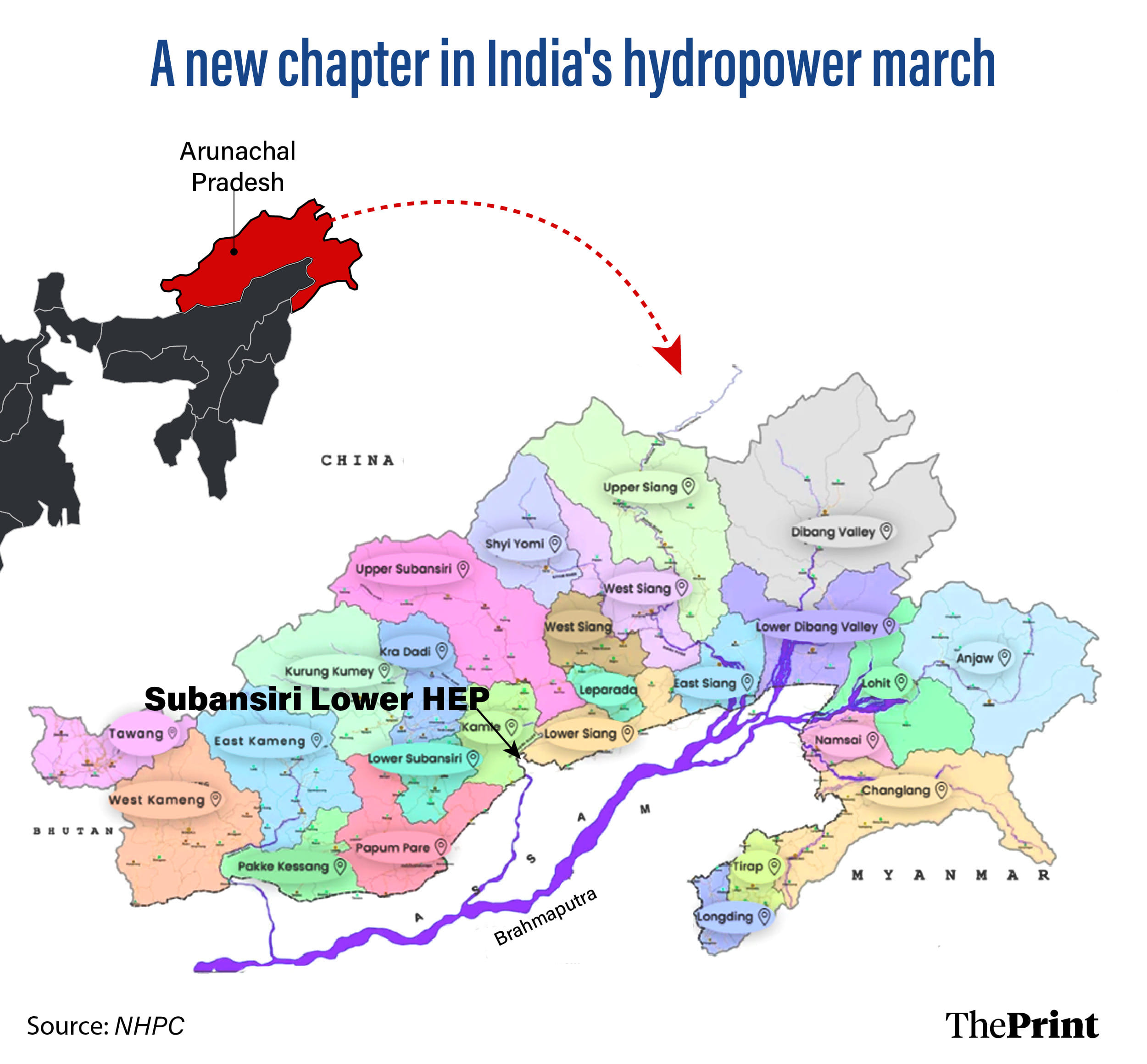

Kamle (Arunachal Pradesh)/Dhemaji (Assam): Gerukamukh, a non-descript village on the Assam-Arunachal Pradesh border is a small dot on India’s map, but make no mistake of its importance given the presence of the Subansiri, the largest tributary of the Brahmaputra, in shoring up the North-East’s energy security.

Located near Arunachal Padesh’s Kamle district, a little over two-hour drive from Dibrugarh, the quaint little village is where India’s largest under-construction hydro power station—the 2,000 MW Subansiri Lower Hydro Electric Project (SLHEP)—is in the process of getting commissioned.

While 50 percent of the SLHEP structures, located upstream, including the main dam and the water conductor system that carries water to run the turbines, falls on the river’s right bank in Arunachal Pradesh, the other 50 percent downstream including the 2,000 MW power station is on the left bank in Assam’s Gerukamukh.

