In mid-April, Nuziveedu Seeds won a decisive battle against Monsanto in the Delhi high court. But its CMD Mandava Prabhakar Rao, a former ABVP general secretary, isn’t done yet.

New Delhi: Mandava Prabhakar Rao is a man on a mission. And how his mission ends could largely determine the future of India’s hybrid farm seeds, cotton and textile industries.

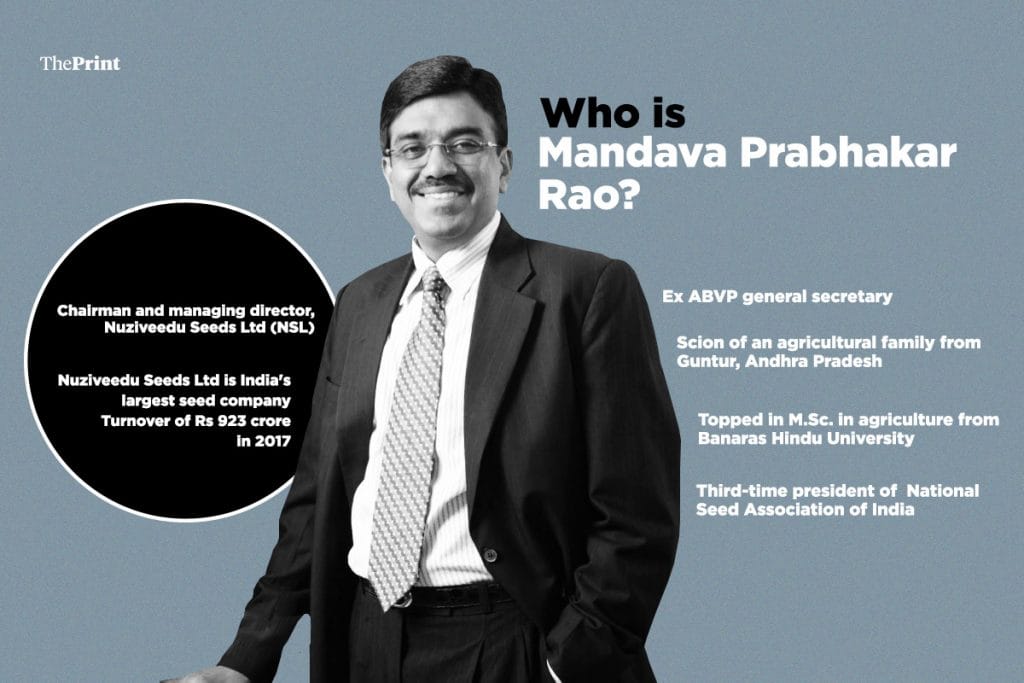

Rao is the chairman and managing director of Nuziveedu Seeds Ltd (NSL), a 45-year-old Telangana-based seeds company which claims to be India’s largest hybrid seeds firm.

He has an acute sense of being wronged, and apparently political connections that matter in the NDA dispensation at the Centre. And that was good enough for him to take on Monsanto, a multinational giant 100 times the size of his company.

In mid-April, Rao’s company won a decisive battle against Monsanto in the Delhi high court. Monsanto lost its patent on the coveted Bt technology, and, potentially, 80 per cent of its income from licensing of Bt cotton seeds.

