On March 10, Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), a start-up focussed lender, became the largest bank to fail in the US since the 2008 global financial crisis. The bank’s collapse was triggered by a downturn in the technology sector and the Federal Reserve’s aggressive monetary policy tightening to tame record high inflation.

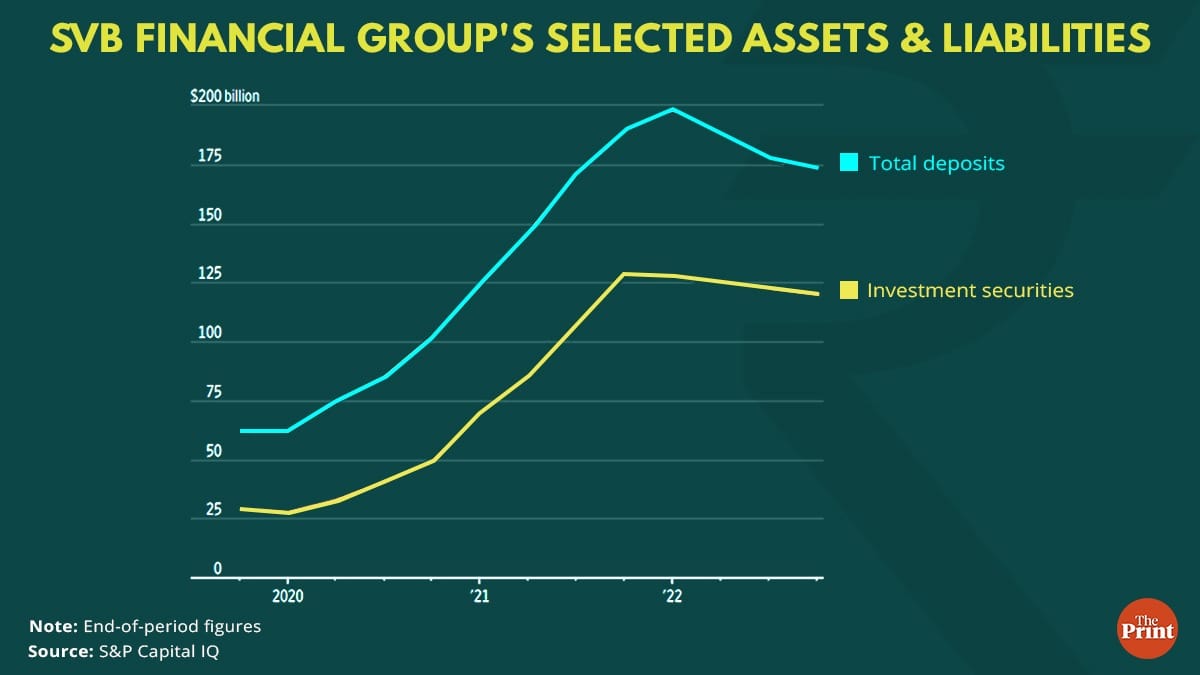

The bank had seen a huge influx of deposits from start-ups and venture capital firms during the pandemic. It invested the deposit money in long-term US government securities. These investments are typically safe but the value of these investments fell due to the current high interest environment — the US Federal Reserve has increased the interest rate by a massive 450 basis points.

The depositor base of SVB was largely the start-ups and other-technology focussed companies. Due to the drying up of venture capital funding through public offerings, these companies were scrambling for funds, leading them to tap into their deposits. The resulting large-scale withdrawal of deposits required SVB to sell their bond holdings. So, when the bank started selling bonds, it suffered mark-to-market losses as the prices of existing bonds dropped with the increase in yields.

The bank’s chief executive officer sent a letter to shareholders that it has suffered a loss of $1.8 billion on the sale of US treasury bonds worth $21 billion and outlined a plan to raise additional capital through share sale.

The letter sparked a run as the venture capital firms started to pull their money. Since these were corporate deposits, they exceeded the deposit insurance limit of $250,000. The run amounting to $42 billion — a quarter of the bank’s total deposits in a day — made it incapable of honouring its obligations. It ran out of cash.

