New Delhi: In The Annals of Rural Bengal written in 1868, Sir William Wilson Hunter, British historian, statistician, and civil servant in colonial India, described conditions in the famine-struck Bengal countryside in the 1770s. “Tigers and wild elephants were not the most cruel enemies of the peasant,” he wrote. “Bands of cashiered soldiers, the dregs of Mussulman armies roamed about, plundering as they went.”

This situation of “lawlessness”, Hunter wrote, bred more lawlessness, and “the miserable peasantry, stripped of their hoard for the winter, were forced to become plunderers in turn”. In 1771, they formed themselves into “bands of so-called houseless devotees”, who went about begging, stealing, burning and plundering the countryside. In the aftermath of the famine, their ranks swelled as starving peasants joined them, he wrote. “The collectors called out the military; but after a temporary success our Sepoys were at length totally defeated, and Captain Thomas (their leader), with almost the whole party, cut off.”

Hunter was referring to the famous “Sannyasi Revolution” in Bengal which lasted several decades in the 18th century. His book, considered a pioneering historical and ethnographic account of Bengal at the time, along with its quintessential colonial typecasting of Muslims as oppressive invaders and plunderers, went on to become raw material for the most popular work of one of Bengal’s most prominent celebrities of the time—Bankim Chandra Chatterjee’s Anandamath or The Sacred Brotherhood published in 1882.

It was from Anandamath that the Sanskrit slogan Vande Mataram emerged in the public sphere, and went on to become, as Julius Lipner, professor of Hinduism and comparative religion at Cambridge University, says “one of the most inspiring and challenging utterances in the history of India’s birth and growth as a nation”.

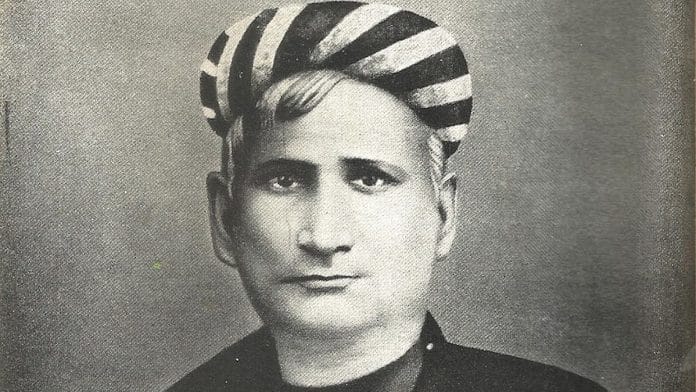

Nearly a century and a half after Vande Mataram was written, and 130 years after its author’s death in 1894, both the song and its composer are once again at the centre of political contention.

The Centre is marking 150 years of Vande Mataram, calling it not just a song but “the collective consciousness of India”.

Earlier this month, Karnataka BJP MP Vishweshwar Hegde Kageri triggered controversy by arguing that Vande Mataram, not Rabindranath Tagore’s Jana Gana Mana, should have been the national anthem. In Kolkata, Leader of the Opposition Suvendu Adhikari led a procession to College Square, where a statue of Bankim Chandra Chatterjee has been installed. Jammu and Kashmir Lieutenant Governor Manoj Sinha said Chattopadhyay strengthened the bond between “Ma Bharti” and her sons, inspiring generations in the freedom struggle.

Capping this renewed attention, reports of Bankim’s family alleging official neglect of his ancestral home and wider legacy have gone viral. Most recently, his descendants have demanded that a university in his name be founded.

As West Bengal heads for what is expected to be a fiercely fought election next year, bringing Bankim, Vande Mataram, and Anandamath back in the headlines, ThePrint explains the significance of the Bengali savant’s legacy in not just the state, but in the Indian nation at large.

The times of Bankim

The 19th century in Bengal was a period of dizzying change. By the first quarter of the century, British rule was ascendant over most of the subcontinent. English education was growing rapidly among Kolkata’s socio-economically rising Bengali middle class, the ‘bhadralok’ (gentleman). As men from this milieu took to new professions like the civil service, education, journalism, publishing, translating and the legal and medical professions, they opened themselves up to entirely new ways of seeing the world.

Ideas of “liberty”, “nation”, “patriotism”, “science” and “progress” began to animate their mental lives. Everything they and their ancestors had known and believed was suddenly rendered outmoded. Confused, this generation of the ‘bhadralok’ was desperately seeking to make some connections between the familiar and the new.

