New Delhi: The raging debate these days is about “Nepotism vs Talent” in Bollywood, or as a section puts it, the “Insider vs Outsider”, sparked by the death of actor Sushant Singh Rajput.

Like most raging debates, a lot of the discussion around it has been inaccurate and agenda-driven. The topic of “Nepotism vs Talent” itself is at best a lazy effort by a headline hunter. At worst, it’s a deliberate eyewash to appeal to the lowest common denominator in TV debates.

Bollywood’s monopolists vs disruptors

Bollywood loves to refer to itself as a business or industry. There was a time when we determined a movie’s success by how long it ran continuously in theatres. There would be a party if a movie achieved a Silver Jubilee (25 days) or a Golden Jubilee (50 days).

But these days, we have a much simpler benchmark. To decide whether a film is a hit or a flop, we rely on Bollywood trade analysts (again a recent phenomenon) to tell us how much money a movie has made. Instead of the jubilees, we have the Rs 200-crore and Rs 300-crore clubs.

Now don’t get me wrong. This is not a rant on the good old times. If Bollywood is indeed a business, there is nothing wrong in using the parameter we use to judge the success of any business — revenue.

We should, in fact, go one step further and start introducing some business jargon into our Bollywood debates. So next time someone tells you about this “Insider vs Outsider” battle, tell them it’s actually a battle of “Monopolists vs Disruptors”.

Monopolist is a term that has a negative connotation in our usual discourse, although essentially, creating a monopoly is the fundamental goal of any business. As a business, you always want to reach that utopia where no competitor can ever touch you. As an example, Google right now is monopolising the market of internet search.

In a free market, a private enterprise like a movie studio can hire at its discretion anyone it sees fit for a role. Whether the actor, writer, musician, or any other craftsman involved in movie making has any family connections with the studio is immaterial. The studio also has the right to pursue its profit motives with all fair means possible.

Things, however, start to go wrong when a monopoly starts to use means that makes the market anti-competitive. When that happens, a disruptor doesn’t have a fair chance of competing in the same market and indeed at some point, becoming the next “disruptee” by displacing the current monopoly.

So while there is nothing wrong in casting your own son as the lead for a movie you are making, blocking 80 per cent of theatres across the country during the festive season may qualify as anti-competitive.

In legal terms, we call this antitrust. One of the more famous antitrust cases was filed against Microsoft for practices that restricted other software makers from having a fair shot at creating a browser for Windows OS.

If you read through it, the Microsoft business case looks quite similar to big Bollywood studios restricting smaller filmmakers from getting a theatrical release.

A business that is fair and competitive requires a regulator. The regulators of the stock market, for example, try to make sure there is a fair and level playing ground for all investors, big or small.

But as Shekhar Gupta noted in his recent piece, expecting a Bollywood regulator is a tough ask in an industry with “no elder statesman, no institution like an association or an Academy, few journalists who carry credibility as well as weight, no whistle-blowers”.

If Bollywood is a “dirty picture”, then the act of cleaning it up would involve creating some sort of regulator, internal or external, to ensure a level playing ground for every artiste to create art that is profitable.

Otherwise, even if current outsiders get their break someday, they will eventually become like the current insiders and repeat the same malpractices.

Also read: Dil Bechara review: Sushant Singh Rajput’s last outing is touching, but needed better writing

Is cricket better than Bollywood in providing opportunities?

The only entertainment business that compares with Bollywood in terms of its revenue and reach is cricket. It’s worth comparing the two and see if there are lessons to be learnt.

The Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI) has an unchallenged monopoly over the business of cricket. The only worthy competition it ever got since its inception was from the Indian Cricket League(ICL).

It dealt with ICL by banning any players who took part in India’s first major domestic T20 league. In the past, the BCCI has tried to monopolise the global game itself by creating a coterie with England and Australia — the “Big 3” power centre.

The BCCI clearly isn’t a role model when it comes to encouraging fair competition with a business rival. But when it comes to giving a fair chance to everyone who picks up a bat and a ball, Indian cricket system has done reasonably well over the years.

In Nasser Hussain’s beautifully shot documentary on Mumbai cricket, the former England captain explores how the city’s system identifies talent at an early age and rewards it, irrespective of a player’s background and last name.

A kid scoring consistent big runs at Shivaji maidan catches the fancy of Mumbai cricket elites in no time, who then play their part by nurturing and fast-tracking the talent for success at the highest level.

