New Delhi: Just six months ago, India’s aviation industry painted a rosy picture. Widely acknowledged as the world’s fastest growing aviation market, Indian skies were dotted with 670 planes in service, over 900 on order with both major manufacturers, airports were seeing a nearly 20 per cent year-on-year growth in passenger traffic, and international travel was also flourishing.

That was October 2018. May 2019 has brought with it a very different, desolate picture. One of India’s largest airlines — Jet Airways — has gone under, air fares have risen across the board, passenger traffic growth has plateaued at a mere 0.14 per cent, and dozens of new Airbus A320neo and Boeing 737 MAX aircraft have had to be grounded due to worldwide technical issues.

What went wrong? Did all this transpire out of thin air or were there bigger, long-term factors at play? Is this new trend reversible, or a death knell for the aviation industry in India? ThePrint examines several key factors at play to find the answers to these important questions.

ThePrint sent detailed questionnaires to both the civil aviation ministry and the DGCA, but received no response.

Also read: Wish Jet Airways reappears like a blazing sun, says founder-chairman Naresh Goyal

Rising fares are a symptom, not the disease

Skyrocketing fares have been a big factor behind the desolation in the aviation sector, and these are a byproduct of rising fuel prices and a paucity of seats due to planes being grounded for various reasons.

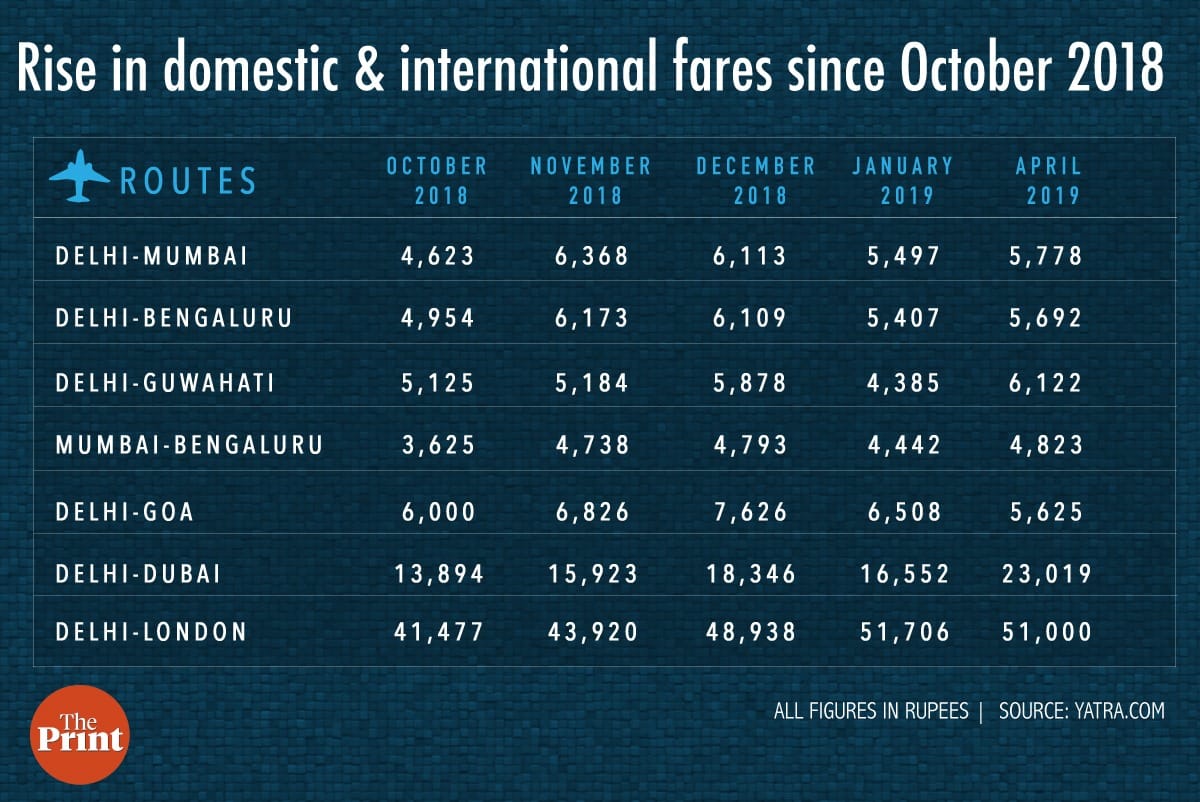

The fares across airlines — on a variety of trunk and non-trunk routes, such as Delhi-Mumbai, Delhi-Bengaluru and Delhi-Guwahati — have gone up by an average of Rs 1,000 in the last six months. International trunk routes like Delhi-Dubai and Delhi-London Heathrow have witnessed a hike of Rs 10,000 per ticket.