Moreover, according to Professor Lipner, as the century progressed, a “marked hauteur” replaced the initial Orientalist curiosity in the British attitude towards Indians. These newly English-educated Indians found themselves at the receiving end of what they felt was an appalling racial aversion towards them.

It was in this period marked by a deep identity crisis for the Bengali ‘bhadralok’ that Bankim was born into a respected Brahmin family in the village of Kantalpara on 26 June 1838. His father, Jadabchandra, had been appointed deputy collector in the Bengal Civil Service the year Bankim was born. Therefore, by the time he was born, the family had already been quite exposed to Western influences, which only increased in Bankim’s life as he began attending English-teaching schools.

But he was also an inheritor of an enormous wealth of traditional Sanskritic knowledge—his grandfather collected and passed on a library of Sanskrit works to Bankim. As Lipner notes in the instructive introduction to his Anandamath translation, Bankim “regularly reviewed publications with content in or derived from Sanskrit, and often referred to Sanskrit texts, expressions and passages in his writings (including Anandamath), showing a wide knowledge of the tradition”.

In that sense, Bankim embodied the quintessential educated Brahmin male of his era, who stood at the crossroads of two divergent worldviews: The modern, English-educated outlook that increasingly promised advancement in the new order, and the older Sanskritic tradition that had long defined the very terms of intellectual life.

“Bankim was a very complex product of the colonial cultural experience,” said a historian who wished anonymity. “He was the quintessential conservative Brahmin from Kantalpara, which was one of the last strongholds of Sanskritic knowledge. But at the same time, he was deeply influenced by Auguste Comte and his positivism—so he came out of that typical, peculiar colonial experience of the collision of these two worlds,” he said.

His intellectual life, was thus, an attempt to reconcile these irreconcilable worlds.

The Muslim enemy in Anandamath

In The Annals of Rural Bengal, Hunter made two significant observations that profoundly shaped Anandamath—a connection Bankim explicitly acknowledges by citing Hunter’s work in the appendices.

First, Hunter observed that it is due to the presence of a “heterogenous population of mixed descent (between Aryans and aborigines)”, that the Bengalis have never been a nation. This was, Hunter said, because “two races, the one consisting of masters, the other of slaves, are not easily welded into a single nationality”.

Second, he argued that the Aryan population of India have been subdued by conquerors over inferior intellect over and over again because the latter can wield the sword with more force. “Afghan, Tartar, and the Mogul, found the Indo-Aryans effeminated by long sloth, divided amongst themselves, and devoid of any spirit of nationality,” Hunter wrote. “Thus, for seven centuries has Providence humbled the disdainful spirit of Hinduism beneath the heel of Barbarian invaders.”

Like many Bengali intellectuals of his time, Bankim absorbed these colonial characterisations almost uncritically. Nearly a century later, in Anandamath, he gave Hunter’s Annals fictional shape—reproducing the trope of Hindus as an effeminate, fragmented people and Muslims as “barbarian invaders” who had long suppressed the Hindu spirit.

Anandamath, arguably for the first time, came up with what could decades later be described as a “Hindu nationalist” solution to the “Muslim problem”. In the novel, an army of “children”, a band of ascetic warriors, violently rise against oppressive rule in pursuit of a liberated motherland imagined as Durga. Set in the 1770s, while the novel depicts the immediate oppressive rule to be the British, but layers onto this setting a mythic-historical narrative in which Muslim rule is portrayed as a long, dark age preceding the British.

Developing a seamless overlap between the Muslim and British rulers, who were deemed equally responsible for the plight of Indian peasants, Bankim wrote in Anandamath, “The responsibility for life and property belonged to the evil Mir Jafar… He was unable to look after himself, so how could he look after Bengal? Mir Jafar took opium and slept, the British took in the money and issued receipts, and the Bengalis wept and went to ruin.”

On another occasion in the novel, one of the ascetic commanders says, “For a long time, we’ve been wanting to smash the nest of these weaver-birds, to raze the city of the Muslim foreigners (jaban), and throw it into the river—to burn the enclosure of these swine and purify mother earth again! Come let’s raze that city of foreigners to the dust! Let’s purify that pigsty by fire and throw it into the river! Let’s smash the nest of tailor birds to bits and fling it to the winds!”

