New Delhi: While waiting in line at an Indian Oil petrol pump in Delhi’s Indraprastha, 52-year-old Vijay decided at the last minute not to renew his pollution certificate there. He knew that his 5-year-old mini truck might run into complications at the Indraprastha PUC (Pollution Under Control) Centre, and that’s a risk he would rather not take.

“Here they’re quite strict with the tests,” he told ThePrint. “There are places where they don’t even check it, so I know I’ll get a certificate regardless of my car. Why bother here then?”

Vijay isn’t wrong. A Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) report on vehicular pollution in Delhi, tabled in the Delhi assembly Tuesday, said there were more than 5 lakh diesel vehicles in the capital that got pollution control certificates despite not passing the emissions tests, in the five years between 2015 and 2020. In fact, the CAG report laid bare the malpractices of the entire pollution control certification system in Delhi.

Vehicular emissions have been routinely flagged to be the highest source of air pollution in Delhi, across winter and summer. According to a 2024 study by IIT Kanpur, local vehicles and traffic emissions are the largest contributors to Delhi’s air pollution.

A 2018 study by TERI, an independent institute, said that the transport sector causes 40 percent of the total emissions in the city. Yet, there is only one main mechanism to monitor the emissions caused by individual vehicles—the pollution under control certificates (PUCs) mandated by the central government.

“I’ve gotten valid pollution certificates sometimes without even taking my car to the centre—just a picture of my license plate suffices,” said a South Delhi resident, asking not to be named. “It’s easier in Noida and Ghaziabad, but some places in Delhi do it too.”

The Pollution Under Control (PUC) certification system was introduced in 1989 under the Motor Vehicles Act, 1988, and was mainly aimed at identifying polluting vehicles. They then need to either be repaired or removed from the road. It is mandatory for any vehicle active in India to have a PUC certificate. These certificates—the validity for which lasts either three months or 1 year, depending on the kind of vehicle—are generally issued by PUC centres located near or at petrol pumps or service centers, and it is in these centres where the problem lies.

“Just like any other government policy, here too there is scope for corruption,” explained Tutu Dhawan, automotive expert. “I’ve heard that for any amount between Rs 50 and Rs 500, you can get a valid PUC certificate without the necessary checks.”

This problem was flagged by the CAG report. The report, which analysed the factors behind Delhi’s air pollution, also highlighted the other major issues with the PUC certification system—malpractice in issuing certificates, lack of proper equipment, and poor monitoring of PUC centres. The report was submitted in 2022 but was only tabled in the Assembly this week.

“This was a problem that went right up to the top—the PUC centres’ corruption had been flagged, but the higher officials didn’t take any action,” Delhi Environment Minister Manjinder Singh Sirsa said told ThePrint. “If they (the former government) wanted to fix the issue, they wouldn’t have hidden this CAG report for two years.”

The Aam Aadmi Party, on the other hand, stood its ground, saying that Delhi’s PUC centres are more stringent in their testing than other states. Gopal Rai, former Minister of Environment of Delhi, told ThePrint that the CAG report also mentioned the positive initiatives taken by the government against pollution.

“If you compare to PUC checking in nearby states of Delhi, you’ll find out how strict our centers actually are,” said Rai. “And the CAG report does not mention corruption anywhere. Instead, it talks about how AAP managed to increase the number of good air days in a year from 109 to 209.”

Also Read: Delhi’s air was toxic for 56% of the days in last 5 years, AQI no reliable measure—CAG report

Problem with certificate issuance

The process of getting a PUC certificate is a simple one—once the vehicle is taken to a centre, the operator inserts a small probe into the exhaust tailpipe of the vehicle. This probe is connected to a machine called the emissions analyser, and when the engine is turned on this analyser collects information about the different gases being emitted.

“It is a process that shouldn’t take more than 10 minutes. While your engine is running, the machine will record carbon monoxide levels and hydrocarbons if you have a petrol or CNG vehicle,” explains Dhawan. “For diesel cars, it records the smoke density levels.”

However, according to the audit conducted by the CAG, there were three main issues with the issuance of PUC certificates in Delhi—operators would issue certificates without recording the emissions, they would issue certificates within 1 minute of checking the car, and they would give pass certificates to vehicles whose emissions were higher than the required limit.

The CAG report found over 76,000 cases where a certificate was issued within 1 minute of the vehicle being brought in for checking. Just in the month of September 2019 itself, there were 7,643 cases where more than 1 vehicle was checked at the same centre at the same time.

