New Delhi: “Many decades ago, millions of citizens of India were called ‘untouchables’. They were told they were impure. They were told that they did not belong. But here we are today—where a person belonging to those very people is speaking openly, as the holder of the highest office in the judiciary of the country,” Chief Justice B.R. Gavai said at the Oxford University earlier this year.

A first-generation independent lawyer and a self-declared ‘Ambedkarite’, Gavai began his judgeship 22 years ago in November 2003 as an additional judge of the Bombay High Court.

Elevated to the Supreme Court in May 2019 and appointed India’s 52nd Chief Justice in May 2025, his six years at the top court led to a series of rulings on issues spanning federalism, criminal justice, equality, environmental governance and institutional reforms.

Shaped by home and history

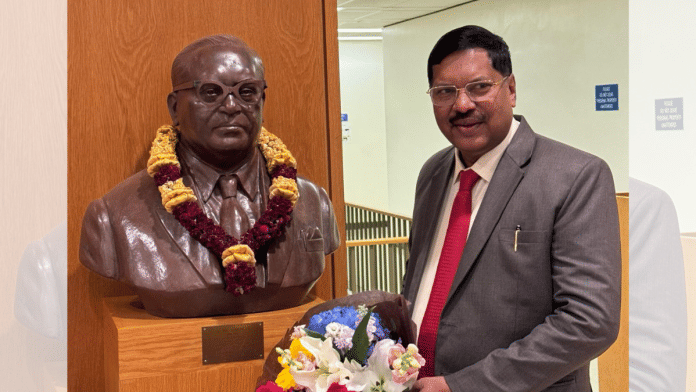

Throughout his career, Gavai acknowledged the two forces that shaped his understanding of justice—Dr B.R. Ambedkar and his father R.S. Gavai, the Dalit leader who served as the Governor of Kerala from 2008 to 2011.

He said Ambedkar’s constitutional vision and his father’s life shaped his belief that fundamental rights and directive principles were meant to co-exist, not compete.

At his farewell gathering in Delhi Friday, the outgoing CJI declared, “I demit office with full sense of satisfaction and contentment for what I have done for this country and the institution.”

The Swadesi constitutionalist

At the farewell, Senior Advocate Kapil Sibal recalled how he perceived the judiciary as an “elitist” space in the 1970s. But contemporary judges were like “Dhonis”, Sibal said, drawing a metaphor from the rise of former Indian cricket team captain M.S. Dhoni.

“For a person like you to be the CJI, the nation must be proud of it,” Sibal said, praising Justice Gavai for recognising and giving effect to diversity in the court’s functioning.

Among Justice Gavai’s final and most discussed interventions was the judgment on timelines for Governors to act on state legislations—a ruling that many said reaffirmed constitutional federalism.

After the order was delivered Thursday, Justice Gavai said: “In the Governors’ judgment, we did not use a single foreign judgment and we used Swadesi interpretation.” It captured his method – fidelity to constitutional text, and reliance on domestic precedents and Indian history over foreign scaffolding.

In the ruling, a five-judge Constitution bench ruled that governors and the President cannot be bound by judicially imposed timelines in granting assent to state legislation. This, it said, would violate the separation of powers and overstep constitutional boundaries.

Lawyers who have appeared before Justice Gavai in courts say “indigenous constitutionalism” was not posturing, but practice for him.

A wide judicial canvas

Across his six years at the Supreme Court, Justice Gavai authored or contributed to several landmark rulings, including the Article 370 case on repeal of special status for Jammu & Kashmir, striking down of the electoral bonds scheme, and permitting sub-classification among Scheduled Castes for affirmative action.

He also stayed Rahul Gandhi’s 2023 criminal defamation conviction, a decision that experts believe altered the political landscape of the time. The Congress leader’s conviction would have disqualified him from contesting the 2024 Lok Sabha election.

As CJI, Justice Gavai was instrumental in other key rulings.

He was on the Supreme Court bench that earlier this month recalled its May ‘Vanashakti’ judgment, which had barred ex post-facto environmental clearance for projects.

Earlier this month, a five-judge Constitution bench headed by Justice Gavai also declined to extend reservation to district judge appointments, noting there was no pattern of disproportionate representation in the Higher Judicial Services.

