New Delhi: On a pavement next to Delhi’s Bangla Sahib Gurdwara, people snuggled into their blankets on a cold Delhi winter night.

There’s a night shelter barely five minutes away, but they’d rather stay where they are for a host of reasons: Some have been turned away from shelters for want of an Aadhaar card, while others fear the jostle for space. Others still are disillusioned by promises that aren’t fulfilled.

“I prefer to sleep out in the open,” said Bajrangi, one of the many people sleeping outside Bangla Sahib. Others sleeping not too far echo the sentiment.

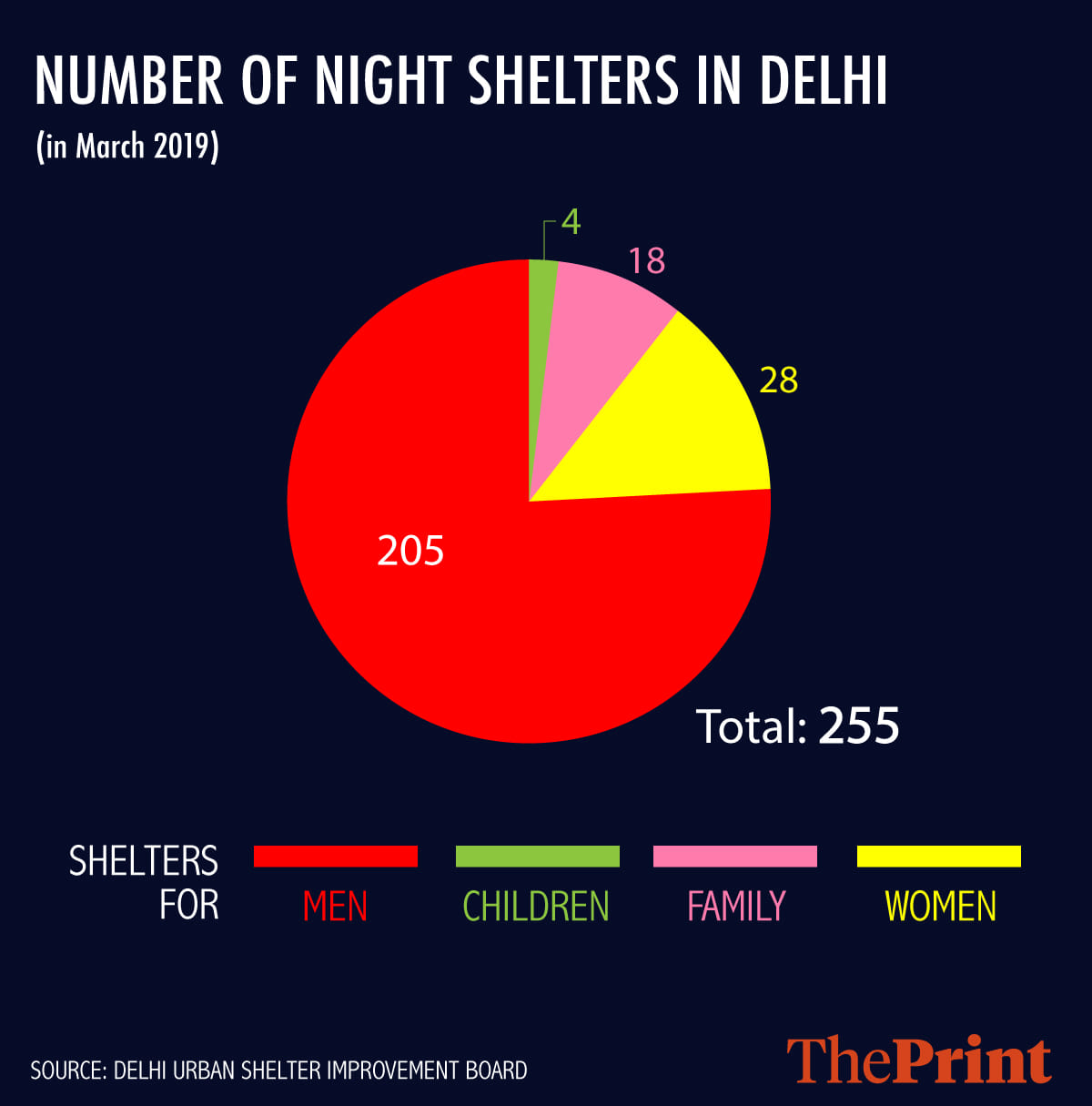

Even at full capacity, Delhi’s 255 shelters are ill-equipped to handle the national capital’s homeless hordes. According to the Census of 2011, Delhi had a homeless population of 47,076, but NGOs peg the figure at around 2.5 lakh.

