In India, spacing between births for women aged 15-29 years worsened from 25 months to 22.5 months over 10 years.

New Delhi: Indian women aged 15 to 29 years and those with more years in school gave birth at shorter, unsafe intervals over the decade to 2015-16, shows an IndiaSpend analysis of health data.

Birth intervals–the time between two successive live births–of less than 24 months may lead to low birth weight and death of a child, according to the 2015-16 report of the National Family Health Survey (NFHS).

The optimal birth interval to reduce neonatal and infant mortality is three to five years, according to global research (here and here). In India, spacing between births for women aged 15-29 years worsened from 25 months to 22.5 months over 10 years, we found.

The median interval between two live births fell by 2.5 months to 22.5 months in 2015-16 from 25 months in 2005-06 for women aged 15-19 years and by 6 days to under 29 months from 29 months for women aged 20-29 years, according to our analysis of data from 2005-06 and 2015-16.

“It is difficult to comment without looking at disaggregated NFHS data, which has not been released yet for 2015-16,” said a New Delhi-based demographer, requesting anonymity. “We will need to look at how many of the earlier born children to women in the 15-19 age group were alive or dead and then check for confounding factors. With India’s high neonatal mortality rate, it is possible that median birth intervals in younger women have gone up among those whose children died soon after being born.”

The legal age for marriage in India is 18 for women and 21 for men. Underage marriages, especially of girls, rose in urban India–one in five girls between ages 10 and 17 in urban areas was married in 2011–and while the immediate reasons were not clear, patriarchy and the continuing hold of tradition are implicated, as IndiaSpend reported on June 9, 2017. By age 22, 56% of women were married, according to an ongoing global study of childhood poverty in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, IndiaSpend reported on November 17, 2017.

Overall, the median gap between successive live births rose by 27-28 days for women aged 15 to 49 years.

Women with highest education levels was the only group that saw birth intervals worsen by 24-25 days to under 36 months in 2015-16 from 36.5 months in 2005-06.

Only women in the poorest 20% households gave birth at shorter intervals in the decade to 2015-16, with the median gap worsening by 15 days to under 31 months from over 31 months.

Families are smaller, but they want at least one son

A higher share of Indians in urban areas and with higher years of schooling reported a preference for sons in the decade to 2015-16.

While the share of women with up to five years of schooling saying they preferred more sons than daughters fell by over 2 percentage points, it rose by 1-3 percentage points for those who spent eight or more years in school.

Among men, while the share of those with up to five years of schooling saying they preferred more sons fell by up to 4 percentage points, it rose by up to 3 percentage points among those who spent eight or more years in school.

In urban areas, a higher share of men and women said they wanted more sons than daughters. While the number of urban men preferring a son rose by 3 percentage points to 16.4% in 2015-16 from 13.6% in 2005-06, that of urban women wanting more sons increased by 0.2 percentage points to 14.2% from 14%.

“Essentially, you are talking about the interval between second and first birth or third and second birth (may be very few cases),” said Rajib Acharya, associate at the India branch of the Population Council, a think tank. “With rising age at marriage, this group of girls aged 15-19 consists of more disadvantaged girls in 2016 compared to 2006. So, it is not unusual if you see a decline in birth interval over the years.”

“As for reporting of the desire for more sons than daughters is concerned, I am not again surprised by the increase among more educated women,” said Acharya. Fertility has “considerably declined” among this group, he explained, and is now less than replacement level–2.2 children per woman–or the stage at which populations stabilise.

The normative preference–Indians still believe having a son is better than a daughter–for sons is still same, argued Acharya. Family sizes are falling, but it is more likely families want at least one son. “Hence you see a slight increase in son preference among those who reside in urban areas or those who are educated beyond a certain level,” he said.

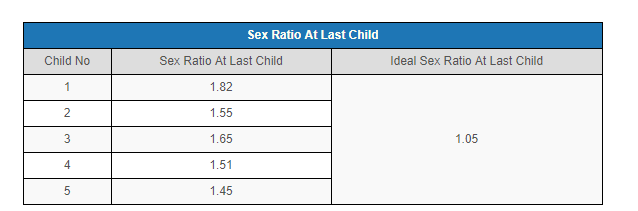

India’s sex ratio for first-borns was 1.82 boys for each girl and for fourth-borns 1.51 in 2015-16, compared with the ideal of 1.05, according to the Economic Survey 2017-18.

This article was first published on Indiaspend.org on 29 March 2018.