The story of a middle-class Mumbai kid named Sachin Tendulkar isn’t just a victory of his talent, but also a triumph of the system. First, a dedicated Ramakanth Achrekar gives him special treatment in his budding days. When, as a 14-year-old, he misses out on getting recognised as the best junior cricketer at the school level, he receives a personal letter from Sunil Gavaskar, no less.

When he needs financial help to get exposure overseas, Raj Singh Dungarpur comes forward and helps him with sponsors.

And while Indian cricket till the 1990s could have been considered a hegemony of a few major centres, the last two decades have seen the rise of hungry small-town kids making it to the highest level. But if you take the career graph of any of these kids, you will still find existing stalwarts had a role in their rise.

Take M.S. Dhoni, for example. When a swashbuckling, self-taught wicket-keeper from Ranchi with an unorthodox technique caught the attention of the then Indian captain, Sourav Ganguly, he asked the selectors to pick him for India’s tour to Bangladesh in 2004.

A few months later, Ganguly gives up his own batting spot and promotes Dhoni to bat at number 3 in a star-studded batting line-up. Dhoni grabs the opportunity with both hands to score a match-winning and career-defining 148 against Pakistan.

Later on, when there is a leadership crisis in the team, Sachin Tendulkar steps forward and recommends Dhoni’s name to captain the Indian side at the inaugural 2007 T20 World Cup. The rest, as they say, is history.

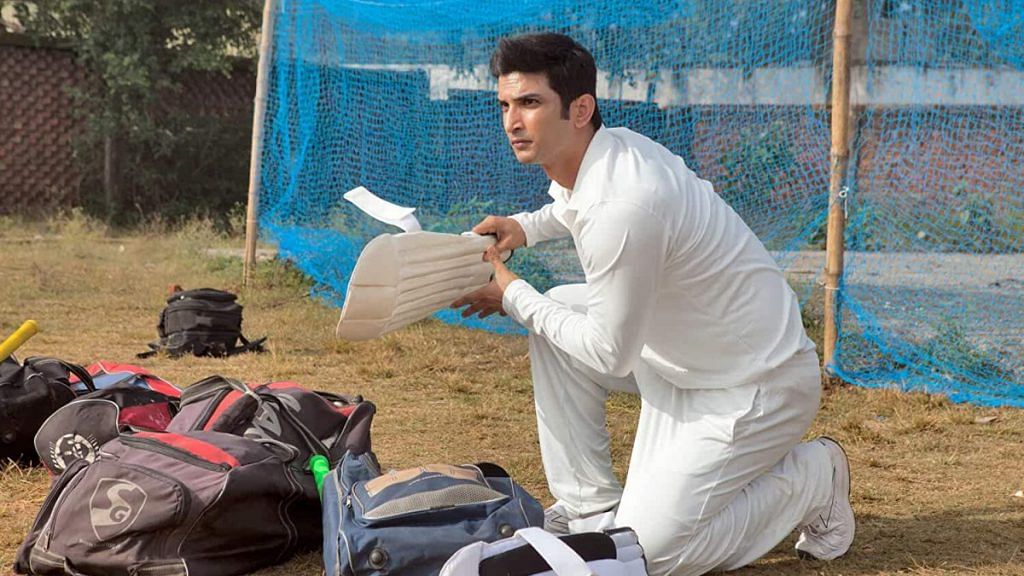

It is this system of patrons and senior statesmen that Bollywood lacks. The irony of a Sushant Singh Rajput, who was born in the same state as Dhoni (Ranchi was once part of Bihar) and who played the former Indian captain in his biopic, not finding the same kind of support from a cut-throat industry shouldn’t be lost on us.

Unlike cricket, Bollywood doesn’t seem invested enough in getting better by unearthing the next generation of talent. One thing that works in cricket’s favour is the fact that it’s easy to recognise talent based on the sheer number of runs and wickets, but there is no objective benchmark to judge the calibre of an actor or a writer.

But while identifying the best among a group of talented actors is a subjective exercise, it’s easy to spot an objectively bad actor. If Bollywood can start with telling these non-performers (many of whom are star kids) that you don’t belong, it will be a significant first step towards making it a less nasty and a more inclusive place.

Rajesh Tiwary tweets @cricBC and is known for his blend of cricket insights and irreverent humour. A self-confessed cricket geek, he prides himself in remembering every frame of grainy Television cricket coverage of the ’90s.

Also read: Nepotistic privilege should be a matter of social shame. It holds India back