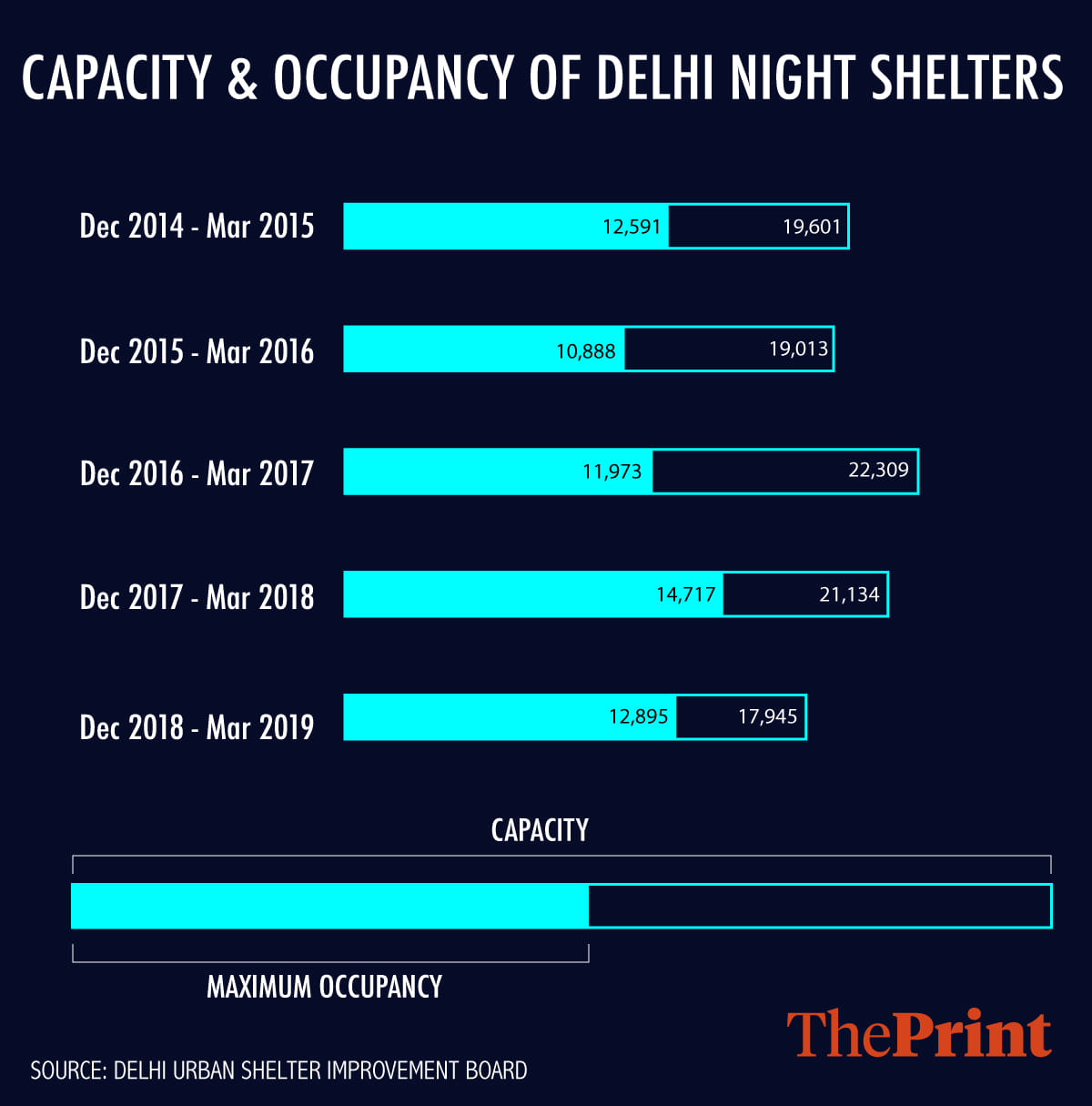

The capacity of night shelters as of March 2019, according to the Delhi Urban Shelter Improvement Board (DUSIB), is 17,945. Even so, only 12,895 people are currently residing in shelters, according to DUSIB senior engineer N.H. Sharma.

“It really depends on the area and the temperature, but often shelters do not fill up to full capacity,” he told ThePrint.

When the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) came to power in 2015, Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal ordered additional night shelters, along with over 30,000 blankets, and more than 10,000 durries and jute mats. They also launched an app where one can report homeless people in need of help.

However, occupants say shelters often lack basic amenities, adding that overcrowding in the accommodations around central Delhi often leads to scuffles.

Doctor visits are mandated, but rarely take place, said Sunil Kumar Aledia, the chief executive officer at Centre for Holistic Development, an NGO that works for the inclusion of homeless people into society.

According to Aledia, clean drinking water is not always available, and despite the fact that night shelters are mandated to provide food under the Deen Dayal Antyodaya Yojana, which is meant to uplift the urban poor, it is often not.

