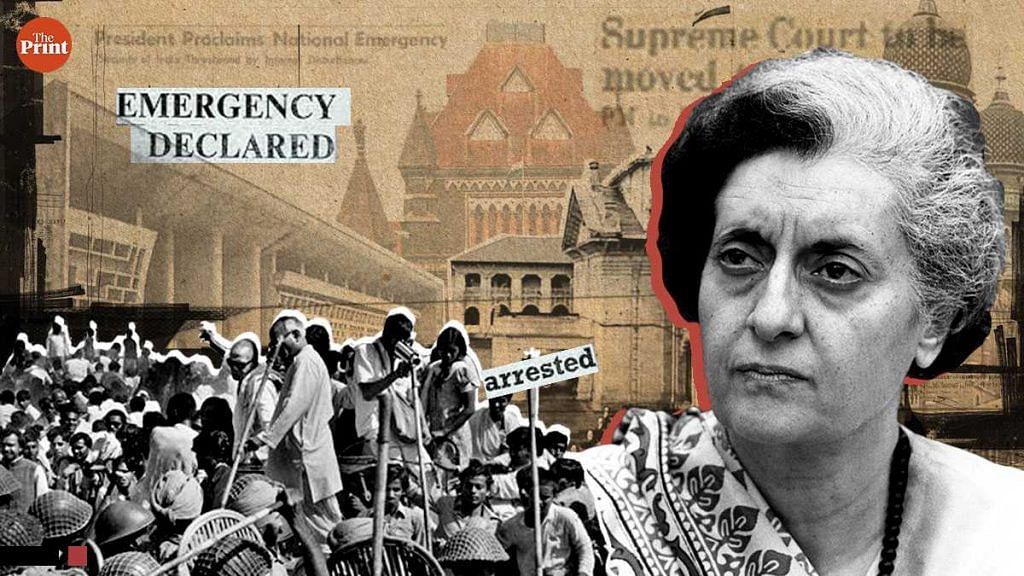

New Delhi: “The President has proclaimed Emergency. There is nothing to panic about.”

The year was 1975 and this declaration by former Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, made over the All India Radio, marked the beginning of the 21-month period in India’s history that is often designated as the country’s “darkest hour”, its “blackest era”.

The announcement was made just hours after then President Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed had signed the order on Indira Gandhi’s advice late at night on 25 June.

As soon as the orders were passed, political rivals, activists and dissenters across the board were jailed. However, personal accounts from the time have since recalled how “the courts seemed to be the sole area that had not succumbed to the fear psychosis prevailing in the rest of the country”.

The trigger to the Emergency was an Allahabad High Court judgment and a Supreme Court order that refused to grant an absolute stay on this judgment.

And the 21-month period from 1975 to 1977 saw strikes from lawyers’ associations, anti-government verdicts from various high courts, transfer of judges, demotions, demolitions, and a supersession so grave that it immortalised the judge and is still used as an example highlight the perils of executive interference in judicial independence.

Commenting on how the judiciary stood defiant during the time, senior advocate Dushyant Dave told ThePrint, “It is not easy for judges to stand up to powerful executive like Mrs Gandhi or Mr Modi. They are always very powerful and every section of society feels a little cowed down by them.

“And the judiciary is no exception, as it might have judges who might not want to cross paths with such powerful political leaders. Of course, we have also seen that the consequences are very serious for crossing path during the Emergency.”

Talking on whether the judiciary is standing up as proactively for civil liberties as it did back then, former Supreme Court judge Justice M.B. Lokur also spoke of the consequences that judges need to face.

“No way! Those who stand get transferred. Look at the allegations made by a sitting judge of the Karnataka High Court. How much worse can it be? Others get punished in a more subtle way,” Justice Lokur told ThePrint,

He was referring to the allegations made by a Karnataka High Court judge who said this month that he was indirectly threatened with a transfer.

