New Delhi: The Supreme Court Monday put on hold its November ruling, which had accepted a ‘uniform definition’ of the Aravalli hills based on an 100 metre-elevation criterion – a threshold that environmentalists said spelled a death knell for the ancient ranges.

The vacation bench of Chief Justice of India Surya Kant and justices J.K. Maheshwari and Augustine George Masih gave the latest order after taking suo-motu cognisance of the issue, which had sparked protests and uproar.

On Monday, the court ruled that recommendations of a committee of the Union Environment Ministry (MoEF)—on which the 20 November order was based—were to be put on hold, and another committee of domain experts should examine the earlier reports. The bench also issued a notice to the central government and sought the response of states where the Aravallis lie: Rajasthan, Haryana, Delhi and Gujarat.

“In the interests of justice, we direct that the recommendations submitted by the committee and directions of the Supreme Court (in the 20 November order) are to be kept in abeyance, until the case is taken up on January 21 and all states have responded,” the bench said.

The stay will remain in effect until the proceedings reach a state of finality, the court said. It further ordered authorities not to grant any new permissions for mining or renew leases without the court’s approval.

The bench drew attention to public outcry by environmentalists who expressed concern about potential damage that the definition could cause to the Aravalli ranges.

“This public dissent and criticism appear to stem from the perceived ambiguity and lack of clarity in certain terms and directives issued by this court. Consequently, there is a dire need to further probe and clarify to prevent any regulatory gaps that might undermine the ecological integrity of the Aravalli region,” the bench said Monday.

Also Read: What are the Aravallis? The decades-long quest to define a 2-billion-year-old range

‘Uniform definition’ in 20 November ruling

A bench of then Chief Justice B.R. Gavai, K. Vinod Chandran and N.V. Anjaria in November had accepted the definition by an MoEF committee.

This committee recommended that ‘Aravalli hill’ be defined as “any landform in the Aravallis”, having an elevation of 100 metres or more. The ‘Aravalli range’, it said, could be defined as a collection of two or more such hills within 500 metres of each other.

Environmentalists, and amicus curiae, had argued that these definitions would open up large parts of the Aravallis for mining, and the hills would lose their continuity.

Separately, the three-judge bench held the position that a complete ban on mining in the Aravallis would give rise to illegal operations and mafia in the region.

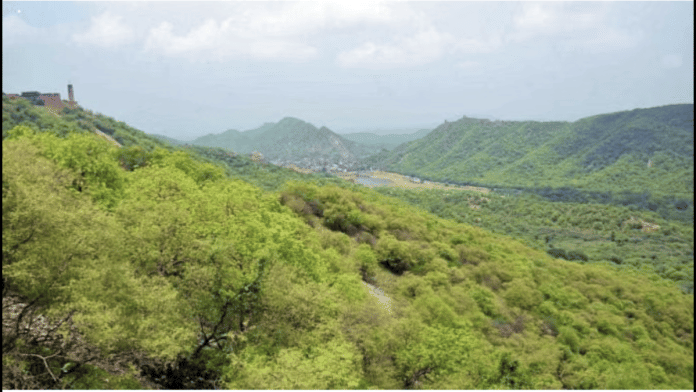

The court said that mining in the Aravallis, which act as the only green barrier stopping the Thar desert from expanding towards the fertile Indo-Gangetic plains, will be prohibited in protected areas such as wildlife sanctuaries, corridors and other sensitive zones. The lone exception would be made in cases of critical, strategic and atomic minerals, it said.

It ruled that no new mining leases should be granted until a plan for “sustainable mining” is carried out, as was done in Jharkhand’s Saranda forest area.

In the Saranda case, mining was allowed in some districts of Jharkhand while others were mapped out for conservation and protection after a study was carried out by Indian Council of Forestry Research and Education (ICFRE).

Today’s proceedings

Solicitor General Tushar Mehta, appearing for the Centre, told the court at the onset of the hearing there were misconceptions and misinformation on the issue of protecting the Aravallis.

Underlining the need for clarification, the bench led by CJI Kant suggested setting up a fresh committee to look at recommendations of all earlier committees, especially with regard to the definition of the Aravallis.

Describing the Aravallis as the “green lungs” of northwestern India, which have for centuries sustained diverse ecosystems and underpinned the livelihoods of communities, the bench said the range is an “indispensable ecological and socio-economic backbone of the region”.

Decades of unchecked urbanisation, deforestation and resource extraction have exerted immense strain upon this inherently fragile ecosystem, the court said.

S-G Mehta told the court the Centre has directed all stakeholders to ensure that no more mining licenses were given out, after which the bench said those directions must be kept in abeyance, including the ‘uniform definition’ of the Aravallis.

The court also observed Monday that the proposed definition of the Aravallis created a structural paradox, where protected territory was supposedly being narrowed down. This, it said, made it crucial to examine if the November order had inversely broadened the scope of non-Aravalli areas, facilitating mining there.

Further, the bench asked S-G Mehta if regulatory mining would be allowed in areas not considered to be the Aravallis, as per the definition, and if the answer was ‘yes’, what would be the extent of quarrying of stones permitted there.

The bench said there was a need to ensure ecological continuity of the Aravallis.

For this purpose, the new high-powered committee will study all reports by previous committees, it said. Additionally, it will need to carry out a detailed identification of areas, which would be excluded from protection under the ‘uniform definition’, and analyse if regulatory mining could result in ecological damage to the region or not.

Other specific concerns that the new committee would have to analyse is the often-cited data that only 1,048 Aravalli hills out of the total 12,081 would meet the 100-metre elevation criterion if the ‘uniform definition’ is applied.

The question of defining the Aravallis

On Monday, the bench said that the Supreme Court has been seized of the issue of mining and protection of the Aravallis since 2002.

The latest attempt at coming up with a ‘uniform definition’ of the Aravallis began after the Supreme Court started hearing two separate cases in early 2024 related to mining in the Aravallis—one in Haryana and the other in Rajasthan. Both cases examined the impact of mining in the Aravallis despite multiple court orders prohibiting it.

While hearing these cases, which were clubbed, the court observed that different states had different definitions of the Aravallis. For instance, Rajasthan follows the 100-metre elevation criterion to define the hills, but Haryana does not have any definition.

The top court subsequently ordered consultations with its Central Empowered Committee, state representatives and MoeF committee to decide on a ‘uniform definition’. The resulting recommendation, based on height of the hills, was accepted on 20 November.

(Edited by Prerna Madan)

Also Read: The guardian of the Aravallis and his 30-year fight