New Delhi: Last week, senior Vishva Hindu Parishad (VHP) leader Champat Rai appeared to contradict the Sangh Parivar’s decades-long assertion of a pan-Hindu identity by saying that the Ram temple belongs to the Ramanandi sect, and not to the Sanyasis, Shaktas or Shaivites.

Responding to a question on what prayer method would be followed during the temple’s consecration in an interview with Amar Ujala (a Hindi daily), Rai, who is the general secretary of Shri Ram Janmabhoomi Teerth Kshetra and vice-president of the VHP, said that it would follow the Ramanandi parampara since the temple belongs to the Ramanandi sect.

The Shankaracharya of the northern peeth, Avimukteshwaranand Saraswati, retorted by asking for Rai’s removal from the temple trust since he himself is not a Ramanandi.

Deccan Herald also quoted a mahant of the Nirmohi akhara — an order that is part of the Ramanandi sect — as saying that the trust was not following the Ramanandi parampara in the proposed consecration. “We want the rituals and worship of Ram Lalla to continue in accordance with the Ramanandi traditions, but the trust has ignored our plea,” he reportedly said.

Meanwhile, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) and VHP have sought to downplay Rai’s statement and the sudden focus it has brought on the Ramanandi sect.

“Hinduism has many sects — Vaishnavism, Shaivism, Jainism, Shaktism, etc., Ramanand is one of them, but they are all part of Hinduism,” Manmohan Vaidya, joint general secretary of the RSS told ThePrint.

“So, there is no contradiction — his (Rai’s) statement was limited to the question of who will perform the puja, and not about who can come and take darshan…everyone will come and take darshan,” Vaidya added.

VHP working president Alok Kumar, on the other hand, refused to comment on Rai’s statement.

A historian, who requested anonymity, said that Rai’s assertion is “curious” and would be “absolutely unacceptable” to most Hindus who are awaiting the consecration ceremony of the Ram temple.

“It flies in the face of their (the Sangh Parivar’s) own attempts to forge a common Hindu identity over several decades,” the historian said. “Moreover, how the temple is ‘owned’ by the Ramanandis needs investigation — I don’t think such a claim has been made before.”

The Ramanandis are said to have maintained the ‘Ram temple’ for several decades, even when the Babri Masjid stood at the spot until 1992. Beyond this, very little is known about the sect, or even its founder, Swami Ramananda.

Richard Burghart, a German anthropologist who is one of the few scholars to have worked on the Ramanandis, published a paper titled ‘The Founding of the Ramanandi Sect’ in 1978. In it, he writes, “The one thing which we do know is that we know very little indeed about Swami Ramananda; moreover, for a very long time our ignorance has been shared by the Ramanandi ascetics themselves.”

So, who was Swami Ramananda? Who are the Ramanandis? Were they orthodox Hindus or reformers? What has their relationship with other Hindu sects been like? Were Muslim rulers their enemies or patrons? ThePrint explains.

Also Read: Congress just blew a Ram-given opportunity. It chose chronic confusion over national mood

Who are the Ramanandis?

According to most accounts, the Ramanandi sect was founded in the 14th century by Swami Ramananda. But as argued by Burghart, the most basic facts about Ramananda — like when and where he was born, or when he died — are not known with any degree of certainty.

Indeed, William Pinch, a historian of South Asia, argues that it remains in the realm of possibility that Swami Ramananda was “conjured up” by monks of the Ramanandi order retrospectively to organise and give “Brahminical respectability” to their order.

What we do know for sure, however, is that the Ramanandis belong to the larger Vaishnav sect within Hinduism and that they are worshippers of Ram — an avatar of Vishnu — Sita and Hanuman. While Vaishnavites are worshippers of Vishnu, Ramanandis only worship his Ram avatar and not Krishna, for example. As a whole, the sect is distinct from Shaivism, the sect that worships Shiv, or Shaktism, the sect that worships the goddess Shakti. Durga, Kali, Parvati, are all personifications of Shakti.

Vaishnav bards say that many revered figures such as Tulsidas, Mira Bai, Kabir, Ravidas, and Padmavati are all spiritual descendants of Swami Ramananda.

The sect’s monasteries are found across Bengal, Bihar, Odisha, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Gujarat, Rajasthan, Punjab, Haryana, and Uttar Pradesh, as well as in the Nepal Valley and the Nepalese Tarai — a testament of their geographical spread and influence. Indeed, the Ramanandis are said to have the longest procession in the Kumbh Mela till date, writes Pinch.

Yet, their history remains shrouded in ambiguity.