Also read: Real estate over banks — where the average Indian household is putting its savings

Prompt regulatory interventions

The SVB’s insolvency was followed by prompt regulatory interventions involving coordination between the Treasury Secretary, the banking regulator and the resolution authority. The bank was closed by the California banking regulator and placed under the receivership of Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC).

The FDIC seized the assets of the bank, created a bridge bank called the Deposit Insurance National Bank of Santa Clara and transferred all insured deposits of SVB to the bridge bank — an entity to temporarily take over the liabilities and operations of a failed bank till a buyer is found. The bridge bank, in this case, will ensure continuity of all banking activities. All insured depositors have access to their insured deposits. The uninsured depositors will receive their payouts as the FDIC sells the assets of the SVB.

To prevent the run on banks and meet the demands of depositors, the US Fed has set up an additional funding facility for banks called the Bank Term Funding Program. Under this facility, loans of up to one year will be provided to banks and other depository institutions through pledge of government securities at par, eliminating the need to quickly sell securities in times of stress.

Need for counter-cyclical tools

The collapse of the Silicon Valley Bank underscores the need to have adequate countercyclical macroprudential tools in place to provide a buffer against losses on account of rising interest rates.

One such tool in the context of Indian banking regulation is the Investment Fluctuation Reserve (IFR). This reserve is created by transferring the gains realised on sale of investments during an easing interest rate cycle. These gains act as shock absorbers during an interest rate tightening phase.

To address the impact of sharp increase in the yields on government securities, the rules governing the IFR were refined in 2018. According to the revised rules, banks are required to transfer profits on sale of investments to the IFR until the amount of IFR is at least 2 per cent of the portfolio of government bonds available for trading and sale.

According to the Financial Stability Report, December 2022, the banking system’s IFR reached 2.2 per cent of the portfolio of securities available for trading and sale in March 2022. This helped banks tide over losses in the first quarter of 2022-23.

Indian banks are better placed to address SVB-like crisis

According to an analysis by global financial major Jefferies, Indian banks are not particularly at a risk of facing an SVB-like crisis. Unlike the concentration of deposits of SVB, 60 per cent of deposits of banks are held by households. These are sticky in nature as households do not move quickly to other investment options such as government securities. On the asset side, 60 per cent are held in the form of loans and investments constitute 25 per cent of the assets.

Recently, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) enhanced the limit for securities that are held to maturity (HTM) to 23 per cent of deposits. Under HTM, the bonds are exempt from being marked to market and hence banks can avoid treasury losses. The other two bond portfolios — the available for sale (AFS) and held-for-trading (HFT) — are subject to losses in the event of rise in the bond yields.

Time to bring Resolution Corporation back on the agenda of financial sector reforms

An important lesson emerging from the SVB crisis is the need for a prompt resolution framework so that the depositors do not have to face a moratorium on their deposits. While the crisis raises questions on the role of banking regulation and supervision, the regulators made swift interventions and ensured that depositors would be protected without a tax-payer funded bailout. The FDIC has taken over the bank to ensure a prompt market-based resolution.

In India, too, there is a need for a resolution law and a framework for resolution of banks. The legal framework should provide for oversight of the bank by the RBI and a Resolution Corporation.

The Resolution Corporation should have the authority to monitor risks and intervene early and resolve through the globally-recognised resolution tools such as sale of business and bridge institutions.

Burden should not be borne by the tax payers directly or indirectly. If SBI or LIC step in to buy shares in a troubled bank, their losses are covered by the taxpayer.

The Financial Resolution and Deposit Insurance (FRDI) Bill providing for establishing a resolution authority, which would have powers to undertake prompt resolution for banks was introduced in the Lok Sabha in 2017 but was later withdrawn due to stiff opposition on some provisions. Time is perhaps right to initiate steps to re-introduce the bill after taking the concerns on-board.

Radhika Pandey is Senior Fellow at National Institute of Public Finance and Policy.

Views are personal.

Also read: How did Indian economy perform during pandemic & after? Turns out, not as badly as was estimated