Last week, the government approved the Unified Pension Scheme (UPS) for government employees, which tries to strike a middle ground between reverting to guaranteed pension and trying to stick to the path of fiscal discipline.

The UPS, which will be implemented from 1 April, 2025, provides certainty to pensioners by guaranteeing 50 percent of their average drawn basic pay in the last 12 months before retirement as pension. This has been done while retaining the contributory nature of pension, wherein employees contribute to their pension from the salary they receive while in service.

Recently, several states, such as Rajasthan, Punjab, Himachal Pradesh, Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand, reverted to the Old Pension Scheme (OPS). OPS is non-contributory and fully funded by the government.

While the announcement of the UPS seems to be a counter to the Opposition’s promise of a return to OPS, the fiscal implication of the move is unclear. The government would have to raise its budgetary allocation on pension to address the potential shortfall in contributions towards assuring a guaranteed pension.

Pension reforms

The pension plans of governments are primarily classified as defined benefit and defined contribution plan. In the defined benefit plan, pension is guaranteed from the revenue of the governments. The benefits are defined based on the employee’s final or average salary.

In India, the pension scheme in the pre-2004 period (OPS) was based on defined benefit plan.

In the late nineties, there was a growing recognition that rising financial burden of defined benefit schemes would jeopardise the fiscal health of governments. This was particularly worrisome in the light of the changing demographic profile. There was also a concern that the defined benefit pension scheme was inequitable as it provided disproportionate benefits to civil servants, while the bulk of the population was devoid of any old age income security.

As a culmination of the growing concerns around the unsustainable pension liabilities, the Indian government set up an expert committee named Old Age Social and Income Security project (OASIS), to deliberate on a sound pension system design. This brought together experts and academics, who designed the New Pension System (NPS). The committee submitted its report to the Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment in January 2000.

NPS was based on the principles of self-help and thrift, instead of the notion that the state is responsible for payment of pension benefits for life. It is a defined contribution-based pension plan under which contributions by the employee are matched by equal contributions by the government or the employer. The pension benefits depend upon the market performance of the pension fund and the government’s fiscal cost is limited to a pre-specified rate of contribution.

All new recruits to civil services from 1 January, 2004 were placed into the NPS. By making the civil servants the early adopters of the system, foundations were laid for a framework, where the bureaucracy had the incentive to make the NPS work well so that it could be used by the larger population. NPS was extended to all citizens on 1 May, 2009.

Also Read: Production, demand, non-food credit grew moderately in Q1. GDP report card likely to be a mixed bag

Fiscal burden of UPS

In recent years, some states have reverted to the old pension system. As the clamour for a guaranteed pension gained traction, the government set up a committee in March 2023 to look into the issues and suggest a way forward.

The UPS, which incorporates some of the features of the old and the new pension system, is the brainchild of the committee. While it seems fiscally prudent as compared to the old pension scheme, it has rolled back some of the desirable features of NPS, and will entail an additional cost on the exchequer.

To finance the guaranteed pension, the government will now contribute 18.5 percent of the basic salary of employees, up from 14 per cent. Since the guaranteed pension will be indexed to inflation, the government will also have to cover the inflation risk.

The government has projected an additional expenditure of Rs 6,250 crore in the first year and Rs 800 crore towards arrears. In any case, each year, the government would have to cover the shortfall towards assuring a guaranteed pension, which would require additional budgetary allocations.

Currently, the pension outgo of the government consists of pension payments to subscribers of OPS, and pension contribution (currently 14 percent) of employees covered under NPS. The benefits of NPS would accrue, when the employees under NPS begin to retire.

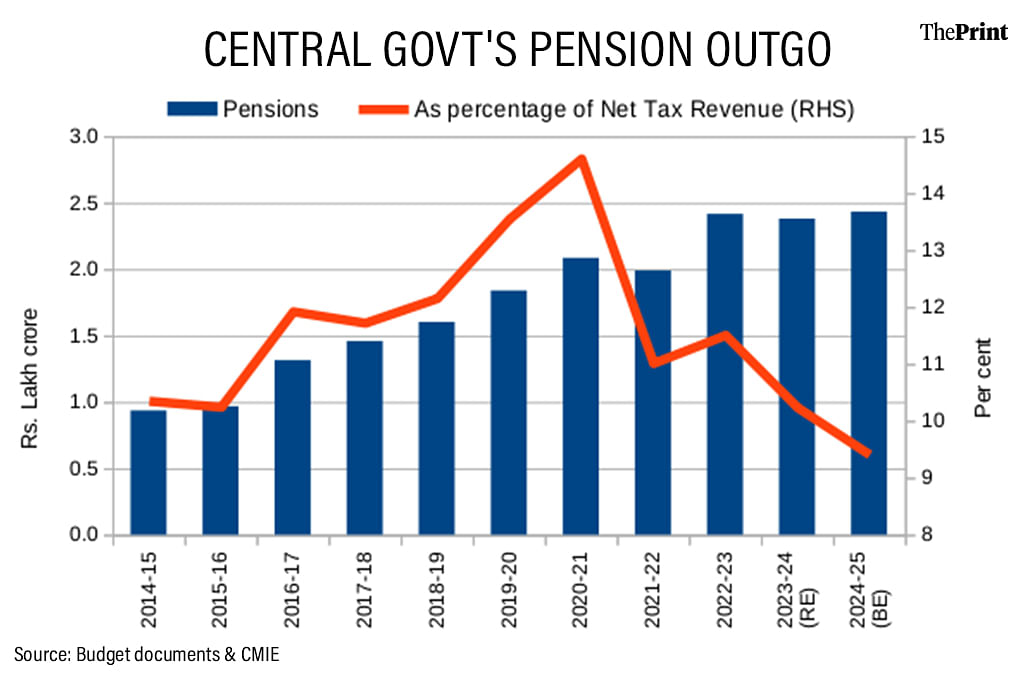

Pension outlay constitutes a significant proportion of the budget of the central and state governments. For the central government, the outlay on pensions is almost 10 percent of the net tax revenue. This will see an uptick with the rollout of the guaranteed pension.