It is no surprise, then, that many scholars have described Bankim as the “first Hindu nationalist,” a figure who anticipated the ideas of V.D. Savarkar and K.B. Hedgewar by at least five decades. In her book Hindu Wife, Hindu Nation, Tanika Sarkar, for instance, wrote, “Bankim was the first Hindu nationalist to create a powerful image of an apocalyptic war against Muslims and project it as a redemptive mission.”

Moreover, even as he drew an overlap between the Muslim and the British oppressor, Bankim sees value in allowing the latter to keep ruling India even as the army of ascetic warriors has destroyed Muslim rule. In the final chapter of the novel, when the character of Satyananda, a warrior, asks the ‘healer’ (arguably Chattopadhyay’s metaphoric personification of the divine) who will rule India now that Muslim rule has been destroyed, the latter says, “Now the English will rule.”

“Unless the English rule, it will not be possible for the Eternal Code to be reinstated… To worship three hundred and thirty million gods is not the Eternal Code,” the ‘healer’ says. “That’s a worldly, inferior code.” The English, he further explained, would help Hindus unlearn the “inferior code”. “And till that day comes—so long as the Hindu is not wise and virtuous and strong once more—English rule will remain intact… Therefore, wise one, refrain from fighting the English.”

‘No wedge between Bankim and Tagore’

In the late 1880s, a young Rabindranath Tagore went for a literary meeting, which was to be presided by Bankim. By this time, Bankim was already a literary giant in Bengal, while Tagore had only written a few poems, and no stories. Before the function started, the authorities garlanded Bankim. Immediately, Bankim took off the garland, and placed it on Tagore. “I am the setting sun. You are the rising sun. I must honour the rising sun. I will soon take my farewell,” he told the young poet.

Writing on whether Bankim was more influenced by his Western education or his Sanskritic heritage, Tagore wrote, “Needless to say, his mind was inspired primarily by English education… Just as the cascading stream of a distant mountaintop, when it leaves its stony bosom and flows through inhabited places makes the field surrounding its banks fruitful with crops and fruits derived from their own soil, so Bankimchandra made the new teaching fruitful by the gift he bestowed through the nature of his own language.”

“The two (Bankim and Tagore) had enormous respect for each other, so for people to draw a wedge between them is most baseless,” said the historian quoted above, referring to the ongoing political controversy in which the two are being pitted against each other. “Obviously, these people will never highlight how it was Tagore who composed the music for Vande Mataram and sang it at the annual conference of the Congress in Kolkata, after which it became the force it did.”

In fact, at a time when Muslims began to oppose Vande Mataram for its celebration of idolatry, in a letter to Nehru, Tagore wrote, “To me the spirit of tenderness and devotion expressed in its (the song’s) first portion, the emphasis it gave to the benefits and beneficent aspects of our motherland made a special appeal, so much so that I found no difficulty in disassociating from the rest of the poem, and from the portions of the book of which it is a part, with all the sentiments of which, brought up as I was in the monotheistic ideals of my father, I could have no sympathy.”

Those who are drawing a wedge between Tagore and Bankim, therefore, understand neither, the historian said.

According to Lipner, even Bankim’s views on Muslims were sometimes more nuanced than both ideological supporters and opponents of Hindu nationalism would appreciate.

In a piece written in 1873 in Bangadarsan, the journal he edited, Bankim, for instance, wrote: “Sometimes one can call a dependent kingdom free, as was Hanover and Kabul at the time of George I and the Mughals respectively. Conversely, sometimes an independent kingdom can be called unfree, as in the case of England and India at the time of the Normans and Aurangzeb respectively. We say that northern India under Kutubuddin was dependent and unfree, while India ruled by Akbar was both independent and free.”

In his novel, Rajsimha, Bankim wrote, “The author humbly submits that no reader should think that this book aims to point to disparity between Hindus and Muslims… In many cases, Muslims were better than Hindus where kingly qualities are concerned, and in many cases Hindu kings were better than Muslims in the same respect. He who has virtue (dharma) together with other qualities—Hindu or Muslim—is superior. And he who does not have virtue, and other qualities notwithstanding—whether he is Hindu or Muslim—is inferior.”

(Edited by Viny Mishra)

Also read: Tagore, Bankim & the battle for Bengal’s soul—BJP caught in its own cultural crossfire