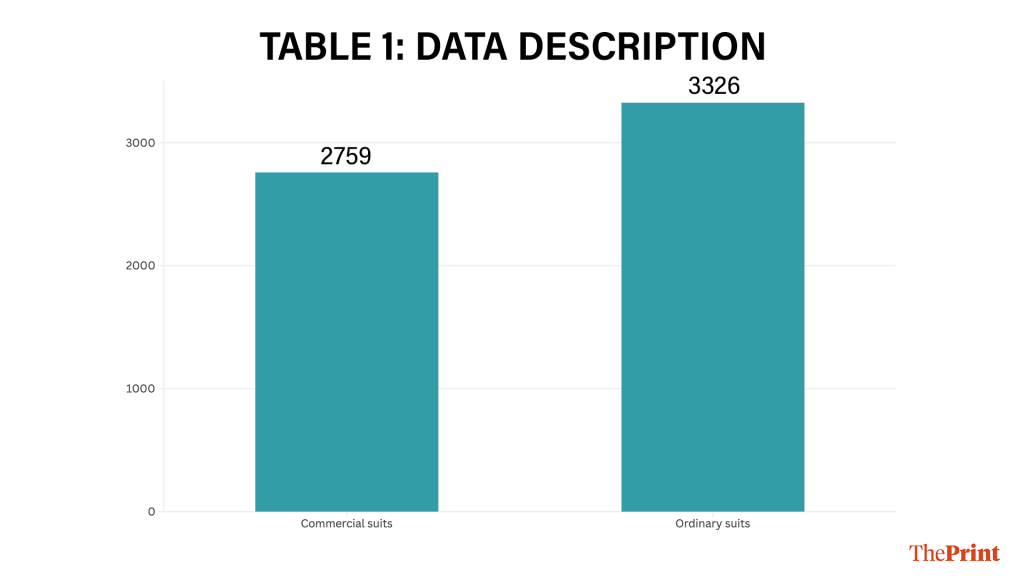

The question before us, therefore, is whether the Commercial Courts Act has moved the needle on the above baseline. We collect the lifecycle data of all commercial suits that were filed before the Bombay High Court in eight years, between 2017 and 2024. We then compare it to the lifecycles of ordinary suits that were filed before the Bombay High Court, which are not covered by the Act, during the same period. Table 1 shows the number of cases used for our analysis.

The question before us, therefore, is whether the Commercial Courts Act has moved the needle on the above baseline. We collect the lifecycle data of all commercial suits that were filed before the Bombay High Court in eight years, between 2017 and 2024. We then compare it to the lifecycles of ordinary suits that were filed before the Bombay High Court, which are not covered by the Act, during the same period. Table 1 shows the number of cases used for our analysis.

Also read: Hindu temples belong to deities & devotees, not the govt. Himachal Pradesh HC got it right

Impact on speed of disposal

We find that the duration of cases has not moved in a decade. The median time taken to dispose of such cases is 1,580 days. In fact, if we use the World Bank-reported median of 1,420 days for enforcing contracts as a reliable baseline, the disposal time for commercial suits has increased marginally. Strikingly, with a median disposal time of 1,117 days, ordinary suits seem to be getting disposed of faster, by more than a year, compared to commercial suits.

While widely used as a proxy for measuring the performance of courts in India, the median time for the disposal of cases is, in fact, a misleading metric for assessing the timeliness of courts. This is because the median time for case disposal only records the time that disposed off cases took, but does not account for the cases that continue to remain pending in the system. An accurate metric must account for how long pending cases have been in the system. In other words, a more accurate measure is the proportion of commercial suits that continue to remain in the system without getting disposed of.

