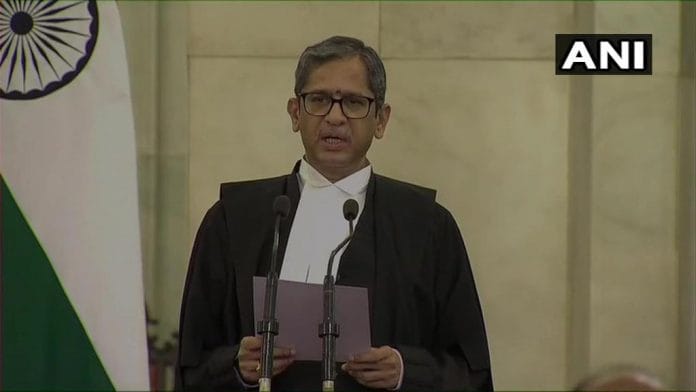

New Delhi: Before he took oath as the country’s 48th Chief Justice of India, Justice N.V. Ramana received blessings from the archakas (priests) of the Tirumala Tirupati Devasthanam and the Srisaila Devasthanam at his residence Saturday morning.

Moments after the brief ceremony got over, the new CJI headed to his office in the Supreme Court to preside over an urgent meeting with a few senior judges to discuss and work out the logistics of court functioning in view of Covid-19.

“In the last few days, judges as well as the court staff have got indisposed due to someone in their respective families falling ill due to Covid,” a source told ThePrint. “The court work cannot stop, therefore, the new CJI called the meeting to work out a protocol to be followed.”

The meeting was attended by Justices R.F. Nariman, U.U. Lalit, A.M. Khanwilkar, D.Y. Chandrachud, Ashok Bhushan and L.N. Rao.

For Justice Ramana, to keep the court functioning during the present unprecedented crisis is among the many challenges he faces as the new CJI.

A “God-fearing” person, according to those who know him, Justice Ramana has always maintained a calm and composed demeanour during court hearings, only speaking through his judgments and is credited with delivering some landmark verdicts underscoring constitutional values and principles of natural justice.

In October last year, he came under attack from Andhra Pradesh Chief Minister Y.S. Jaganmohan Reddy who publicly accused Justice Ramana of influencing judges of the state High Court to deliver verdicts against his government.

An in-house inquiry gave a clean chit to Justice Ramana on 24 March, following which the then CJI SA Bodbe went on to designate him as his successor.

Speaking to ThePrint on Justice Ramana’s appointment, Sneha Kalita, a Supreme Court lawyer, said: “At this crisis time we are looking for a CJI who is not only a man of his principles, but also with imbibed humility. And also I am very sure that under his mentorship, he would definitely bring gender parity in our judicial system.”

Also read: Goswami hearing to Prashant Bhushan contempt case, Bobde’s CJI stint wasn’t without controversy

Student leader, journalist to CJI

Born to a family of farmers at Ponnavaram village in Andhra Pradesh’s Krishna district, Justice Ramana was a student leader, a journalist and a lawyer before his stint as a judge.

His tenure as the CJI will last right until 25 August 2022.

As a student leader Justice Ramana fought for civil liberties during Emergency and also lost an academic year. Recounting his experiences of those times, the judge at a book launch event sometime back said he had “no regrets as he had seen many youngsters sacrificing their lives to protect human rights”.

Before he enrolled as an advocate in 1983, Justice Ramana dabbled as a journalist. He worked with Eenadu newspaper from 1979 to 1980 and reported on political and legal matters for the newspaper.

As an advocate he specialised in constitutional, criminal, service, and inter-state river laws at the Andhra Pradesh High Court.

Appointed as a permanent judge of the state high court in 2000, Justice Ramana was appointed the Chief Justice of the Delhi High Court in 2013 and a year later, was elevated as a judge of the Supreme Court.

Controversy over Justice Ramana’s elevation

The judge’s elevation came under a shadow when a petition was filed against his appointment as a HC judge. The two petitioners contended before the Supreme Court that Justice Ramana was a proclaimed offender in a rioting case and that he hid this fact when he enrolled himself as a lawyer in 1983.

The case pertained to large-scale rioting in which several students of Nagarjuna University in Guntur, including the judge, allegedly damaged public property, including transport and buses.

Interestingly, the petitioners in the case were represented by senior advocate, the late Ram Jethmalani, at whose instance Justice Ramana’s appointment was made.

When this fact was brought to Ram Jethmalani’s notice, the latter wondered what he should do. At the court’s suggestion, the senior lawyer withdrew from the case.

In February 2013 the petition was dismissed with a cost of Rs 50,000 on the petitioners.

Also read: Using AI tools in judicial process can improve justice delivery, but amplify biases: Report

Conventional judge who adheres to principle of judicial discipline

Justice Ramana has been part of several landmark judgments, some of which he has authored himself. They reflect his adherence to judicial discipline and the rule of precedent.

Deciding a batch of petitions against internet restrictions in the UT of Jammu and Kashmir, a bench led by him ruled that access to the internet is a fundamental right. It pulled up the government for the telecommunications blackout after the semi-autonomous status of the region was nullified.

He was also part of a bench that brought the CJI’s office under the Right to Information Act. Another bench led by Justice Ramana fast-tracked cases pending against MPs and MLAs, a judgment that was perceived by many as a reason for Reddy’s outrage.

The judge also delivered verdicts in several politically-sensitive cases including the one related to the Karnataka assembly in 2019 where it was clarified that disqualification under the Tenth Schedule (anti-defection law) for defection could not operate as a bar for contesting elections again.

In the case of Maharashtra, the judge had ordered an immediate floor test in the state assembly to prevent horse-trading in 2019.

And in a judgment that put the spotlight on gender inequality when it came to insurance-claim cases, the judge ordered fixing a notional income for non-earning homemakers in such matters.

“The sheer amount of time and effort that is dedicated to household work by individuals, who are more likely to be women than men, is not surprising when one considers the plethora of activities a homemaker undertakes,” he had said in the verdict.

Challenges facing the new CJI

Justice Ramana takes over as the head of judiciary at a difficult time. The possibility of courts reopening for physical hearing looks bleak now, given the massive spike in Covid-19 infections in the Capital.

As the CJI, Justice Ramana will have to further streamline digital hearings that have been criticised by lawyers on multiple instances due to technical faults.

Another key challenge for Justice Ramana would be to fill up the vacancies in the Supreme Court as well as the high courts, where there are just 416 judges against a sanctioned strength of 1,080.

There will also be 13 vacancies in the apex court during his tenure.

The judge would have to take measures to streamline appointments in high courts where the pendency has gone beyond five million cases. He would have to take immediate measures to convince chief justices to fast-track the process of sending recommendations, given that the HCs have not done it so far for over 200 posts.

Supreme Court advocate Sunil Fernandes sees Justice Ramana’s appointment as coming at a critical juncture.

“Every CJI has always had their fair share of challenges inside the Supreme Court. But Justice Ramana faces a massive challenge outside the court also, in the form of the resurgent second wave of the Covid-19 pandemic,” the lawyer said. “Safeguarding the image of the Supreme Court as a fiercely independent Constitutional body and timely filling up of the judicial vacancies in the SC and various HCs are the other two big challenges that I can foresee for him. But he is known for his equanimity and consensual approach and I have every reason to believe that he will do a fine job.”

Also read: SC cracks whip on HC judges appointments, sets deadline for Centre to notify collegium

Sounds good.