Pilibhit: Bharat Biswas doesn’t remember the exact date he came to India from Bangladesh. All he can recall with certainty is that then Prime Minister Jawahar Lal Nehru passed away three days after he and his family arrived from what was then East Pakistan.

Nehru, the first Prime Minister of Independent India, died on 27 May 1964. That was a bloody year for east India as well as Pakistan. In January, reports of a prized relic disappearing from a Srinagar mosque triggered attacks against Hindus over 2,000 km away in West Bengal and Bangladesh. Then Hindu mobs waded in too.

Amid the communal cacophony, thousands of Hindus poured into India from Muslim-majority Bangladesh. Bishwas’ family was probably one of them.

Bishwas and his family live in the Uttar Pradesh district of Pilibhit, which is home to an estimated 37,000 Bangladeshis, largely Hindus, who have crossed over to India over the years.

Situated on the border with Nepal, Pilibhit was in the news recently as Uttar Pradesh began implementing the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA).

The CAA seeks to give citizenship to non-Muslim minorities from Muslim-majority Afghanistan, Bangladesh and Pakistan who arrived in India before May 2014. The law is controversial, and the religious grounds it lays forth for citizenship have led to protests across India.

In Pilibhit, the CAA has brought much cheer among the refugees, who speak of a deep love for PM Narendra Modi. But a lot of confusion prevails too, as does worry that they might fail the test.

UP starts the count

The CAA was passed by Parliament in December last year. However, the rules of the CAA, which was notified in the gazette 10 January, are yet to be framed.

Even so, Uttar Pradesh has started implementing the law, asking districts last month itself to draw up a list of eligible illegal immigrants along a set format — their date of entry into India, which country they fled to arrive here, and the reason they did so.

It has been reported that UP subsequently provided a list of 40,000 immigrants from around 19 districts to the union home ministry. Around 37,000 of these are believed to be in Pilibhit alone.

Thousands of refugees who crossed over from Bangladesh in the 1960s and the 1970s were settled in Uttar Pradesh by the Refugees Relief and Rehabilitation Department, a government body created exclusively to tend to them.

After they had spent anywhere between two and 10 years in camps, they were rehabilitated across several districts, including Saharanpur, Rampur, Pratapgarh, Bahraich and Pilibhit.

In Pilibhit, which hosts the vast majority of these, there are at least four dedicated colonies for Bangladeshi Hindu refugees — Neoria, Gabiya, Ramnagra and Rampuria. Residents refer to it as a “mini-Bengal”, a home away from home for a displaced people.

As Biswas spoke to ThePrint, a group of young boys nearby was busy making an idol of Goddess Saraswati in preparation for Saraswati Puja later this month.

“We got our children to learn Hindi, mix with the culture of Uttar Pradesh. But we won’t let go of our own culture and traditions — we have created a mini-Bengal here,” Biswas said.

Also read: Citizenship Act will not be withdrawn despite protests, says Amit Shah

Love for PM Modi

The Pilibhit Lok Sabha constituency has been a BJP stronghold for several years now. Maneka Gandhi represented the seat for six terms before her son Varun took over in 2019.

The CAA initiative, say many refugees here, has deepened their support for the BJP, especially PM Modi, whom they admire for his acknowledgment of their “Bangla Hindutva pride”.

Ganesh Chandra Samudar arrived in India — West Bengal, to be specific — in 1952. After a decade-long stay in a refugee camp, he was settled by the Indian government in Pilibhit in 1962.

His home is a shrine to stalwarts of undivided Bengal, with framed pictures of Bengali litterateur Rabindranath Tagore, freedom fighter Subhas Chandra Bose, and spiritual leaders Ramakrishna Paramahamsa and Anukulchandra Chakravarty.

In one room, an image of Bose hangs beside a poster of PM Modi and Hindu monk Swami Vivekananda.

Samudar, 73, says he is grateful to the PM for the CAA, and hopes no one will abuse him as an “outsider” anymore.

He refuses to call himself a “refugee”. He was born in 1947, just before Partition, and he still identifies with the idea of ‘Akhand Bharat’, or undivided India, a reference to India as it was in 1947, comprising Bangladesh and Pakistan as well.

“I am not a refugee,” Samudar said. “I shouldn’t have to fight for my citizenship. I was born in Akhand Bharat and I will die here.”

‘CAA will secure identity’

Many refugees settled in Pilibhit already possess Aadhaar and ration cards, even voter IDs. Ask them how, then, will the CAA affect their day-to-day existence, and they say it is a matter of “safeguarding identity and rights”.

It’s important to them amid indications from the government, including from Home Minister Amit Shah himself, that Aadhaar and voter IDs don’t serve as proof of citizenship.

#EXCLUSIVE | Aadhaar Card cannot determine citizenship: Union Home Minister @AmitShah tells Navika Kumar at India Economic Conclave 2019. | #AmitShahOnIEC pic.twitter.com/Jkxj1DYSrv

— TIMES NOW (@TimesNow) December 17, 2019

It’s a claim Pilibhit district magistrate Vaibhav Srivastava also mentioned in conversation with ThePrint.

“Aadhaar card has nothing to do with citizenship. It isn’t citizenship proof,” he said.

Srivastava was referring to locals’ claims that the block-wise survey conducted to obtain information on refugees required them to show their Aadhaar number. The purported survey form was seen by this reporter but Srivastava pled ignorance.

“We don’t know where these forms are coming from,” he said, adding that the form circulated by the administration only asked for information on when the individuals arrived in the country.

Several refugees also told ThePrint that having a valid citizenship document will help them finally procure a caste certificate, which will then grant them access to reservation benefits.

