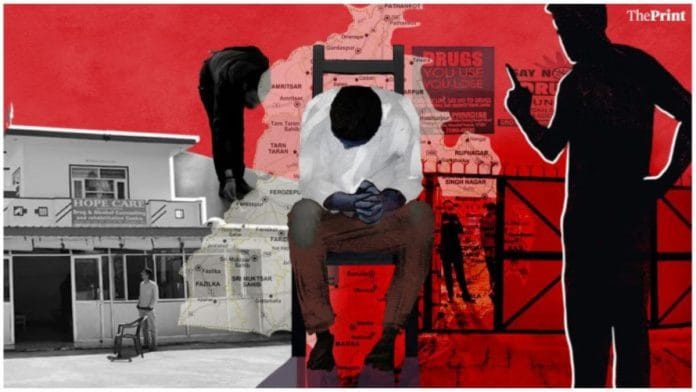

Chandigarh: When the Punjab government launched its Outpatient Opioid Assisted Treatment (OOAT) programme to wean addicts off dangerous drugs in 2017, there were great hopes it would provide a lasting solution to the state’s rampant drug problem.

But eight years down the road, the state cabinet has approved a complete overhaul of the programme—a key part of the state’s fight against drugs—after it was found to be marred by gross irregularities such as corruption allegations, missing stocks and diversion of addiction-control medicines.

Under the new system aimed at controlling distribution and curbing black market diversion, the government has capped at five the number of de-addiction centres—which double as OOAT centres—that a single private person can run in Punjab. This move will force the closure of multiple centres run by the same person, as 117 of the 177 private centres in the state are run by just 10 people.

OOAT centres provide a substitute drug combination, Buprenorphine-Naloxone (BNX), to people addicted to heroin, opium and their derivatives under the government’s opioid substitution programme to control substance abuse.

The Punjab Substance Use Disorder Treatment and Counselling and Rehabilitation Centres Rules, 2025, were finalised by the Department of Health on Thursday.

The new rules have also made biometric attendance of every registered drug addict “patient” in these centres compulsory to receive medication in a bid to weed out fake patient registrations and stop rampant pilferage and black marketing of the medicine.

Principal secretary for health, Dr Kumar Rahul, told ThePrint that the rules are expected to streamline the entire process of disbursal of buprenorphine to addicts, especially through private centres.

“Some issues had been cropping up on a regular basis, which we expect to be ironed out,” he said, adding that multiple centres have been given six months to shift patients to other centres.

“Our primary aim in running the programme is to keep addicts away from dangerous drugs through a harmless substitute. Though ideally, weaning them away from all drug abuse should be the long-term goal,” Dr Rahul added.

Since the programme’s launch, the government has set up 547 government OOAT clinics and another 177 licensed de-addiction centres run by private people in Punjab. Between them, more than 10.31 lakh registered addicts are given a daily dose of the combination drug.

While the medicine is free in government centres, a single tablet can cost between Rs 25 and Rs 40 in private de-addiction centres. If illegally diverted to the open market, each tablet can fetch Rs 300.

Despite reports of private centres charging exorbitantly for the medicine, the new rules have not capped the price of the tablets.

Moreover, despite reports of irregularities and low recovery rates, the government hasn’t ordered a systematic audit of the effectiveness of the substitution strategy either.

In March 2023, health minister Dr Balbir Singh said that between 2017 and February 2023, only 1.4 percent of registered patients had recovered in government-run centres, while 0.47 percent of the patients in private centres had completed their treatment.

Also Read: ‘Udta Haryana’ in areas bordering Punjab — ‘situation grim’ as drug addiction tightens grip on youth

Rampant drug use

Punjab has been battling a massive drug crisis for the past decade. A 2016 statewide survey by the Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research (PGIMER) in Chandigarh estimated that 15.4 percent of Punjab’s population was engaged in some form of substance use.

According to the latest National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) report released this month, Punjab recorded the highest number of drug overdose deaths for the second consecutive year in 2023, with 89 fatalities.

On 1 March, the state launched a massive drug control drive titled ‘Yudh Nashian Virudh’, or War Against Drugs, centred around a three-pronged strategy—Enforcement, Deaddiction and Prevention (EDP).

More than 34,000 people have been arrested since the beginning of the drive, in over 23,000 cases. More than 1,500 kg of heroin has been recovered since the beginning of the drive and almost 40 lakh pharmaceutical tablets have been recovered.

The drug substitution strategy through OOAT clinics was introduced during the Congress government under the then chief minister Capt Amarinder Singh.

The aim was to wean drug users off life-threatening substances like heroin, known as chitta, and other opioids by substituting them with BNX, which is considered a safe substitute.

Addicts were encouraged to register with government centres and licensed private centres from where they would get BNX according to their daily requirement in an outpatient setting.

BNX is a controlled drug and not available on the open market.

The Punjab government procures it annually from manufacturers based on requirement estimates. Only licensed private centres can procure the drug directly from manufacturers.

Distribution to patients from all the centres was to be strictly controlled through an online centralised monitoring system.