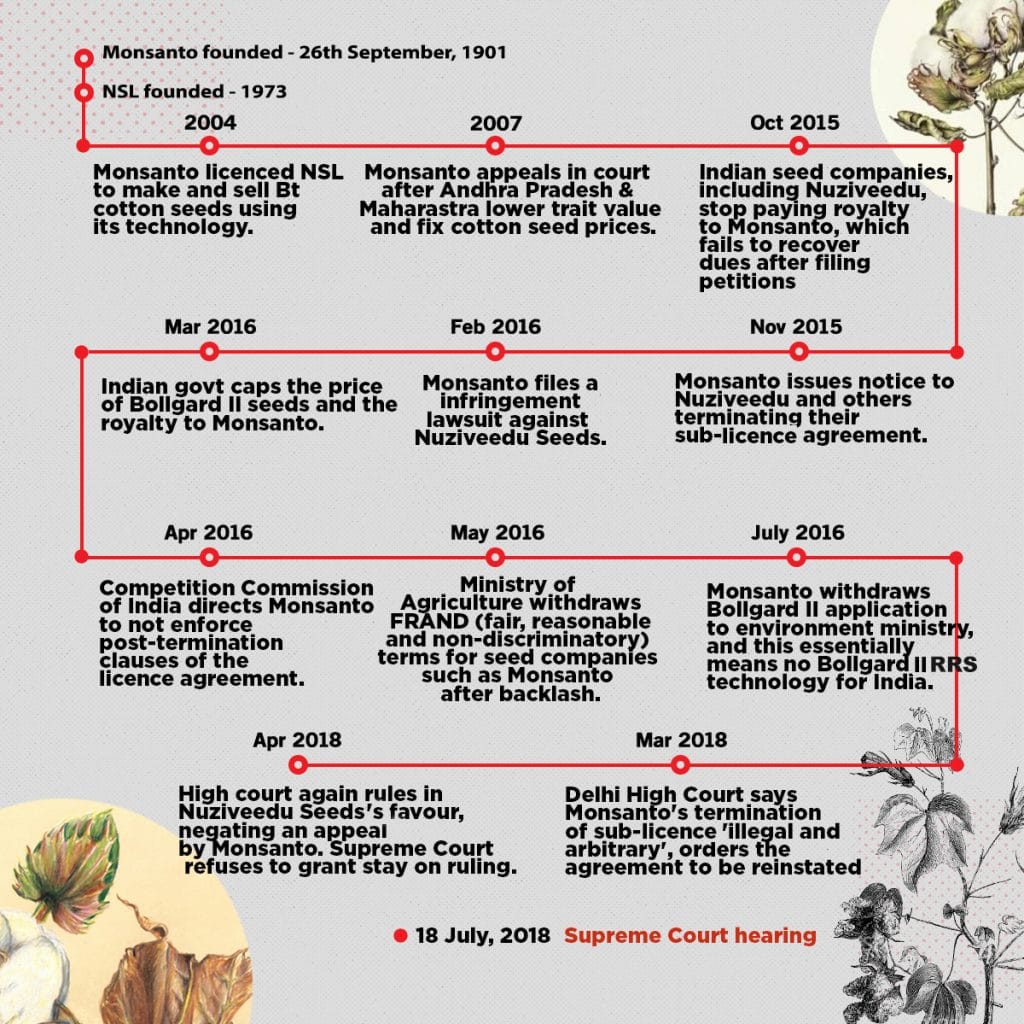

Monsanto has now approached the Supreme Court against the high court order, but the top court has refused to grant a stay on the ruling. The case is now being submitted for an expedited preliminary hearing on 18 July.

In declaring invalid Monsanto’s patent for Bt technology, the high court effectively made it possible for Nuziveedu and other seed makers to use the technology to make and sell seeds by paying much lower royalties, or trait fees as they are called — Rs 39 per packet, slashed by nearly 80 per cent from Rs 183.

India is the world’s biggest cotton grower, and Indian farmers use 45 million packets of hybrid Bt cotton seeds per year, of which 90 per cent are sold by Monsanto. Its earnings in the world’s largest market for cotton seeds could commensurately fall by 80 per cent to Rs 1,600 crore ($234 million) per year from Rs 7,400 crore ($1 billion).

Not content with his victory, Rao has vowed to continue the legal fight to have Monsanto return the entire amount of royalty that Nuziveedu paid it as a licensee, amounting to Rs 800 crore. His sense of having been wronged emerges from Monsanto’s past refusal to provide him additional discounts and cancelling its licence just as Nuziveedu was preparing for a high-stakes IPO.

Rao believes he is fighting a just battle. It helps that he is politically well-connected — a former general secretary of the Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad (ABVP), the student wing of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), Rao continues to be close to the ideological parent of the ruling BJP, it is believed. He is also said to have met BJP president Amit Shah ahead of a Delhi high court hearing, although Rao denies it.

Who is Mandava Prabhakar Rao?

Rao, 56, belongs to a well-off agricultural family from Andhra Pradesh’s Guntur district. Having topped his university in M.Sc., in agriculture, he joined the family-run NSL and has been managing it since 1982.

Today, NSL is one of India’s largest seed companies with a turnover of Rs 923 crore in 2017. It claims to have a 20 per cent share in the hybrid cotton seeds market in the country, and says half the cotton produced in India can be traced to genetic lines developed by NSL.

In 2004, US-based Monsanto, one of the world’s largest agrichemicals and agri-technology companies, licensed NSL to make and sell Bt cotton seeds using its technology, in exchange for a one-time fee and periodic royalties called “trait value”.

The license was renewed in March 2015, but the two companies were headed for war.

Rao has his reasons. Nuziveedu was in the process of rolling out an IPO, after having invested Rs 30 crore to expand its business when Monsanto cancelled the licensing agreement. “Monsanto derailed our IPO and started blackmailing us,” Rao told ThePrint in Delhi. “Our plans fell flat,” he said, “but I did not.”

Rao is not deterred by Monsanto’s size or economic clout — Monsanto’s net sales of Rs 94,900 crore in 2017 dwarf NSL’s Rs 923 crore.

Rather, he is said to be relying on his political connections. One of Rao’s close aides said he was in Delhi to meet Amit Shah when ThePrint caught up with him, but Rao denied this.

RSS bigwigs, and even the agriculture minister, told news agency Reuters in early 2017 that Rao had approached them for help against Monsanto. The RSS had said they would weigh in.

Intervening in favour of Rao would help the RSS strike a ‘swadeshi’ blow, critics say, regardless of the fact that Nuziveedu has received funding from American private equity investor Blackstone.

Last year, Rao was unanimously re-elected for the third time as president of the National Seed Association of India (NSAI), the country’s largest lobby of seed makers with more than 500 members. “His political connections help the association and its member companies in getting things done their way,” the owner of an NSAI member seed company said.