“One centre only has access to one emissions analyser. It is impossible for them to check two vehicles at once,” argued Sirsa. “And so many certificates were issued within 1 minute of checking the vehicle. Do you think they’re actually testing the vehicle in this case?”

All data from PUCs is uploaded onto a central database, including the number of cars that are given certificates, whether they run on petrol or diesel, and what their recorded emission levels are.

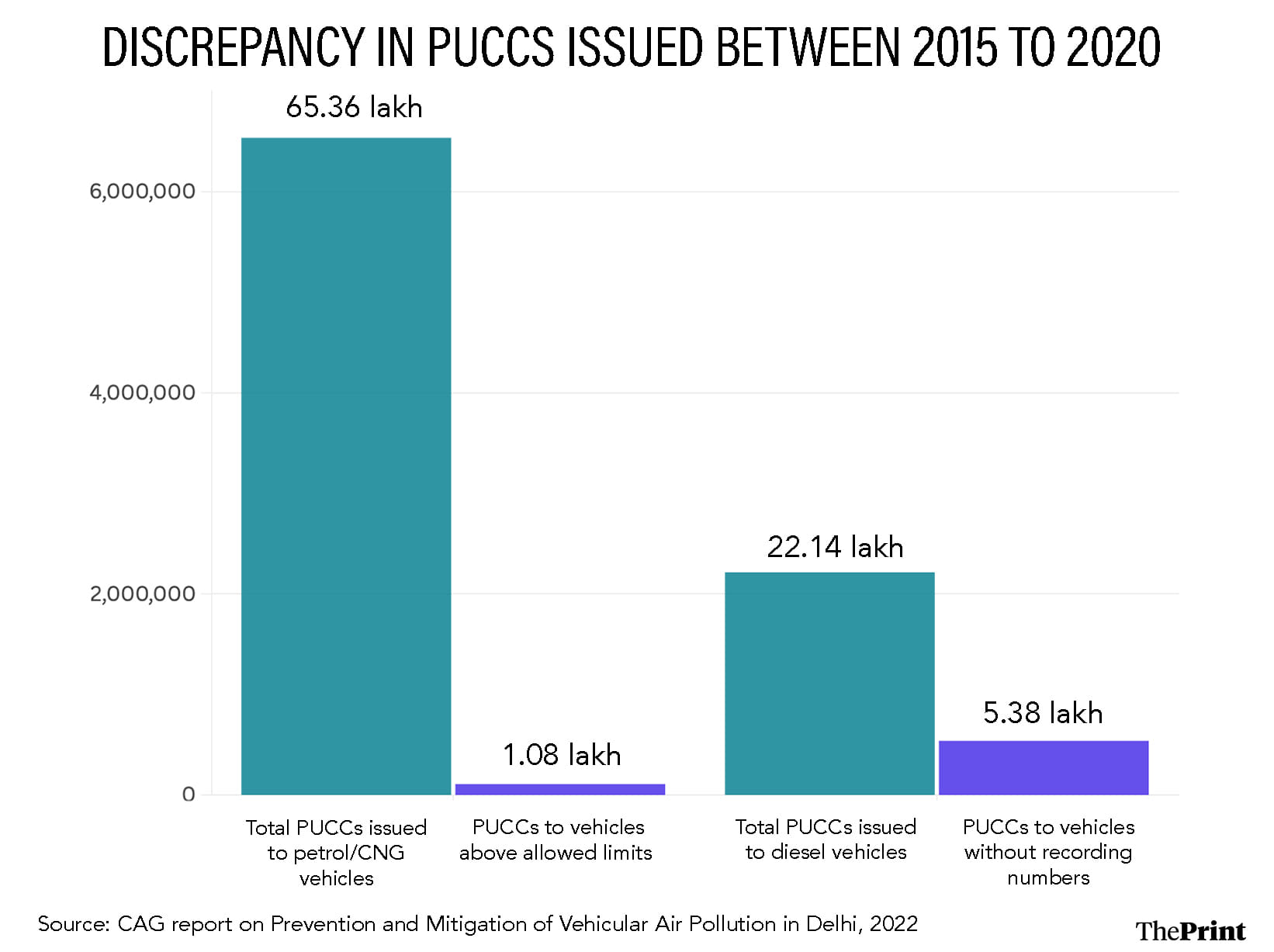

A total of 22.14 lakh diesel vehicles were checked across the five years, and 5.38 lakh of these passed their PUC certificate test with no recorded values. That means 5.38 lakh PUC certificates were issued to cars and bikes without even recording what their emissions were. Similarly, for petrol and CNG vehicles, over 1.08 lakh vehicles were given pollution certificates, despite their emissions being over what is permitted.