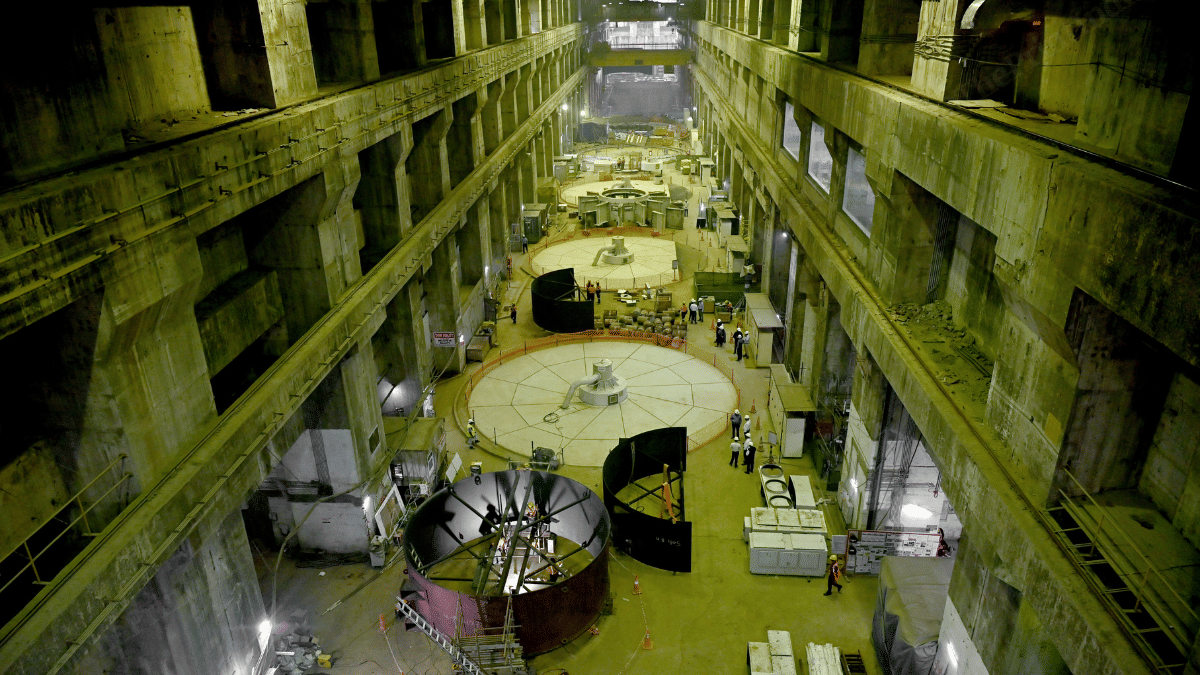

Four of the power station’s eight units, each with a capacity of 250 MW, will start commercial operations between mid-November and December-end. The trial run of one of the units was initiated less than a fortnight ago. This will be followed by three more units.

The remaining four units of the same capacity are nearing completion and will be commissioned next year.