Despite the safeguards, over the years, the programme ran into several controversies, including BNX manufacturers running multiple private centres, missing tablets and their sale in the open market.

Diversion of BNX from private centres

One of the most prominent cases involved a Chandigarh doctor, Amit Bansal, who was arrested in January for malpractice at the de-addiction centres he owned. At the time of arrest, Bansal was running 22 private de-addiction centres across 16 districts in the state.

The Vigilance Bureau issued a press statement on 1 January, following Bansal’s arrest, saying that the medicines allotted for his centres were being sold in the open market at inflated prices to people who were either not on the rolls of these centres or were registered under forged identities.

The Vigilance Bureau spokesperson added that another case had been registered against Bansal’s employees by the State Task Force on drug control in Mohali in 2022, following allegations of diversion of BNX.

Another FIR was registered against Bansal on the same charges under the Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances (NDPS) Act in June 2023 in Nakodar in Jalandhar. The Vigilance Bureau said that even though the centre’s license had been suspended, he managed to get the matter “hushed up” through health directorate officers/officials.

It added that another FIR was registered against Bansal’s employees in November 2024 in Patiala, again for diversion of BNX from the centre for sale in the open market.

Following the Vigilance Bureau case, the government cancelled the licences of all the centres run by Bansal, and a wider probe was launched. Bansal remained in jail till March, when he was granted bail.

But in April, the Patiala police booked Bansal under the Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances (NDPS) Act after a health department probe panel found that one of his centres in Patiala sold 26 lakh BNX tablets between 1 April and 13 November 2024, even though it had only 55 registered patients at the time. The report added that sales of over 31,000 BNX tablets were unaccounted for.

The Enforcement Directorate (ED) initiated an enquiry against Bansal based on multiple FIRs against him. In July, the ED raided several locations in Punjab and some in Mumbai as part of the investigation. The same month, the ED attached Bansal’s properties worth Rs 21 crore.

While Punjab police have filed untraced or cancellation reports in the 2022 and 2023 cases, an inquiry by the health department is underway against Bansal.

Also Read: Punjab’s war on drugs is an asymmetric fight. Poor infra, not enough doctors or data

Same manufacturers and suppliers

Following Bansal’s arrest in January, the then Vigilance Bureau chief, Varinder Kumar, wrote to Chief Secretary K.A.P. Sinha, expressing fears about the monopolisation of the entire BNX supply chain by a handful of private operators.

“It has come to notice that most of such centres are owned/managed by a few persons and they have turned them into a lucrative private enterprise/syndicate just to enrich themselves,” he wrote.

“Owners of many such centres have established their own drug factories as well and they are supplying these medicines/tablets to their own and other drug de-addiction centres. Moreover, it has been learnt that the tablets are sold in the black market as well,” he added.

Kumar also provided a list of those with more than one addiction centre in Punjab: Bansal was running 22 centres in Punjab, the highest in the state, while another distributor, Rohit Takiar, was running approximately 21 centres and had his own drug factory in Gujarat. Similarly, the Mahajan group in Pathankot was running 11 centres and also had a drug factory in Gujarat.

“These drug de-addiction centres have been turned into a business venture by a few persons for personal profit, thus defeating the real purpose of the state government behind grant of licences to these centres,” the Vigilance Bureau chief wrote to the chief secretary.

“In the light of the above, it is suggested that the conditions/rules for grant of licences for running a drug de-addiction centre may be relooked into to avoid any kind of manipulation by the persons with vested interests,” he added.

Not standard quality, pilferage

The quality of BNX and the diversion of tablets were big challenges.

In October 2018, an internal health department inquiry found that the BNX being supplied to de-addiction centres in Punjab contained up to 25 percent more of the active ingredient than legally permitted. Two of the four major buprenorphine suppliers were found to exceed the limit, while one was below the dose limit.

The government declared these medicines below standard and the then additional chief secretary Satish Chandra recommended the suspension of their supply.

“Under the new rules, checking of the quality and potency of the drug would be a regular requirement,” Kumar Rahul told ThePrint.

Over the years, the diversion and pilferage of BNX tablets from these centres has been a recurrent problem.

Last week, BNX worth Rs 7 lakh was stolen from the Civil Hospital in Punjab’s Moga. In August 2018, the Food and Drug Administration raided a wholesaler in Ludhiana and seized 1.6 lakh tablets of the Buprenorphine-Naloxone combination stored illegally.

In November 2019, the then Punjab Health Secretary Anurag Aggarwal issued notices to 23 private de-addiction centres and a pharmaceutical company, seeking an explanation for over 5 crore missing BNX tablets from these centres.

However, the then health minister Balbir Singh Sidhu dismissed Aggarwal’s actions as baseless and “biased”, saying they had “caused an embarrassment to the government”.

Despite the clean chit given by the minister to his department, the case of the missing BNX pills snowballed into a major political issue in the state, with the opposition using it as an election plank in 2022.

(Edited by Sugita Katyal)

Also Read: Is ‘Ice’ becoming the new ‘chitta’? Hit hard by Taliban’s opium ban, Punjab is breaking bad