They are hopeful that it will also help them get the five-acre land they were promised at the time of settlement but never given. “Many problems arise when refugees don’t have the required documents and this is why many didn’t get the land,” Srivastava said.

Also read: New swipe at CAA? Satya Nadella says nations without immigrants risk losing out

‘Still an illegal’

Sushil Baoli was 13 when he came to Kolkata, then Calcutta, with his parents during the 1971 Bangladesh Liberation War. After two years at a refugee camp, Baoli’s family was settled in Pilibhit’s Neoria colony. Baoli says he has all he needs, but continues to be seen as an “illegal” immigrant.

According to Baoli, the family lost their transit-related documents in floods, and thus can’t prove when they came here. But his claim to the country can’t be questioned, he added.

“The people who have grown up with me here in Neoria are my proof. That should be enough to show I have lived here all my life,” he said.

Even amid the pervasive optimism for the CAA, however, there’s much confusion about what exactly it entails.

“I heard Amit Shah say he will hand over citizenship to any non-Muslim who came from the three countries, that the government won’t even ask for any proof,” said Pradeep Kumar Chand, a resident of Neoria.

“But now, I am hearing we need to show our family history and other documents. This has left me very confused,” Chand added.

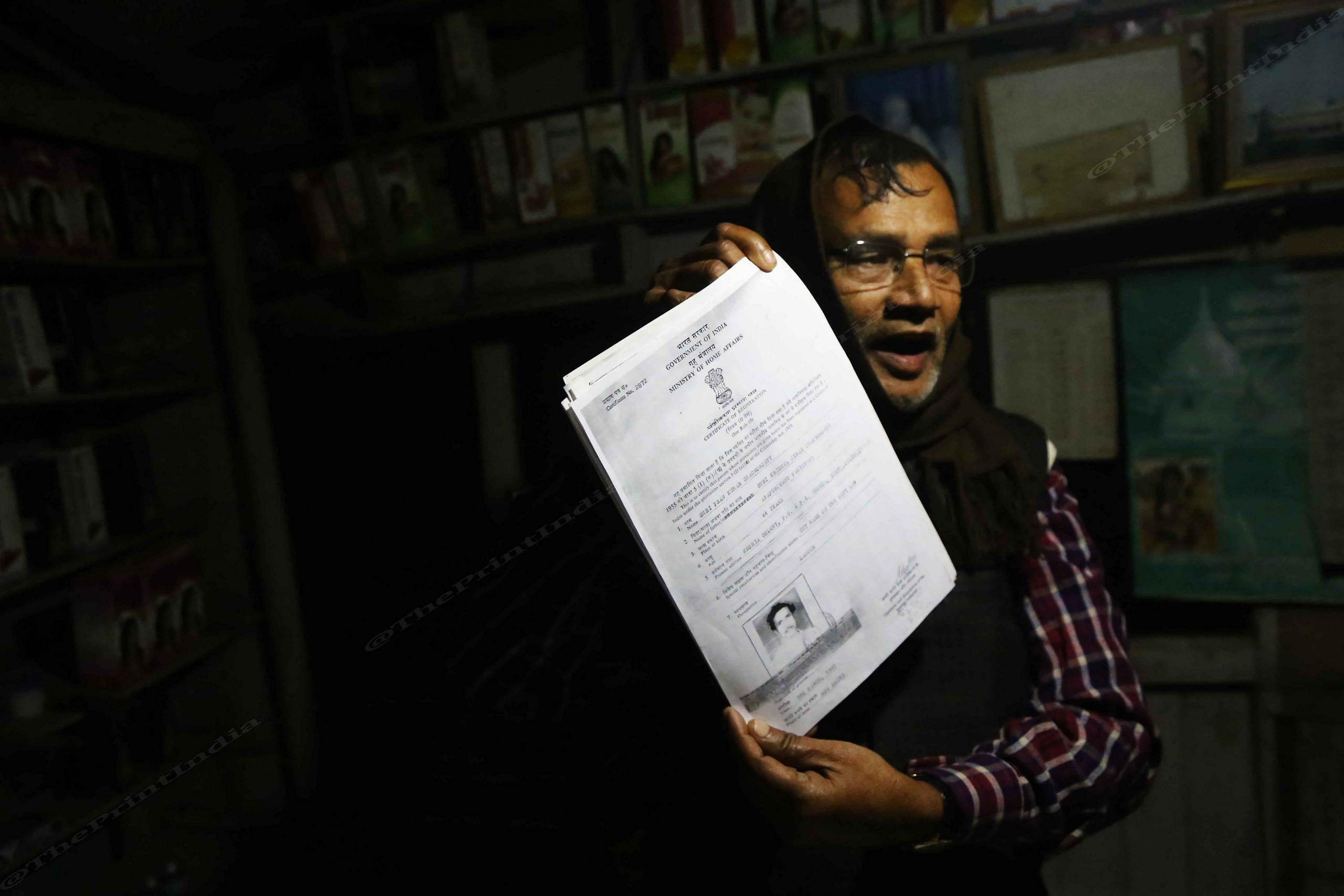

A similar worry stalks Biswas, who says he doesn’t have any document to prove he is an Indian citizen. He claims he doesn’t even have a border slip to account for his transit history.

His lack of documents, he fears, will render him ineligible for CAA.

‘Only a preliminary exercise’

The district administration began surveying the refugees residing in these colonies in the last week of December, before the CAA was even notified. But Srivastava defended the exercise.

“This is only a preliminary exercise we conducted for our own consumption, since we were aware just how densely populated Pilibhit district is with Bangadeshi refugees,” Srivastava said.

“If the law has been passed by Parliament, what bars us from conducting this exercise? There is nothing wrong or illegal about it.”

Also read: Supreme Court’s hearing-as-usual approach on CAA shows Indians need to go back to streets