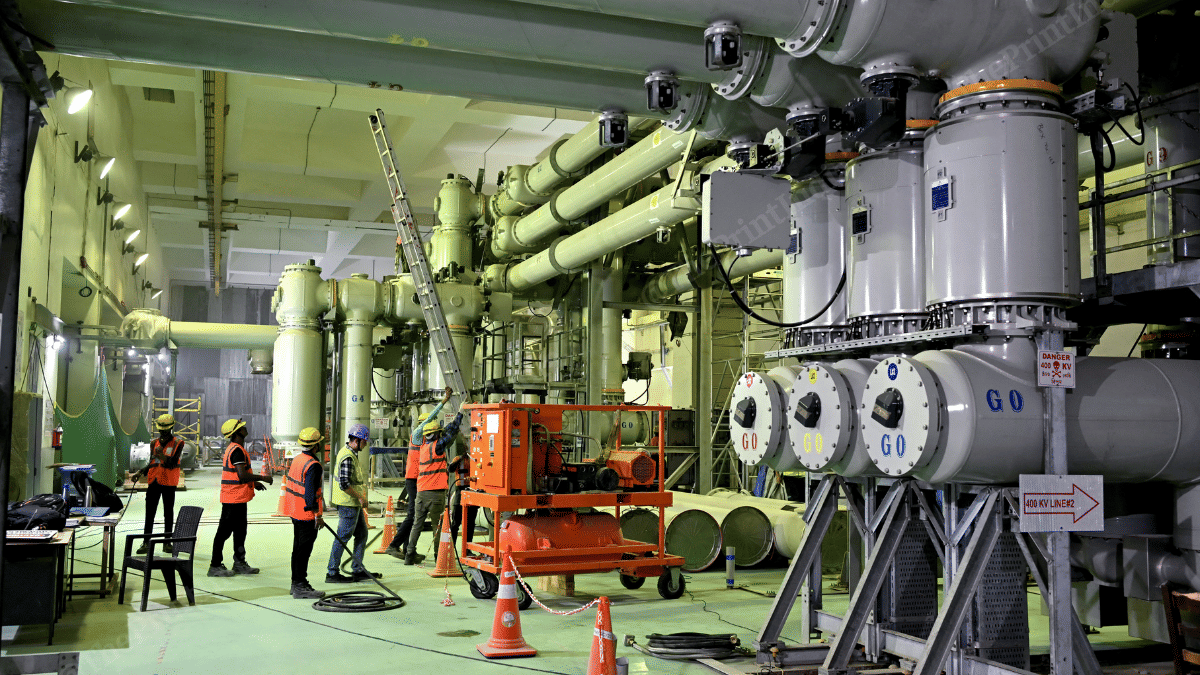

Last weekend, when ThePrint visited the dam site, work was going on at a frenetic pace despite the incessant rain. Workers donning yellow, blue and white helmets were busy testing the machines and equipment before the commissioning.

A control room has been set up near the dam site, which is manned by officials of National Hydroelectric Power Corporation (NHPC) round-the-clock. Inside, a small machine with dozens of lights in red, green and yellow colour monitors the flow of water in the Subansiri.

NHPC executive director and SLHEP project head Rajendra Prasad told ThePrint that an early flood warning system has been installed in Daporijio, 71 km upstream and Tamen, 53 km upstream of Subansiri, which would immediately indicate if there was a sudden high discharge of water in the river.

“We will know five-six hours in advance if a flood is coming and there is intense rainfall. Once we get the warning, we will initiate the necessary protocol to regulate the excess discharge to prevent flooding the downstream villages in Assam,” Prasad said.

At its peak—before work was stalled in 2011—close to 8,000 workers, a majority of whom from Assam, were working at the site. “Now, with the project almost complete, the number of workers has come down to half,” a senior NHPC official at the dam site said.

Prasad said that at present 96 percent work is completed. “The dam structure, nine spillway gates (to release the surplus water downstream), water conductor system and four of the units in the power station are ready. The wet commissioning of the first unit has started,” he added.

The trial run is being seen as a kind of milestone for the project. And, rightly so.

Also Read: While China builds its mega dam on Brahmaputra, India’s long-delayed Subansiri marks key milestone

Costly delay

The SLHEP has been in the making for the last 20 years. While the Union cabinet had approved it way back in 2003, India’s largest hydropower developer NHPC started construction on this mega project on the Subansiri in 2005.

At that time, the estimated cost of the project was Rs 6,285 crore and its completion deadline was 2012. But the humongous delay led to an over 50 percent escalation with the cost shooting to Rs 27,000 crore at present day prices.

Mounting protests by local communities and anti-dam agitators, some of whom also petitioned the National Green Tribunal (NGT) against the construction over environmental and social concerns, led to suspension of work in 2011.

It was only in 2019 that the NGT gave the go ahead for work to resume. On account of the delay, the per day loss to NHPC because of work getting stalled, was to the tune of Rs 5 crore, senior NHPC officials said.

Prasad said that in the last one year, interest during construction has come to approximately Rs 1,000 crore. “And the overall completion cost is Rs 27,000 crore as per today’s price level. The cost has increased by over 50 percent today. If work was not stalled in 2011, the project would have been completed near the sanctioned cost.”

For context, the Brahmaputra Board first envisaged construction of a 257-metre high rockfill dam at Gerukamukh on the Subansiri in 1983. But this original proposal could not be pursued because of objections from Arunachal Pradesh due to the possibility of submergence of some important towns like Daporijo, Dumporijo, Tamen and a few small villages.

The proposal was reworked and handed over to the NHPC in 2000. The delay had other fallouts, too. Big contractors like L&T, who were working before the project got stalled, left.

In fact, protests against the dam are still continuing. A group of protesters are currently sitting in Assam’s Dhemaji district, almost half-an-hour away from the dam site. The bone of contention is the inequitable share of free power given to the state from SLHEP.

From the 2,000 MW installed capacity of the project, Arunachal Pradesh has been allocated 274 MW. Of this 240 MW will be free as per the Centre’s policy mandating 12 percent free power to the home state (because of submergence and displacement of population caused by the project).

Though Assam has been allocated more (533 MW), its share of free power is just 25 MW. “This has been given partly due to the likely downstream impact of the dam and agitation by locals. Arunachal being the host state, where most of the dam infrastructure is located, has got the bulk of the free power share,” an NHPC official said.

