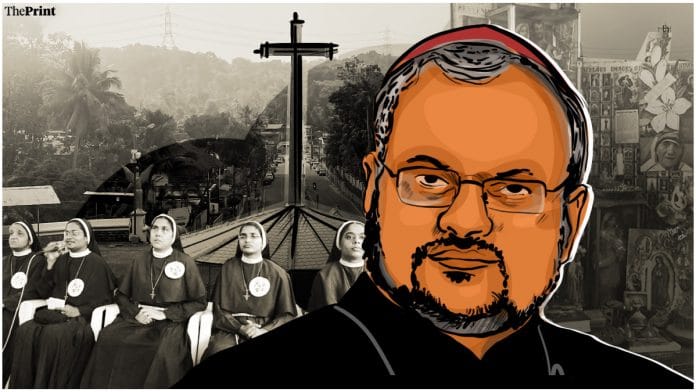

Kochi/Kuravilangad: Ask someone in Kerala’s Kuravilangad where the St. Francis Mission Home is, and they might not know. But mention the infamous former bishop Franco Mulakkal, and they nod for sure. In the four years since he was accused of rape by a nun, Kerala’s church community has split into a for-and-against divide — rife with politics, intrigue, and wild, whispered conspiracies.

And then came the shock judgment last month by a sessions court in Kottayam. The former bishop was pronounced not guilty.

The convent is like a formidable fortress at the end of a dirt road, tucked away in the middle of thick, quiet forest. All visitors are looked at with suspicion. The convent doors open briefly only to let in a man delivering tapioca, then slams shut. Outside, two policemen keep vigil. Information about guests must be relayed directly all the way up to the Mother Superior herself.

St. Francis Mission Home and its former bishop, 57-year-old Franco Mulakkal, are at the centre of a sexual assault case that rocked both the church and the state. In 2018, a nun — then Mother Superior — accused Mulakkal, who was then bishop, of raping her 13 times between 2014 and 2016. Every alleged incident took place in the convent’s guest room number 20.

The sessions court judgment branded the case as one in which “the grain and chaff are inextricably mixed up”. It mentioned in-fighting and rivalry amongst the nuns for “power, position and control over the congregation” and dismissed the complainant’s testimony as “inconsistent”. For the nun’s supporters, the judgment is a travesty of justice, while the bishop and his followers see it as “God’s verdict pronounced on earth”.

Behind the convent’s closed doors, too, people are polarised. There are two distinct groups: those who believe the complainant, and those who do not.

ThePrint tried to contact the nun and her supporters in the convent over the phone, but they said they aren’t ready to talk about the shock judgment just yet. However, they have not given up the fight. The police are likely to file an appeal in the Kerala High Court, and the nuns are prepared to take the legal battle forward.

“Until the truth is revealed, we will fight,” Sister Lissy Vadakkel, who lives in another convent and is the first person the nun confided in, said. “Though this period is difficult for all the nuns, we should all stand together and wait until the truth comes out.”

Also Read: Inconsistent statements, church rivalry — why Kerala court acquitted ex-Bishop Franco Mulakkal

How it all started: Kitchen renovations and an ironed cassock

The story begins with kitchen renovations.

Exactly eight years ago, in February 2014, Bishop Franco Mulakkal arrived at the convent in Kuravilangad to supervise the convent’s kitchen renovations. The bishop and the nuns belong to the Missionaries of Jesus, a Latin Catholic order that is headquartered in Jalandhar, Punjab, with convents in Kerala and Bihar. As the most powerful authority in the mission, Bishop Franco oversaw several administrative functions, including adding a new kitchen to the convent. According to court documents, he later handed over the responsibility for the renovation, estimated to cost Rs 8 lakh, to the convent’s then Mother Superior.

During one visit in May, Mulakkal told her to iron his cassock, which she did, according to court documents. When she brought it up to him, he asked her to fetch papers related to the renovation. Again, she complied and returned with the papers at around 10.45 pm. Mulakkal invited her in and then, according to her complaint, bolted the door and sexually assaulted her for the first time.

When Sr. Lissy, who is the nun’s “spiritual mother,” visited the convent over Christmas in 2014, she mentioned that renovations looked good. To her surprise, the nun told her that there was a sad backstory: she had been assaulted, she had lost her vow of chastity, and now she wanted to die.

Over the next few years, as the alleged assaults continued, the nun told a handful of people. Sisters Anupama, Alphy, Nina Rose, Ancitta, and Josephine, who live with her, formed a close-knit group of support around her.

But believing the nun meant going against the bishop, and therefore the church.

Those who stood by her paid a steep price. Like the complainant and her supporters at the convent, Sr. Lissy has essentially been ostracised by her community. Unlike them, however, she is by herself.

Sr. Lissy belongs to another congregation, and lives in Muvattupuzha. Today, she eats alone, prays alone, and lives alone in a small room that used to be her convent’s parlour, with policewomen in plainclothes stationed outside her door. The convent takes care of her basic needs by giving her a place to sleep and food to eat, but that is all. The sisters don’t interact with her, and pass by without looking at her. She’s not angry about their reaction — but she is hurt.