Out to help

Every winter night, at least 16 rescue teams, mostly from NGOs like the Society for Promotion of Youth and Masses (SPYM), drive through the city to rescue the stranded.

Whenever they encounter someone on the side of a road, they check to see if they can be relocated to a night shelter.

Swapan Das, a labourer from Assam, woke up reluctantly as a rescue team approached him one night this February, offering him shelter at a nearby location.

“I already tried to go there, but they turned me away,” he told them. “They wanted my Aadhaar card, and I don’t have one.”

Swapan isn’t the only one who has faced this problem. According to Aledia, the problem is rampant across the city.

“The people around Tilak Nagar face the worst of it, many of them have complained about this,” he told ThePrint.

But according to the authorities, no such identification is a prerequisite to avail of shelter. “We ask for identification for the sake of emergency,” said Rajesh Pandey, a caretaker at the night shelter outside Lok Nayak Hospital at Delhi Gate.

“Sometimes police come in looking for people, it helps in such situations. But it is not mandatory,” he added.

When the rescue team took Das back to the shelter he was turned away from, Das was let in, even as the caretaker insisted that his superiors had directed him to log the Aadhaar details of occupants.

A member of one of the rescue teams trawling Delhi’s roads said the number of calls they got from DUSIB — which itself is notified about the homeless by good samaritans — varied from night to night: From 40 one day, to four on another.

The team, which usually comprises two women and two men, often comes across people who don’t want to go a shelter with them, some are suspicious, while others just refuse to move.

Vickky Sharma, a rescue coordinator who runs one such team, said he could now predict who will, and who will not, accompany him to a night shelter. He continues to drive around town, keeping an eye out, especially for people who are unconscious — the ones they call “natural rescues”.

“If we leave them behind, they’ll be dead by morning,” said Vickky.

Also read: Uttar Pradesh Dalit families left homeless by ‘mysterious fire’ start hunger strike

‘I like my space’

Outside a night shelter at Fatehpuri, Kishore, 20, has stacked up some cardboard for protection against the cold. Asked why he doesn’t move into the shelter, he looks aghast.

“I have seen people sleep on top of each other in there. I like my space,” he said.

He can’t help but laugh at the thought of going in. “Do you know how often they get into fights? Please let me be where I am,” he added.

Talking to ThePrint, Meena, who lives near the Nizamuddin flyover, said she preferred to snuggle up next to the fire she builds every night. The women “in there stole my belongings”, she said, adding, “At least, outside, I know how aware I need to be.”

But the lack of facilities are not the only factor. A crucial detriment to occupancy, say experts, is location. According to Aledia, the shelters in central Delhi are far more overcrowded than those on the periphery.

“That is why the government says they are not filled to their full capacity,” he told ThePrint.

Asked why more shelters were not built in central areas, a DUSIB official said land availability remained a problem.

The family tree

Of those who do choose to stay at shelters, many are either women or families, drawn to the closed walls for the obvious safety factor.

For 60-year-old Suman, the shelter is the safest space she has lived.

“Sure, there were problems three-four years ago, but now they have built walls and reinforced them with barbs,” she added.

Bilal, a caretaker at the shelter near Bangla Sahib, said there used to be incidents of drunk men troubling women at the shelter, but that was “over five years ago”.

In shelters for families, a sense of camaraderie pervades. Meena, who hails from Nepal, first came to Delhi with her mother when she was barely six years old. Her mother worked as domestic labourer, and Meena joined her, eventually taking up the same job. They moved to Raja Ovara, a slum area in the capital, but it was demolished by the government in 2010.

Meena, now 30, lives in the Bangla Sahib night shelter, with her husband who is paralysed below the waist and begs at India Gate for a living, and their four children. “I am happy here,” she told ThePrint.

Urvashi, her mattress neighbour, has also been living in the shelter for over two years now. Her four-year-old daughter Maruti is best friends with Meena’s daughter Pari.

She shuddered as she remembered the time her family spent sleeping on the road. “At least now I have a roof over my head,” she added. For meals, she said, they went to the gurdwara next door.

Also read: What the girl in the pink burkha taught me about life and loss in Old Delhi

‘Vested interests’

Mohammed Harum, who has lived at the Delhi Gate shelter for more years than he can remember, said his biggest grievance was that the shelter promised a TV but it turned out to be broken.

“It plays nothing,” he said, adding, “Even the water machine doesn’t work. It gives electric shock.”

His fellow occupant Prithviraj, however, said the shelters had improved considerably over the past seven years.

Bilal, the caretaker at the shelter near Bangla Sahib, said those who chose to sleep outside the gurudwara had vested interests.

“At night, people donate blankets and food. They wake up in the morning and sell them,” he added. “That’s why they don’t come in.”

Honorless, heartless, brainless, worthless CM of Delhi must resign