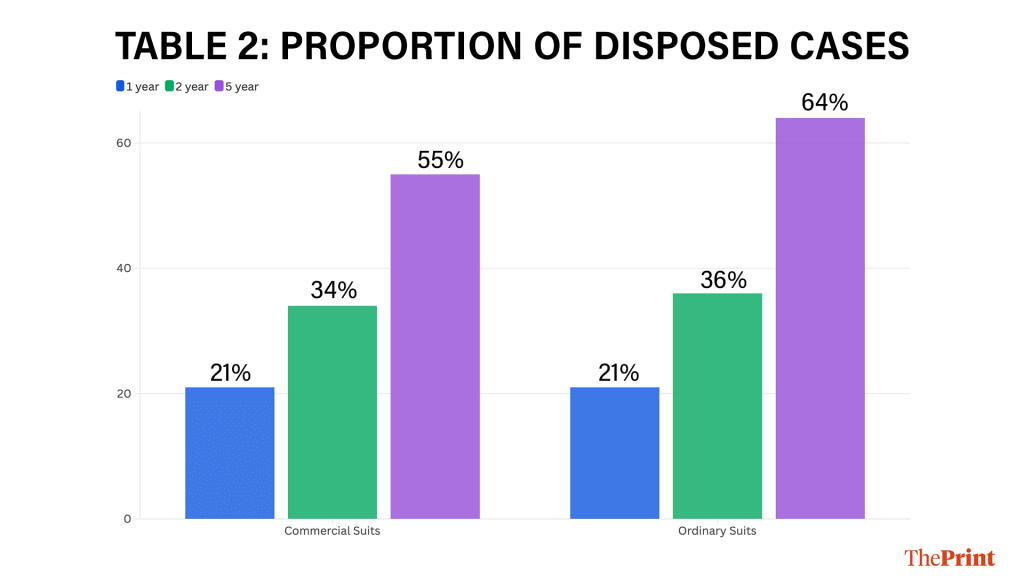

Table 2 shows the proportion of commercial and ordinary suits disposed of within one, two and five years, respectively. The Table suggests that commercial suits take about the same time as ordinary suits to get resolved in court. Thus, more than 60 per cent of the suits remain pending after two years of having been filed, and this proportion is agnostic to whether the suit is a commercial or ordinary suit. At the five-year mark, a greater proportion of commercial suits remain pending compared to ordinary suits.

Finally, the Commercial Courts Act prescribes several procedures and staged timelines to fast-track case disposal. For instance, it mandates the court to hold a case management hearing within four weeks of filing of affidavit of admission or denial of documents by all the parties. Further, it prescribes that cases must be completed within six months of such a case management hearing. However, our data shows that in 40 per cent of commercial cases, not a single hearing was conducted for three months after the filing date of the case, and for 25 per cent of cases, this extended to six months.

Finally, the Commercial Courts Act prescribes several procedures and staged timelines to fast-track case disposal. For instance, it mandates the court to hold a case management hearing within four weeks of filing of affidavit of admission or denial of documents by all the parties. Further, it prescribes that cases must be completed within six months of such a case management hearing. However, our data shows that in 40 per cent of commercial cases, not a single hearing was conducted for three months after the filing date of the case, and for 25 per cent of cases, this extended to six months.

Also read: Supreme Court’s nod to green cracker is headache for Delhi agencies. Implementation is key

Possible explanations

The sub-optimal performance of the Commercial Courts is not attributable to the lack of rules, but a failure of enforcement and capacity, creating a litigation culture that undermines both the efficiency and the predictability of cases.

First, we, in India, are way too familiar with the story of endless adjournments. The Code of Civil Procedure (CPC), which is the procedural code for the conduct of civil suits, prescribes a maximum of three adjournments to expedite trials. Earlier research shows that despite this mandate, excessive adjournments remain the norm, and nearly 50 per cent of hearings conducted by the Bombay High Court’s commercial courts are adjournments. The problem is not so much the adjournments themselves, but the absence of consequences for the parties or lawyers who seek them. A common practice of linking litigation fees to the number of hearings, the absence of any incentive, such as a success fee linked to good case outcomes, and the near absence of costs and penalties for seeking unnecessary adjournments, creates a litigation culture of laxity and unwarranted delays.

Second, the purpose of creating a subject matter-specific special court or bench has two benefits: funnelling commercial cases through a dedicated channel and the efficiency gains from judicial specialisation. However, an analysis of randomly selected sitting lists of the judges of the Bombay High Court shows that the matters assigned to judges presiding over the commercial division are not restricted to commercial disputes. These judges also hear writ petitions, testamentary matters, adoption, custody and guardianship matters, and matters arising out of the Guardians and Wards Act and the Juvenile Justice Act.

The Commercial Courts Act shows that the enactment of laws, by itself, does not create performance, systematic measurement, and incentives do. Efficiency cannot be legislated; rather, it must be built through feedback and accountability. Reform must begin with knowing the baseline, tracking outcomes, and redesigning institutions when the needle does not move.

Bhargavi Zaveri-Shah is the Co-founder and CEO of The Professeer. She tweets at @bhargavizaveri.

Pavithra Manivannan is a Research Lead at XKDR Forum. She tweets at @PavithraM_.

Views are personal.

(Edited by Saptak Datta)