The issues highlighted in the report have been corroborated by Delhi residents who recall their own experience at PUC centres. Siddharth, a resident of Dwarka, said that when he went to get a certificate for his car for the first time, the operator didn’t bother with even checking his vehicle.

“He asked if it was BS-VI and then just gave me the certificate – I know it was a relatively new car, but I still thought he’d follow due procedure,” said Siddharth.

Bharat Stage (BS) VI norms are the current regulations followed by Indian manufacturers, which prescribe the emissions limits to be followed for vehicle manufacturing in the country. They were implemented in 2016 and are the latest in a set of 6 different standards, each more stringent than the previous one, aimed at reducing vehicular pollution at the production level.

Another resident said, on condition of anonymity, that when his carbon monoxide levels were higher than the permissible level, instead of asking him to get his car serviced the operator just used the numbers from another car on his certificate.

Inspection of PUC centres

Despite glaring irregularities in the working of PUC centres, Delhi’s transport department did not take any measures to inspect or monitor these centres through third-party interventions, the CAG report said.

Even though over 52,000 challans (fines) were issued to vehicles that were emitting smoke despite having a valid PUC certificate, Delhi’s transport department did not independently raise inquiries into the PUCs that were giving these certificates. The report mentioned that the transport department had no mechanism in place to internally inspect PUCs for quality of equipment and compliance to norms.

According to Sirsa, this lack of implementation of PUC certification and maintenance of PUCs had huge impacts on Delhi’s air pollution levels.

“If there are 1 lakh unchecked polluting vehicles driving on the road, imagine how high their emissions would be,” he said. “This is an entire breakdown of the PUC system.”

However, Amit Bhatt, the India Managing Director of International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT) explained that while PUC centres and operators do sometimes engage in malpractices, the problem runs deeper.

“Malpractice and implementation issues are definitely important, but the bigger question is whether the existing PUC system is enough for regulating air pollution,” said Bhatt. “The truth is, we need to overhaul the entire system.”

Larger problem with PUC system

In the way it is currently designed, PUC certificates are given by checking a vehicle’s carbon monoxide and hydrocarbons, or visible smoke levels, depending on the vehicle. While these are important parameters, they’re not the only pollutants emitted by vehicles.

According to Delhi’s Source Apportionment study conducted in 2018, vehicular emissions are responsible for 81 percent of the total nitrogen oxide (NOx) pollution in the atmosphere.

Nitrogen oxide is known to be harmful to pulmonary functions in humans beyond a certain limit. However, there is currently no mechanism to measure NOx emissions from vehicles, nor is it required under the current norms.

More importantly, PUC tests do not measure particulate matter emissions—PM10, PM2.5, or the more deadly PM1. Multiple studies link vehicular emissions to a rise in the air quality index (AQI) and PM2.5 concentration. An October 2024 study by the Centre for Science and Environment found that vehicles were the major contributors to Delhi’s air pollution, much higher than even stubble burning.

“We need to understand that these PUC tests were devised decades ago when the biggest air pollution problem was visible smoke,” explained Bhatt. “But now, we know invisible particulate matter is much more harmful, and we need methods to detect that in our vehicles too.”

Remote sensing an alternative?

A 2024 ICCT report on vehicular pollution in Delhi calculated emissions of vehicles on the road using remote sensing, which is a non-intrusive method of estimating pollutant levels of each vehicle.

Through remote sensing technology (RST), pollution is recorded without even needing to stop the vehicle, and multiple vehicles can be recorded at the same time. Unlike the gas analysers currently used by Delhi’s transport department, RST also calculates more parameters.

The report found that real-time emissions from vehicles in Delhi and Gurugram are sometimes as much as 14 times higher than the set limits and that methods like remote sensing would give the government a much more accurate picture of vehicular pollution.

“The fundamental issue with PUC tests is that they only record emissions when a vehicle is stationary. But the actual pollution would be much higher when the car is actually being driven in the city,” said Bhatt. “This is a problem that remote-sensing can possibly solve.”

Delhi’s transport department is also aware of the RST technology, which has been used in cities like Calcutta since 2009 to measure vehicular emissions. The CAG report also urged the transport department to adopt RST in the city.

However, the Delhi government has not set any date or timeline for this action.

(Edited by Sanya Mathur)

Also Read: Delhi’s vehicular fumes contribute 17% of air pollution Monday. Crop burning, no wind make it worse