Aviation Turbine Fuel costs account for 31.2 per cent of the operating cost of the aviation industry. The growth in its consumption has been parallel to the increase in aircraft and air traffic movement — in 2016-17, for example, ATF consumption grew by 8.9 per cent.

But in the last six months, the price of ATF has fluctuated, putting further pressure on the industry. From Rs 74,567 per kilolitre (1,000 litres) in Delhi in October 2018, the price rose to Rs 76,378.80 in November, fell to Rs 58,060.97 in January 2019, before breaching the Rs 65,000 mark on 1 May. Air fares have followed suit.

In terms of capacity, six months ago, Indian carriers had an inventory of about 670 planes. Of these, about 200 have gone out of operation — some are grounded, others are down for maintenance. The grounded planes include Jet’s fleet of about 120 aircraft, 20 Boeing 737 MAXs and 35-40 Airbus A320/321neos, while 17 of Air India’s aircraft, including four Boeing 777s, are down for maintenance because the airline doesn’t have money for spare parts.

Ameya Joshi, founder of aviation analysis blog Network Thoughts, who was associated with Kingfisher Airlines and GoAir in the past, put the blame for the rising fares squarely on capacity constraints.

“There are certain places which have seen the capacity dip drastically to an extent where there is no connectivity or very little connectivity. Examples are flights from Mumbai to Rajkot, Mumbai to Aurangabad, Delhi to Nashik and a lot of sectors in the Northeast from where Jet Airways pulled out in February,” Joshi said.

“While airlines are redeploying capacity and trying to induct planes, not all routes are getting the capacity, thus affecting a certain section of passengers more than others,” he said.

Mark Martin, founder and CEO of aviation consultancy firm Martin Consulting, said: “The biggest impact on commuters is on account of rising air fares. People are not travelling because there are hardly any flights to travel. Indian aviation is in a very unfortunate state.

“Year on year, our fleet goes up by about 15 per cent because the demand is as such. Clearly, we are not seeing the demand now. It is a very alarming situation.”

But rising fares and falling capacity are merely a symptom, not the disease, experts say.

Nature of the market is the root of the problem

J.R.D. Tata, the pioneer of Indian aviation, had said in 1953: “Affordable fares are the bane of the aviation industry. The main causes of the losses are to be found not in high operating costs, but in the uneconomically low fares and mail rates and the crushing burden of fuel taxation imposed upon it.”

Tata’s words have proven prophetic time and again over the last 28 years, since privatisation took away Air India/Indian Airlines’ monopoly over India’s skies.

Industry experts have said in recent articles that the situation today has not been created in a few years — it has been inherent in the system.

Indian aviation has two kinds of airlines — full service carriers (FSCs), which offer amenities like food, better seats, entertainment system, frequent flyer mileage points etc., and low cost carriers (LCCs), which provide only basic transportation with no frills. Both chase the same customer, so full carriers’ fares have to be close to the LCCs’.

“The Indian aviation scene is largely choked by corruption across entities like Air India. Further, the cut-throat nature of pricing all for the sake of market share is not being monetised at all,” said Saj Ahmad, chief analyst at the StrategicAero Research. “While passengers have benefitted, the demise of Jet Airways highlights just how immature and inept the Indian aviation market really is.”

Ahmad also said that the pace of these developments was not a surprise.

“As a long-time critic of the overhyped Indian aviation market, I would say what we are witnessing now is the chickens coming home to roost. No one wants to invest in a market where yields are non-existent and aviation policy is, frankly, not worth the paper it is written on. For all the bluster around India’s economic growth, those in power simply have no idea what to do when it comes to aviation,” he added.

Ahmad also said that instead of appointing experts who know how to formulate strategy and open skies pacts, like in the UAE, India is festooned with “lethargy, red tape, apathy and corruption”.