Also read: How Emergency made it to school textbooks during Congress raj

The first pushback

On 12 June 1975, Justice Jagmohan Lal Sinha of the Allahabad HC held PM Indira Gandhi guilty of two corrupt practices and declared her election to the Lok Sabha in 1971 “null and void”.

According to senior advocate and former law minister Shanti Bhushan, when Justice Sinha was hearing arguments in the case, the then Chief Justice of the Allahabad HC, Justice D.S. Mathur, visited Justice Sinha with his wife. Justice Mathur was related to Gandhi’s personal physician.

He then reportedly dropped a “subtle hint” to Justice Sinha, saying that his name had been considered for elevation to the Supreme Court and that he would get the appointment as soon as he delivers the judgment in Gandhi’s case.

However, Bhushan says that Justice Sinha “maintained a discreet silence” and delivered the verdict setting aside Gandhi’s election.

Bhushan was representing Raj Narain, who had challenged Gandhi’s election before the high court, and Gandhi’s case was being argued by the legendary Nani Palkhivala.

When Gandhi lost the case, an appeal was quickly filed in the Supreme Court, on the most “astrologically auspicious date”.

The appeal was presented before the vacation judge, Justice Krishna Iyer, who refused to grant an absolute stay on the high court verdict on 24 June 1975. He only granted a conditional stay, meaning Gandhi could not vote or participate in the proceedings as a member of Parliament but could sign the Register of Attendance to save the seat.

The court said she could participate in the proceedings as Prime Minister, but without a vote, and she could continue holding the office of the Prime Minister.

A day later, the Emergency was declared.

One of the first instances of a pushback from the legal community after the declaration of Emergency came from within Gandhi’s circle. Her own lawyer, Palkhivala, refused to appear for Gandhi in her election petition before the Supreme Court anymore.

The then additional solicitor general (ASG) Fali S. Nariman, who had also vetted the grounds for Gandhi’s appeal, quit from his post two days after the Emergency was declared with a one-line resignation letter.

‘Lock up the high courts’

The fire of resistance among the legal community then spread inside the courtrooms as well as outside.

According to journalist Coomi Kapoor’s book, The Emergency: A Personal History, all the bar associations across the country, except the Calcutta Bar Association, issued statements condemning the Emergency.

In October 1975, resolutions were passed during an ‘All India Civil Liberties Conference’, condemning the arbitrary arrests and censorship during the Emergency, demanding the release of detenues and restoration of civil liberties.

This conference was presided over by a former CJI, Justice J.C. Shah and was dominated by lawyers.

Following this, when former judge of the Bombay High Court, Justice N.P. Nathwani, decided to organise a similar conference in Bombay in October 1975 to discuss “civil liberties and the rule of law under the Constitution”, the commissioner of police refused permission.

The state government went a step further and banned any public meeting where the Emergency could be discussed or even referred to.

Nathwani took the matter to the Bombay High court — 157 lawyers, led by Palkhivala, appeared for the petitioners and got the ban overturned. However, the order and the judgment were stayed by the Supreme Court soon after.

During those months, several lawyers, including P.N. Lekhi and M. Rama Jois, were also arrested and jailed. In March 1976, 200 chambers of lawyers practising in Delhi’s Tis Hazari courts were demolished, without notice and 43 lawyers were jailed, according to a paper titled ‘The judiciary and the bar in India during the Emergency’ by noted jurist A.G. Noorani.

The general body of the Supreme Court Bar Association condemned the demolitions in an emergency meeting held on 30 March 1976, and demanded the release of the lawyers and restoration of the chambers.

The threat posed by lawyers and courts of the country — specially the high courts — was also well known in the corridors of power at the time.

Both Siddharth Shankar Ray, then chief minister of West Bengal, and Om Mehta, the powerful Minister of State for Home, had reportedly spoken about Sanjay Gandhi’s plans “to lock up the high courts” and cut off the electricity supply to newspaper offices after the declaration of Emergency. The high courts were spared the electricity black out.

And then came the orders, of high courts ruling against the government and of the government responding by transferring such judges without their consent.