In stark contrast to the tentativeness of contemporary scholars, however, the Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics, written between 1908 and 1921, offers some definite “facts” about Ramananda and the Ramanandis.

According to the Encyclopedia, edited by Scottish clergyman James Hastings, Ramananda was born in Prayag (present-day Prayagraj) in 1299 AD as Ramadatta, and by the age of 12, he had become a “finished pandita”, who then left for Benares (Varanasi) to study philosophy.

It was here that a young Ramadatta was initiated into the Sri Vaishnava sect founded by Ramanuja in southern India by Raghavananda — one of the sect’s most prominent teachers — who gave him an initiatory mantra.

Even now, Ramanandi ascetics are initiated by receiving a secret mantra from their respective gurus, which, it is believed, eventually links all Ramanandi ascetics back to Ramananda, or even to the Hindu deity Ram himself — some Ramanandis believe that Ramananda was an incarnation of Ram.

However, the Vaishnava sect into which Ramananda was initiated is believed to have consisted only of Brahmans, who observed strict dietary restrictions and wrote and learned only in Sanskrit.

Ramananda was to change that by forming his own sampradaya or sect. “This,” the Encyclopedia noted, “resulted in one of the most momentous revolutions that have occurred in the religious history of northern India.”

The Bhakti tradition and its myriad religious reforms, which started in the south of India, are said to have come to the north through this new sect — Bhakti Dravid upji laye Ramanand (Ramananda brought the Bhakti from the south up north) goes one popular saying.

Women, Muslims, “lower” and “untouchable” castes — all were recruited into this new, revolutionary sect.

One of the most popular sayings attributed to Ramananda is “Let no one ask man’s caste or with whom he eats. If a man shows love to Hari (another name for Ram), he is Hari’s own.”

Sanskrit ceased to be the only language of spiritual and religious learning. All teachings started to be mostly done in the vernacular. Most scholars agree that it is owing to the voluminous works of Ramananda’s followers like Kabir, if not Ramananda himself, that Hindi became a literary language across the north.

Perhaps the most significant consequence of this phenomenon for centuries to come was the writing of the Ramcharitmanas by Tulsidas in the vernacular Awadhi language in the 16th Century.

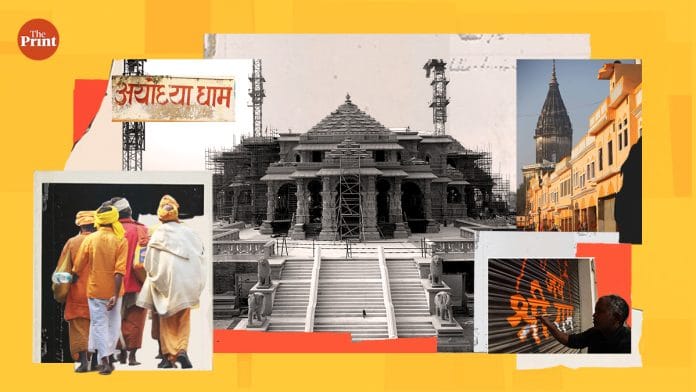

As the Ramanandis continued to establish their presence, the significance of the Ram temple in Ayodhya became a focal point for their identity and beliefs, intertwining with the broader narrative of Hindu resurgence.

The Hindu-versus-Hindu battle over ‘Ram Janmabhoomi’

Until the 18th Century, however, the Ramanandis were predominantly operating in western India, especially in Rajasthan and Punjab.

How they amassed and consolidated power in Ayodhya, which they believed to be the birthplace of their supreme deity, is a story of deadly battles and power contestations — among Hindus.

As argued by Pinch in his book, Peasants and Monks in British India, the establishment of the Ramanandi akharas — militarised orders of the sect — in Ayodhya was hardly smooth.

In the early 18th century, the Dasnami sect of the Sanyasis captured Ayodhya on Ram’s very birthday, thereby driving away the Ramanandis. Startled by this aggression, Vaishnavite sects called for a historic conference in Galata near Jaipur, after which the Ramanandis began to organise themselves militarily into akharas.

One of the first armed sects of the Ramanandis that came to Ayodhya to unseat the Sanyasis in the early 18th Century was the Nirmohi akhara. This akhara went on to become one of the main plaintiffs in the Babri Masjid-Ram Janmabhoomi title suit over two centuries later.

They were followed to Ayodhya by other Ramanandi akharas, including the Nirvani and Digambari. By the close of the century, the militant orders of the Ramanandis and Sanyasis were locked in deadly, armed combat. Ultimately, however, the Dasnamis were pushed out of Ayodhya.