“Until those are weeded out, casualties in the airline business in India will continue.”

Also read: Inside story of why DGCA is conducting a safety audit of Indigo’s A320neo Airbus planes

Low-cost carriers dominate the market

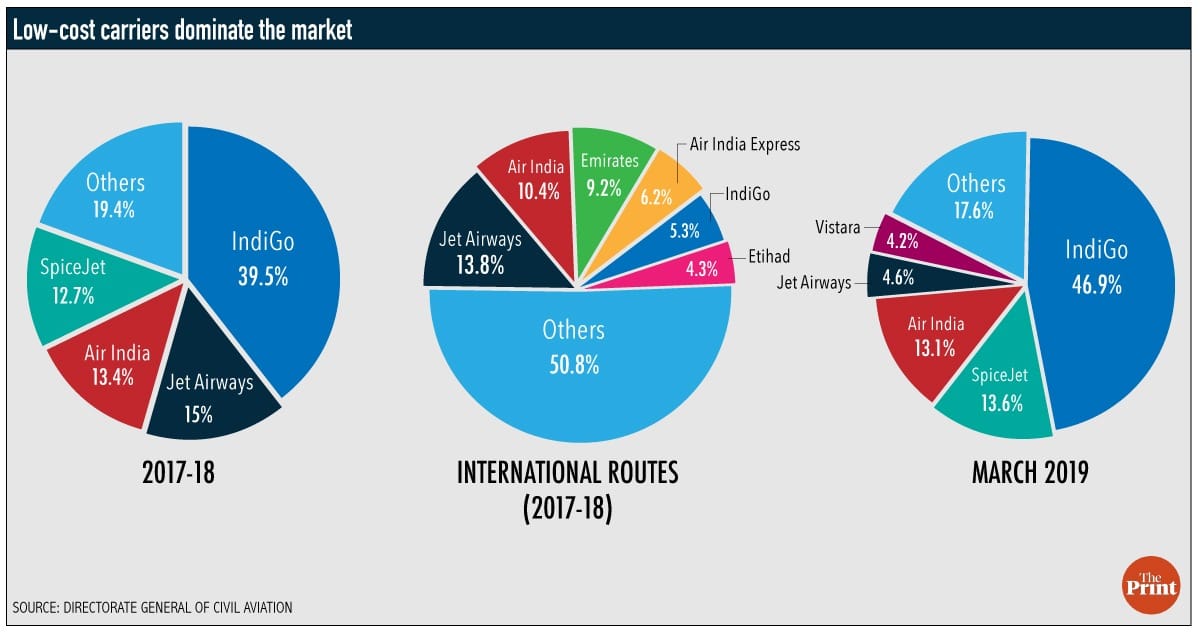

Market share: According to data from the Directorate General of Civil Aviation (DGCA), in 2017-18, IndiGo had the maximum market share (39.5 per cent), followed by Jet Airways (15 per cent), Air India (13.4 per cent) and SpiceJet (12.7 per cent).

On international routes, Jet had the highest market share (13.8 per cent), followed by Air India (10.4), the Dubai-owned Emirates (9.2 per cent), Air India Express (6.2 per cent), IndiGo (5.3 per cent) and the Abu Dhabi-owned Etihad Airways (4.3 per cent).

However, by March 2019, while IndiGo’s market share had risen to 46.9 per cent, Jet had fallen to 4.6 per cent, almost level with Air Vistara (4.2), which was launched just four years ago. SpiceJet and Air India had 13.6 and 13.1 per cent market share respectively.

Passenger load factor: In terms of Passenger Load Factor (PLF), a measure of capacity utilisation, SpiceJet is No.1 with 94.7 per cent, followed by GoAir (88.6 per cent) and IndiGo (88.2 per cent).

SpiceJet also topped the position in terms of scheduled international operations with a PLF of 89.4 per cent, followed by Jet Airways (83 per cent) and IndiGo (82.8 per cent).

Also read: Air India & Indigo fly without extra fuel for diversions, risky experiment say experts

Airlines have been in trouble for years

Jet Airways’ downfall: India’s oldest private carrier suspended its domestic and international operations on 17 April, owing to a lack of emergency funds.