Also read: ‘Will Gandhis apologise for Emergency?’ News Nation asks. Mirror Now on Sasikala political exit

The nine high courts

At the time the Emergency was declared, Article 359 of the Constitution allowed the government to suspend the right to approach courts for enforcement of all fundamental rights during an Emergency.

Accordingly, two days after the Emergency, on 27 June 1975, the President issued another order, suspending the rights of the citizens to approach the courts for enforcement of their fundamental rights under Article 21 (right to life and personal liberty), Article 14 (equality before law) and Article 22 (protection against arrest and detention).

This effectively meant that the order barred citizens from approaching the courts to challenge illegal arrests and detentions.

The main tools of the government at the time were the Defence of India Act, 1971, and the Maintenance of Internal Security Act (MISA), 1971. The laws empowered the government to ban public meetings and impose press censorship. MISA allowed it to detain people without trial through executive orders.

Several detainees at the time turned to the courts with habeas corpus petitions. At least nine high courts — Allahabad, Andhra Pradesh, Bombay, Delhi, Karnataka, Madras, Madhya Pradesh, Punjab and Haryana, and Rajasthan — ruled in favour of citizens and allowed them to file habeas corpus petitions challenging arrests and detentions.

The transfers and demotions

However, several high court judges who passed these orders faced retaliations.

For instance, a Delhi High Court bench comprising Justices S. Rangarajan and R. Aggarwal came to the rescue of The Indian Express journalist Kuldip Nayar on 28 April 1976, quashing his arrest under MISA.

Justice Aggarwal, who was an additional judge then, was not confirmed as a permanent judge in the high court, despite a recommendation by the chief justice of the HC, who called him an “asset to the high court”.

Even though he had worked as an additional judge in the HC for nearly four years, Gandhi refused to accept the recommendation. He had to revert as a sessions judge.

The Shah Commission, which was appointed by the Janata Party government in 1977 to inquire into the illegalities committed during the Emergency, had looked into Justice Aggarwal’s case and called it “a case of misuse of authority and abuse of power”.

The other judge on the bench, Justice Rangarajan, was transferred to the Gauhati High Court.

Another additional judge, Justice U.R. Lalit of the Bombay High Court, who had also ordered the release of a few detainees, was not confirmed as a permanent judge, despite recommendations from the chief justice of the high court, the chief minister of Maharashtra, the CJI and law minister H.R. Gokhale.

This was after Gandhi personally wrote a one-line note saying, “I do not approve of giving him another term”.

Judges who passed orders in similar habeas corpus cases met a similar fate. For instance, justices D.M. Chandrashekar and M. Sadananda Swamy, who had quashed the detention of leaders of various political parties, including BJP leaders A.B. Vajpayee and L.K. Advani, during the Emergency.

Justice Swamy was transferred to the Gauhati High Court and Justice D.M. Chandrashekar, who headed the bench, was transferred to the Allahabad High Court.

According to the then law minister Shanti Bhushan, as many as 21 judges were transferred during the Emergency without their consent.

On 5 April 1977, in the days after the Emergency added, Bhushan gave the Lok Sabha a list of these judges and said that they would be transferred back to their original place after obtaining their consent.

‘SC packed with pliant judges’

However, while the high courts were fearlessly passing verdicts in favour of rights and liberties, a major blow to the Constitution came from the Supreme Court in the historic ADM Jabalpur judgment.

In appeals challenging the high courts’ judgments that allowed habeas corpus petitions, a five-judge bench of the Supreme Court ruled in favour of the government.

The majority verdict held that nobody could ask for any relief from a court as the fundamental right to personal liberty had been suspended — not even if the order of detention was unauthorised or was mala fide or a wrong person was detained.

The case was heard by Chief Justice of India A.N. Ray, and justices H.R. Khanna, M.H. Beg, Y.V. Chandrachud and P.N. Bhagwati — over a period of 37 working days, from December 1975 to February 1976.