One of the less discussed but quietly transformative aspects of Gavai’s tenure was his attention to environmental issues. His jurisprudence on the subject pressed state agencies to treat forests as living ecosystems, but the orders did not obstruct development projects.

In a case on the Delhi Ridge, for instance, Justice Gavai pushed the government to revive and empower the Ridge Management Board, a body that had existed largely on paper for decades.

Though the Vanashakti order’s reversal was criticised as a setback to India’s green policies, Justice Gavai insisted that environmental permissions must follow statutory rigour and warned that “procedural shortcuts” were no substitute for ecological due diligence.

In forest rights disputes from central India, he reminded state administrations that tribal rights under the Forest Rights Act were constitutional entitlements, and directed authorities to justify any evictions.

But the Supreme Court’s nod to lift the ban on ‘green firecrackers’ during Diwali in Delhi this year was perceived as an order that did not account for the city’s air pollution crisis.

Then, there were judgments hailed as progressive.

On demolition drives carried out by governments, Justice Gavai warned states that bulldozing homes without due process “overturned the very idea of the rule of law”. His court’s partial stay on the Waqf (Amendment) Act, 2025, also signalled his readiness to check excesses while respecting Parliament’s domain.

Also Read: When final judgement isn’t final: Inside Supreme Court’s course of self-correction & the concerns

A simple courtroom

If his jurisprudence made headlines, his temperament defined his tenure. Justice Gavai was widely known for accessible rulings that were “short, but complete”, as senior lawyers put it. Many said his courts were “gentle” in manner and avoided theatrics.

Two particular incidents reflect this quality.

Earlier this year, an advocate hurled a shoe at Justice Gavai at the Supreme Court. The CJI neither flinched nor reacted angrily. Calmly, he asked the marshals to remove the advocate and resumed the hearing. He later declined to entertain a contempt case against the lawyer, not wanting to give him any more spotlight.

The lawyer later said he threw the shoe because of a statement that the CJI had made while hearing a plea about idols being hidden within sealed structures. “Go and ask the deity himself to do something,” Justice Gavai had said. This reaction was a reminder of his refusal to give weight to speculative claims and revealed clarity that cut through courtroom glamour.

A judge who listened, let others be heard

Gavai often told colleagues that “the Bar has always been my teacher”. True to that belief, he presided over courts with patience and rarely interrupted lawyers.

Even his interjections were quiet, but precise.

In August 2025, a Supreme Court division bench of Justices J.B. Pardiwala and R. Mahadevan publicly directed the Chief Justice of the Allahabad High Court to remove Justice Prashant Kumar from hearing criminal matters—after the judge treated a civil dispute as a criminal case.

The order was subsequently recalled by the same bench after CJI Gavai wrote to Justices Pardiwala and Mahadevan, and cited convention that the High Court Chief Justice was the “master of the roster”.

An equally revealing feature of his leadership were gestures that earned him goodwill.

On Karwa Chauth this year, after a formal request from female staff of the Court Registry, Justice Gavai issued a circular, granting women employees special permission to wear traditional-sober clothes to the office instead of the uniform.

Diversity push, but gaps remain

Justice Gavai, as Chief Justice, spoke of collective integrity. In June, he declared at the UK Supreme Court that he and his colleagues had “publicly pledged” not to accept post-retirement positions from the government to avoid undermining public trust.

But his tenure also showed how systemic challenges can resist quick resolutions.

While he was CJI, 129 names were recommended for High Court appointments, and 93 of them were approved. Yet, despite his advocacy for diversity, his term as Chief Justice did not see a woman judge appointed to the Supreme Court—a gap noted across the Bar and by citizens.

When he was appointed CJI in May, Justice Gavai inherited a docket of around 82,000 pending cases. By 19 November 2025, this figure was up to 90,167—an increase attributed largely to a flood of new filings and partial working of the court during the summer.

As he turns 65 and retires from the top court, Justice Gavai’s legacy rests not on sweeping reinventions, but on sturdier virtues: clarity in writing, humility in conduct, Ambedkarite conviction and Swadesi constitutional interpretation, all values that lend a steady hand during fractious times.

(Edited by Prerna Madan)

Also Read: Ayodhya to 2G: What’s a Presidential Reference under Article 143(1) & how it’s been invoked in past