Rao, in his conversation with ThePrint, denied having received any support from the government. While he did not deny his association with the ABVP, he said, “There is no need for you to go by hearsay,” when asked about his connections.

In fact, Rao said, the government is in thrall of foreign companies. “The American embassy is campaigning inside the Prime Minister’s office. They have 50 people who are managing the PMO and press in India,” he said. “We fail to get an appointment despite repeated attempts but they meet PMO officials at their will.”

A battle over royalties

The history of the NSL-Monsanto confrontation goes back to 2007, when the governments of Andhra Pradesh and Maharashtra fixed the prices of cotton seeds while lowering the trait value that technology owners such as Monsanto could charge. Monsanto appealed against this order in the Andhra Pradesh high court which stayed attempts to fix trait fees by the state government.

In June 2015, Nuziveedu asked Monsanto to provide special discounts. “When denied, NSL executives told Monsanto and its Indian joint venture that there would be ‘consequences’ for refusing the discounts,” Monsanto wrote in a letter to the ministry of agriculture and farmer’s welfare.

Eventually, Monsanto terminated the agreement with Nuziveedu in November 2015, citing non-payment of dues by NSL.

Nuziveedu and some other seed makers filed a complaint with the Competition Commission of India (CCI), accusing Monsanto of abusing its dominant position in the market and forcing anti-competitive agreements on them. The union ministry of agriculture and farmers welfare simultaneously asked the CCI to look into Monsanto’s conduct, in an interjection that was seen to favour Indian seed companies. The CCI began an investigation.

In retaliation, Monsanto filed a suit in the Delhi high court, alleging that by continuing to sell seeds based on its Bt technology and using its trademark after the termination of their agreement, Nuziveedu had violated its intellectual property rights.

Meanwhile, the central government in March 2016 issued an order fixing the trait value of Bt cotton seed packets so as to ensure “uniform regulation across India for the sale price of cotton seeds with the existing and future Genetic Modification (GM) technologies,” prompting Monsanto to label India’s regulatory environment ‘arbitrary and innovation stifling’.

Things were clearly going in favour of NSL and Rao, and the high court’s April judgement cemented NSL’s victory.

The court agreed with NSL that the Indian Patents Act prohibits the grant of patents for plants, plant varieties or seeds. It did, however, give Monsanto three months to claim intellectual property rights in India by registering its Bt cotton seeds with India’s Plant Variety Protection & Farmers’ Rights Authority, which would allow it to protect its technology from being copied by unauthorised users.

But even before the court order, Monsanto had decided against introducing a new generation of cotton seed technology in India, citing unfavourable regulatory conditions. It had also said it could exit the Indian market altogether.

Reached for comment by ThePrint after the high court order, Monsanto said: “This judgment marks yet another milestone in what has become an increasingly unpredictable place to do business. The judgment is likely to have wide ramifications on many sectors and may negatively impact innovation.”

As for Rao and NSL, Monsanto said it would not comment on individuals.

Monsanto says it has amicably settled the dispute with other Indian companies — Ajeet Seeds, Kaveri Seed and Ankur Seeds — and wants to settle with Nuziveedu too. But Rao is on the warpath.

Destructive fight

NSL and Monsanto’s rivalry is bad news for India’s cotton and textiles producers.

The Bt technology, launched in India in 2002, is credited with increasing India’s cotton production threefold to 390 lakh bales in 2016 from 130 lakh bales in 2000. India’s cotton production recently surpassed China’s to become the world’s largest.

Driven by the growth in cotton output, India’s textiles industry has boomed. Its output doubled to 52 million spindles in 2017 from 26 million spindles in 2000.

In India, the textiles sector is the second-largest employer after agriculture, employing an estimated 32 million workers. The textiles ministry wants to double production, and trade to $300 billion by 2025, which will require a significant increase in the productivity and yield of cotton fibre (as well as more production of synthetic fabric).

Cotton seed makers say the target is impossible without the new generation of cotton seed technology.

“The target cannot be met without the latest Bt cotton technologies. The existing version is losing effectiveness against bollworms, which can wipe out crops,” said M. Ramasami, chairman of Rasi Seeds and a founding-member of the Federation of Seed Industry of India, which has 30 seed companies as members.

The dispute could end up destroying India’s exports, farmers’ income and job creation, agricultural economist Ashok Gulati warned. “If these ‘videshi’ companies were not bringing their latest products into the country, I am afraid to say that we would have become the largest importer of cotton in the world instead of the exporter,” he said.

India has failed to invest adequately in indigenous research and development, experts say.

“The total expenditure budget of Indian Council of Agricultural Research [an autonomous body responsible for coordinating agricultural education and research in India] is lesser than the budget of Monsanto, said Gulati. “Instead of blocking the flow of latest technology in India, we must pay the charges of using their technology.”

So.. Does bringing in ABVP, RSS help or ruin the cause of Indian seed Industry ???

Unnecessary discussion on political and social background , rather article should focus on real problems..

Why ABVP for heaven’s sake?

This is sponsored news to malign indian seed industry.

This article is half cooked story.