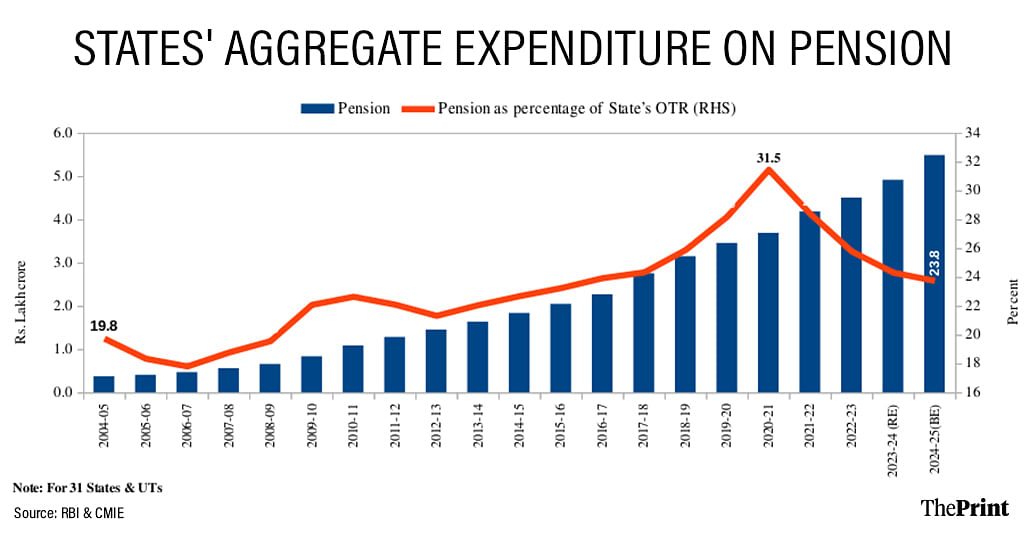

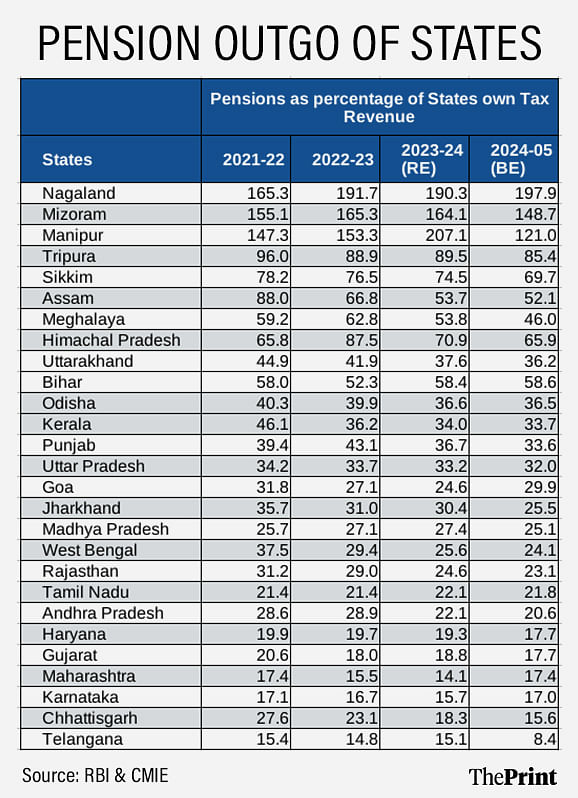

For states, the overall yearly pension outlay has risen to Rs 5 lakh crore. At the disaggregated level, there exists significant variation in pension outlay of states. In addition to the north-eastern and hilly states, the pension outlay exceeds one-third of the own tax revenues in states, like Bihar, Assam, Odisha, Kerala and Punjab.

A recent study by the Reserve Bank of India shows that the switch to OPS will increase the pension burden by 4.5 times of the estimated expenditure under NPS.

Going forward, the trajectory of the pension burden of states will depend on the choices they make with regards to the design of the pension scheme.

A return to guaranteed pensions runs the risk of fiscal uncertainty. This uncertainty stems from the lack of clarity on the operational details. The actuarial assumptions and the investing pattern of the funds will shape the outlay on the scheme. If the additional contribution is invested in safer assets, the upside will be limited and the outlay will increase. The enhanced spending on pension will likely limit the space for spending on productive avenues.

The UPS has also reversed one of the most appealing features of NPS—its equitable coverage.

Radhika Pandey is associate professor and Rachna Sharma is a fellow at National Institute of Public Finance and Policy (NIPFP). Views are personal.

Also Read: India enjoys healthy trade surplus with Bangladesh. The political crisis can hurt trade, FTA chances