VHP leader Rai’s statement that the Ram Mandir belongs to the Ramanandis and not to the Sannyasis is linked to this 300-year-old enmity.

The Shaivites and Muslims were the lesser enemies, at least in Ayodhya. According to a local legend recounted by Krishna Jha and Dhirendra K. Jha in the book Ayodhya: The Dark Night, there once was a Hanuman idol placed under a tree at Hanuman Tila in Ayodhya — the site that eventually became Hanumangarhi.

The idol was worshipped both by Shaiva nagas and Muslim faqirs. However, upon their arrival in Ayodhya, the nagas of the Nirvani akhara of the Ramanandi sect drove both the Shaivites and Muslims away from the idol of “their” deity, Hanuman.

But there was yet another twist.

The ones to help the Ramanandis in turning Hanuman Tila into a temple and then a fortress, Hanumangarhi, were the nawabs of Awadh.

From the time of Nawab Safdarjung to his grandson, Asaf-ud-Daullah, lands and funds were generously granted to the Nirvani akhara, and Hanumangarhi thus became their main seat of power with the help of Muslim rulers.

Also Read: Why Ayodhya’s Suryavanshi Thakurs will end 500-yr-old vow, don pagdis with Ram Lalla’s consecration

Printing press and emergence of ‘Muslim enemy’

In the 19th century, the forms of communication and transmission of religion and religious teachings were fundamentally altered across religions and sects. The reason was the coming of the printing press to the Gangetic north.

The Ramanandis were not immune to this. The core Ramanandi hagiographical text, Bhaktamal, written in 1660, started being reproduced in accessible forms for everyone to read and consume in short, printed copies in Hindi. Until then, one of the most widely read commentaries on the text had been a work in Persian.

Edition after edition of the Bhaktamal was published. The history of the sect, which had hitherto existed in a state of comfortable ambiguity even among its staunchest followers, began to be contested with a new zeal to “settle” it, wrote Pinch.

Those within the sect who could narrate the most convincing past would have the greatest power and influence over it.

In this milieu emerged the radical Ramanandis. They sought to cut off any link that Ramananda may have had with Ramanuja from the south.

Ramananda had single-handedly founded the order of which they were a part, these new radical Ramanandis claimed.

Ramanujas’ Sri Vaishnavite followers, they felt, were casteist and elitist, and did not represent their sampradaya in any way. An intra-sect conflict thus ensued.

From 1918 to 1921, fierce debates between the Ramanandis and followers of Ramanuja took place in Ayodhya and Ujjain, with the increasing erasure of Ramanuja’s connection with the Ramanandi sampradaya. The new, radical and aggressive Ramanandis increasingly emerged as the dominant voice of the sect.

As other questions were “settled”, a relatively new concern began to creep into the works of the radical Ramanandis — the coming of Islam to India, a major colonial intellectual and historical preoccupation of the time.

This new history began to portray Ramananda as a champion of Hinduism in the face of Muslim persecution.

Increasingly, the Vaishnava-Shaiva conflict began to be decried as a “Hindu-versus-Hindu” rivalry, which ultimately weakened Hinduism and led to its decline vis à vis

Islam, argues Pinch.

“The new Ramanandi historiography relied on a depiction of Muslims as unidimensional villains bent on the destruction of a divided Hindu society,” writes Pinch. The patronage received by the Ramanandis from the nawabs in Ayodhya just two centuries ago had no place in this new history.

Colonial historiographies played a significant role in enabling this history.

The Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics quoted above, for instance, argues that if Ramananda lived from 1299 to 1410 — giving him an unusually long life of over 110 years — he would have witnessed the “tyranny” of different Muslim rulers from Alauddin Khilji to Muhammad bin Tughlaq.

“It is impossible not to believe that this series of calamities exercised much influence on Ramananda, and that his doctrine of faith in the benignant and heroic Ramachandra (Ram)…owed much of its acceptance to the sufferings then being undergone by the Indian people under cruel, alien rule,” it said.

It was in this context of the early and mid-20th century that Abhiram Das — a muscular ascetic priest of the Ramanandi sect in Ayodhya — was accused of having placed Ram’s idols inside what was then the Babri Masjid two years after the Indian independence on the night of 23 December, 1949.

Since then or perhaps even earlier, the “temple” has been maintained by the Ramanandis — not Sanyasis, Shaivites or Shaktas, as Rai has emphasised— before it was handed over to the Shri Ram Janmabhoomi Teerth Kshetra Trust in 2020.

(Edited by Richa Mishra)

Also Read: Who should get credit for Ayodhya Ram Mandir: Advani or Modi? Answer blows in the wind