Justice Khanna, however, disagreed with the majority verdict — an opinion that cost him chief justiceship. Despite being the most senior Supreme Court judge, he was superseded by Justice Beg as Chief Justice in 1977. Justice Khanna resigned the same day.

Before this judgment, an arrest warrant under MISA was also issued against advocate Ram Jethmalani, who was then the chairman of the Bar Council of India, following his speech at the Palghat Lawyers Conference in Kerala on 25 January 1976. At the conference, he had famously launched a tirade against Indira Gandhi and Sanjay Gandhi.

While about 300 lawyers, led by Palkhivala and Soli Sorabjee managed to get a stay on the arrest warrant, Jethmalani left India a day after the ADM Jabalpur judgment was pronounced on 28 April 1976. He caught a flight to Canada and managed to get political asylum in the US, becoming the first person to be granted asylum because of the Emergency.

Post-Emergency, the legal profession was acknowledged as having “fared the best” during those months. Jayaprakash Narayan also highlighted the difference in approach taken by the Supreme Court and the high courts of the country during the period of the Emergency.

He was quoted as saying, “The high courts have come out with flying colors in the present crisis.”

“But the record of the Supreme Court is unfortunately very disappointing, mainly because Mrs. Gandhi has packed it with pliant and submissive judges except for a few,” he added.

Another former judge of the Delhi High Court, Justice Rajindar Sachar, who was also one of the judges transferred during the Emergency, later asserted that if only the Supreme Court had taken the same view as the nine high courts, “the Emergency would have collapsed immediately”.

Meanwhile, Justice Khanna’s dissent was noticed the world over. An article published in The New York Times on 30 April 1976 said, “If India ever finds its way back to the freedom and democracy that were proud hallmarks of its first eighteen years as an independent nation, someone will surely erect a monument to Justice H.R. Khanna of the Supreme Court.”

‘Drift away from civil liberties’

Comparing the judiciary from the time of the Emergency to the present, Dave told ThePrint, “The judiciary from the Emergency was a mixed bag, as it is today.”

“There were certain lawyers and judges who were very courageous… There weren’t too many but they were there… Today also, I’m sure there are some great, courageous judges. There are judges who are fiercely independent. They see the injustices meted out to certain sections of society, and they stand up for citizens’ fundamental rights.”

However, he added that “the bar has not been as strong as it should be”.

“It is something we need to introspect as lawyers,” he added.

Speaking about the state of the judiciary. Dave referred to the controversies surrounding certain transfers.

“We don’t have an Emergency and these were not executive decisions, the collegium punished them, I’m sure at the suggestion of the executive.

“So, it is a matter of deep regret that the collegium, of the senior most judges of the Supreme Court succumb to the pressure of the executive, for transferring them.”

Justice Lokur also opined that the importance given to civil and personal liberties has “diminished considerably over the last few years”.

This view was echoed by senior advocate K.T.S. Tulsi, who spoke about the judiciary’s emphasis on civil liberties in the past.

“There was a time when when there was a significant amount of emphasis on civil liberties and personal liberties,” he said.

“They have been held to be the heart of the Constitution. And yet there has been a drift over the past 25-30 years, away from safeguarding civil liberties.

“But I do personally think that the Indian judiciary has found a just balance between the rights of individuals and the rights of the society,” he added.

Dave emphasised the need for the judiciary to be “far more vigilant in protecting the rights of citizens”.

“I won’t say that all is lost though, there are still some outstanding judges in our courts, but there are also issues in which several judges have failed the country… It all depends on individuals. I don’t think as an institution, judiciary or the lawyers can be condemned.”

“I do feel that judges need to follow the letter of the law very strictly. They should have zero tolerance towards violators but they should always protect innocent citizens, journalists and members of the minority community by the party in power, and free them,” he added.

(Edited by Zinnia Ray Chaudhuri)

Also read: Plea seeks 1975 Emergency proclamation be held unconstitutional, SC issues notice to Centre