Jet had been facing problems since 2007, when it bought Air Sahara and its ageing fleet. It hit a financial crisis in 2013, and was only bailed out by Etihad buying a 24 per cent stake in it.

The airline defaulted on loans and delayed payments to employees, pilots and even lessors. By March 2019, its debt had mounted to $1.14 billion (approx. Rs 7,900 crore), and needed at least $1.23 billion (Rs 8,500 crore) to get back its fleet.

The situation has put 23,000 jobs at stake, and has pushed up air fares on the 37 domestic and international routes that Jet was flying.

SpiceJet’s recovery: Nearly five years before Jet Airways’ problems, SpiceJet had faced a similar financial crunch that almost killed the airline. The DGCA had intervened, forcing the airline to suspend operations for a day, cancelling slots, and even preventing bookings beyond a month. However, the civil aviation ministry had stepped in and given it 15 days to find some money.

It was at that time that the airline’s founder, Ajay Singh, returned with a clutch of investors to bail out the airline and take back control from the Maran family of Tamil Nadu, which had initially bought a stake in 2010 and later taken control of it. He infused almost Rs 1,000 crore, cut staff, reduced routes and returned the airline to a semblance of respectability.

In the quarter ending December 2018, SpiceJet recorded a profit of Rs 55.1 crore, and Ajay Singh said at the time: “With a strong improvement in the macro cost environment and the increasing induction of the fuel efficient MAX aircraft, the outlook looks stronger than it has over the past year.”

Air India: The national carrier’s troubles seem everlasting, and it is only kept alive by injecting taxpayers’ money from time to time. Currently, Air India’s debt burden stands at about Rs 55,000 crore, and even civil aviation minister Suresh Prabhu had once said, “Air India is clearly a legacy issue. Its debt is unsustainable. Forget Air India, nobody can handle that debt.”

The airline’s troubles began when the international carrier (Air India) was merged with the domestic carriers Indian Airlines and Alliance Air in 2007. Since then, it has remained a loss-making enterprise.

The government has made attempts to disinvest Air India, without any results. Last year, it had even proposed to transfer the airline’s non-core assets and unsustainable debt to a special purpose vehicle to revive the debt, but to no avail.

The airline suffers from several performance issues — it ranks last in terms of punctuality, and had the highest number of cancellations and passengers who were denied the opportunity to board.

Blame on DGCA and ministry

Echoing what Ahmad said about India’s aviation policy, Amit Singh, former head of operations and safety, AirAsia, and the current head of training at IndiGo, blamed the Ministry of Civil Aviation and the regulator, DGCA, for the worsening situation.

“The last aviation policy we had was just four pages long. There has been no road map. The ministry is entirely responsible. What has DGCA done so far?” Singh said.

“There will be a time when an airline will be doing good and will boast about the profits, but the same airline will default in terms of salaries, debt etc. Nobody has a bird’s eye-view about what exactly goes on. During this Jet Airways debacle, other airlines — technically, as per DGCA rules — should not have made undue profits, but who was monitoring this process?”

Former Boeing 737 pilot and instructor Captain Mohan Ranganathan, however, said it was the ministry, not the DGCA, that should carry the can for this mess.

He alleged that SpiceJet was benefitting from the collapse of Jet Airways — in terms of getting first use of its planes and slots without any action — because of its political connections to the current BJP establishment.

“The DGCA is a mere clueless facilitator. It dances to the ministry’s tune, depending on the party in power. Earlier, it kept covering up and changing the rules and regulations to suit Air India, Jet and IndiGo. Now, SpiceJet is benefitting from rule-bending,” he claimed.

“In 2007, the ministry took total control of the sector, and qualification norms for the DGCA were tweaked to let the IAS lobby took control. This lobby messed up every aspect of aviation. The minister was controlled by crony capitalists, and the officials danced to the tune of the minister and the airline promoters. Audits, including financial audits, were a mockery and everything was swept under with false data.

“Now, banks have lost faith (except in the case of Air India, where they are arm-twisted by the government to dole out regularly, in spite of the blatant failure of the management on profitable operations), and airlines need cash for daily runs. Selling tickets in advance and at very cheap rates is easy money, but fatal in the long run. Jet is learning that the hard way.”

Also read: Air India now has 4 Boeing 777s grounded, because it doesn’t have money to maintain them