While five other north-eastern states of Manipur, Meghalaya, Nagaland, Tripura and Mizoram have been allocated 198 MW, the remaining power will be shared by five northern states/Union Territories of Haryana, Punjab, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh and Chandigarh and five western states of Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, Chattisgarh, Maharashtra and Goa.

Unlocking potential

The SLHEP is the first of the cascaded dams on the Subansiri being developed primarily for hydro power.

A mega project with three components—the 2,000 MW Subansiri Lower, the 1,600 MW Subansiri Middle, also called the Kamle, and the 2,000 MW Subansiri Upper projects—has been envisaged on the Subansiri basin. While the SLHEP will be commissioned next year, prelimnary investigations has already started on the Kamle and Upper Subansiri projects.

Besides these, the NHPC has also started the construction of a 2,880 MW multipurpose project on Dibang river in the lower Dibang Valley.

In all, close to a dozen large and small hydro projects have been proposed in Arunachal Pradesh. This includes the largest so far—the 11,200 MW Upper Siang multipurpose project—conceived as a counter to China’s mega dam push on the Brahmaputra in Tibet, where it is known as Yarlung Tsangpo.

These ongoing, under construction and proposed projects will give a big leg up to the North-East and India’s energy security.

“Subansiri will serve as the gateway for future hydro projects in Arunachal Pradesh, unlocking the immense hydro potential of the region. Its successful completion will reflect India’s commitment to clean energy, ecological balance and inclusive development—a vital step towards the country’s energy transition and the Net Zero 2070 goal,” NHPC chairman and managing director Bhupender Gupta told ThePrint.

SLHEP will not just bolster the energy security of the region. It will also have a flood cushion to lessen its impact. Floods in Brahmaputra wreak havoc in the region during monsoons.

Prasad said that despite apprehension that SLHEP will cause flooding in downstream villages in Assam, it was not to be during 2024 and this year’s monsoon.

“Last year, on 30 June and 1 July, there was a flood of 1,200 cumec. But we could regulate it by first lowering the reservoir level and accommodating the excess discharge coming from upstream. Once the peak flood was over, we released the water in a staggered way preventing flooding of downstream areas,” he said.

Similarly, this year also on 31 May and 1 June, there was excess discharge from upstream of Subansiri, to the tune of 10,000 cumec. “We again regulated the discharge.”

As the project developer, the NHPC has also undertaken river protection work downstream as per the recommendation of the joint committee comprising central and state officials.

“While flood control and river protection is the state government’s job but because of pressure from people living in downstream areas, we undertook the work,” the official quoted earlier said.

The developer spent Rs 522 crore on river protection work and livelihood programmes for women in downstream villages that are vulnerable.

Also Read: Chinese checkers: India readies masterplan to draw 65 GW hydropower from Brahmaputra basin

No easy task

There were several other challenges, too. NHPC officials said there were geological surprises throughout the construction period. “There were challenges due to flash floods. We used to work during lean season after controlling and diverting the river water,” an NHPC official said.

Diversion tunnels, which are temporary structures to facilitate construction, were built for this purpose. But the bigger problem started once work resumed after eight years in 2019.

“Some of the structures became defunct. For example the structures built to divert water from the main dam site were designed for 72 months (construction period). But over the eight year period, the diversion tunnels were damaged….water was flowing along with huge logs and trees, which resulted in erosion. This affected the tunnel as they were not designed for this,” a second NHPC official said.

Soon after work resumed, a natural disaster struck. In June 2020, a landslide near the project site cut off the access road to the dam. Landslides again disrupted work in 2021, 2022, and 2023. Work finally picked up pace in 2024.

However, unlike other big ticket infra projects, SLHEP is probably one of the few that has caused zero displacement. There were other issues though.

On Subansiri’s upstream, agricultural land in two villages—Gengi and Siberite—were affected. A total of 77 project-affected families were identified for compensation.

There were many other claimants, too. “Villagers demanded compensation for the forest land as they claimed they had rights over it. This is only there in Arunachal Pradesh. We paid compensation to the tune of Rs 300 crore as per the Net Present Value (NPV) of the forest land,” the second NHPC official said.

The overall compensation paid to the locals was Rs 650 crore of which around 50 percent comprised NPV of forest land. The compensation process is over now and most of the contentious issues have been resolved.

According to CMD Gupta, the positive support and proactive role of the central, state governments and its agencies was instrumental in resolving long-pending challenges and ensuring the steady progress of the landmark SLHEP project.

(Edited by Tony Rai)

Also Read: Through forests & mountains, how Rlys overcame hurdles to build Mizoram’s Bairabi-Sairang line