New Delhi: In 1987, Amir Subhani topped the IAS examination. He retired last year as the chief secretary of Bihar, and other than for a brief period of five years between 2000 and 2005 when he served as a director at the Centre, Subhani never got deputed to Delhi.

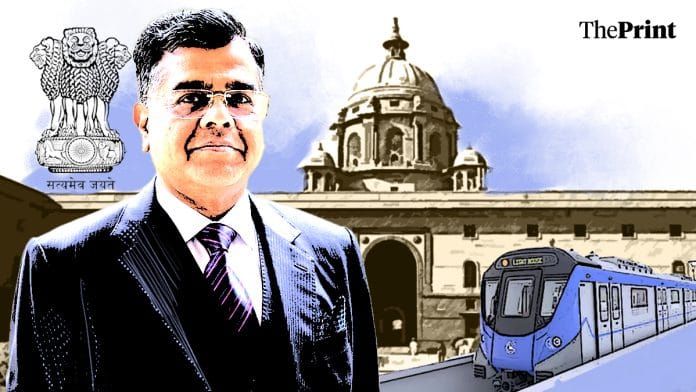

His batchmate, who got the second rank, has been one of the primary anchors of the country’s national economic policy for at least the last five years and is currently the topmost civil servant in the Government of India—T.V. Somanathan.

Somanathan was appointed the cabinet secretary for two years in August last year.

While he may have failed to top the examination, within months, he was awarded the gold medal for the best IAS probationer of his batch. The standard for his career as a civil servant for almost the next forty years was set.

As a civil servant, Somanathan, a Tamil Nadu cadre officer who holds a PhD in economics, has been more of an ‘economist’ than a ‘generalist’ right from the beginning of his career.

From starting the Chennai metro back in the early 2000s to returning to the city to implement the Goods and Services Tax regime of the Modi government in 2019, Somanathan’s contributions have been significant, both, to his state cadre at the Centre.

Indeed, while most books written by IAS officers are typically post-retirement tell-alls about their careers, the books written by Somanathan are more academic in nature, published by the likes of the Oxford University Press and Cambridge University Press.

Most of his colleagues admit that an academic expert of his kind is rare in the civil services and that Somanathan stood out in the field even in his early days. Of course, to begin with, as a chartered accountant, Somanathan had a successful career even before becoming a civil servant.

Also Read: Age just a number & retirement a formality. How retired IAS officers continue to run Modi govt

Straight to the state secretariat

Unlike most IAS officers who are posted as district magistrates in the early years of their career, Somanathan never served in this key administrative position. Instead, after serving as sub-collector for two years from 1989 to 1991, he was directly moved to the Tamil Nadu secretariat’s finance department—a sector that has become his area of expertise since then.

After serving as deputy secretary for four years in the finance department, where he oversaw the state’s budgeting process, he went on to become an executive director of the Chennai Metropolitan Water Supply and Sewerage Board (CMWSSB). Here, he sought to align the board’s operations with broader municipal and state policies, ensuring that Chennai’s water and sanitation infrastructure could scale up.

He then went on to serve as a Joint Vigilance Commissioner before moving to the World Bank for five years through its Young Professionals Program.

In 2000, he became one of the Bank’s youngest sector managers in the Budget Policy Group. In 2001, Somanathan served in a number of positions in the state secretariat before moving to Chief Minister M. Karunanidhi’s office as his secretary for two years—a posting which would add the art of political manoeuvring to the officer’s skill set.

Here too, his significant contributions were in the economic sector, including facilitating politically sensitive decisions, such as implementing increases in power tariffs, which were crucial for the state’s fiscal health and energy sector sustainability at the time.

Over a decade later, in 2011, he returned to the World Bank for a period of four years.

Chennai’s ‘metro man’

His next significant posting in the state came in 2007 when he was appointed as the managing director of the Chennai Metro Rail Corporation (CMRL), whose foundation he laid.

In this position, Somanathan played a crucial role in achieving financial closure and subsequently awarding the initial tenders for implementing the ₹14,600 crore Chennai metro project.

In 2010, he came to the Centre for the first time on deputation to serve as the joint secretary in the Ministry of Corporate Affairs, but in less than a year, he went to Washington, D.C. on the World Bank’s request.

After completing his stint at the World Bank, in 2015, Somathanan came back to the Centre to Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s PMO—an association that has lasted for over a decade since. Here, he was instrumental in advancing significant fiscal reforms, notably contributing to the introduction of the Goods and Services Tax (GST).

After returning to his cadre for a year-and-a-half as additional chief secretary and commissioner of commercial taxes, Somanathan helped facilitate the state’s transition to the new tax regime.

An important decision to this effect was a circular he issued on 31 May 2019, which provided detailed protocols for roving squad officers tasked with intercepting and inspecting goods vehicles. This was aimed at standardising procedures, reducing ambiguity, and promoting fair practices in the enforcement of GST regulations.

One of the PM’s most trusted officers

Over the years, Somanathan came to enjoy the PM’s trust. In 2019 itself, he returned on central deputation to eventually rise to become the country’s topmost civil servant—a position he has been in for the last eight months.

From 2019 to 2024, Somanathan served in his home turf—the finance ministry—first as the expenditure secretary and then as the finance secretary.

As expenditure secretary, Somanathan played a crucial role in reshaping India’s fiscal policy by prioritising capital expenditure (capex) to drive economic growth, especially in the post-COVID recovery phase.

This was given his own belief that capex creates long-term assets and has a higher multiplier effect on the economy compared to revenue spending. He achieved significant success in this regard, with capital expenditure allocations growing from around rupees 4.39 lakh crore in FY21 to over rupees 10 lakh crore in FY24.

He was also one of the primary architects to design the government’s Product-Linked Incentive Scheme (PLI).

(Edited by Sanya Mathur)