“How can the sisters turn against their own?” she asked.

She has built a shrine in the corner of her room, where she prays for the nun and the other sisters. She’s also plastered the walls with photos of Jesus Christ and saints. Her only companions these days, she says, are those who live in Heaven.

How the story came out

The battle lines weren’t drawn immediately. There were several attempts to distract the nuns from talking about the assault, which eventually snowballed into character assassination, victim blaming, and wild allegations — all before the FIR was even filed.

In December 2016, after the nun had confided about the alleged assaults to those close to her and to priests during confession, she was accused of having an affair with her first cousin’s husband. In February 2017 she was removed from her post as the congregation’s Kerala-in-charge. She told her superiors that it was revenge for not yielding to the bishop’s demands. In May 2017 she was removed from the post of Mother Superior.

Between November 2017 and June 2018, the bishop filed several cases against the nun and the five sisters supporting her in the convent. He even claimed they had threatened to kill him. The church also tried to isolate the women from each other by transferring them to different convents.

The nun, meanwhile, told a committee constituted by the new Mother Superior in January 2018 that the bishop was retaliating against her for not giving in to his sexual advances and was also targeting the sisters who were supporting her. In May 2018, the sisters couriered letters to Pope Francis, Cardinal Marc, and Cardinal Luis in Rome, but they went unacknowledged. Court documents revealed that as rumours continued to swirl about the nun being a woman of “easy virtue”, she e-mailed the Vatican’s emissary in India, the apostolic nuncio, on 24 and 25 June 2018. A reply never came.

The nun and her supporters were willing to settle the matter within the church, as long as provisions were made for their safety. One of their requests was to be transferred to another Missionaries of Jesus convent in Bihar, and that it should be placed under a different diocese, but it was denied.

Many say that had the nuns’ requests been dealt with effectively, the FIR would never have been filed. But they were not, and an FIR was registered in June 2018.

And then things changed forever.

From arrest to acquittal

When the bishop still hadn’t been arrested by September 2018, a group of sisters and their supporters began a protest near Kochi’s High Court. The unprecedented agitation garnered major media attention and galvanised public support for the complainant and her friends.

But, members of their congregation weren’t as impressed. The Missionaries of Jesus began a probe looking into the protesting nuns, sending a clear message; the nuns’ allowances were also allegedly cut around this time. On 21 September 2018, about 10 days after the protests started, the police finally arrested Mulakkal.

However, suspicion towards the insubordinate sisters continued as the case made its way through the legal system. The trial began at Kottayam’s Additional Sessions Court in September 2020. Meanwhile, within the convent, the complainant and her supporters were increasingly left out of mission work.

“The church protected itself,” advocate Sandhya Raju, who is on the panel of lawyers representing the nuns in the case, said. “The church felt like it needed to protect its reputation at the cost of its own people.”

Raju is also a member of Sisters in Solidarity, a group formed by Catholic feminists in support of the nuns. She helped pave the road to the bishop’s initial arrest in 2018 by filing two public interest litigations calling for it.

There was a sinking moment during the trial when Raju felt the bishop wouldn’t get the full sentence for rape — but she didn’t expect him to go scot-free. What she did expect was tacit support for the bishop from within the church.

The bishop’s defence team maintained throughout that he was being framed, and that the nun wasn’t an ordinary victim. Senior advocate B Raman Pillai, who led the defence, said that it was the bishop’s choice to move beyond the church to the courts.

“The sisters were ready for a compromise, but the bishop was adamant. He believed in the power of the court to clear his name,” Pillai said.

He told ThePrint that the evidence wasn’t just inconsistent, some of it was fabricated too. “It’s not the church vs. the sisters. It was the entire community of sisters and the media against the bishop,” he added.

And now, after the acquittal, it’s almost as if the case has been swept under the rug. One nun, Sr. Saritha, shrugged and smiled when the case was mentioned. She had stepped outside the St. Francis Mission Home on an errand and said that she’d only just been transferred to Kuravilangad from Jalandhar. She’s officially been a nun for less than a month, and is happy in her new life. She had nothing to say about the case.

Also Read: How the case of Kerala Catholic nun Sister Abhaya turned from suicide to murder in 28 yrs

Support for the bishop

The congregation’s reaction to the allegations against the bishop isn’t surprising when members of the church have done their best to discredit the complainant.

Several nuns were transferred to the convent from the Jalandhar diocese. Sr. Anupama had previously said they’d been transferred to Kuravilangad to “torture” the rebellious nuns — the bishop enjoys unequivocal support from his Jalandhar congregation.

He was given a hero’s welcome when he returned to Jalandhar after he was granted bail in 2018. People celebrated his acquittal in January by bursting firecrackers, distributing sweets, and dancing to the dhol (drums). A few of the trial’s defence witnesses were also from the Jalandhar diocese.

“The majority of churchgoing Catholics still do not believe that a rape could have happened,” Dr Kochurani Abraham, a feminist theologian, said. She was one of the founders of Sisters in Solidarity and one of the group’s closest confidants.

“The Indian church is highly clericalist, and clerics are seen as representative of God. When that kind of cleric gets into scandal, it becomes difficult for an ordinary, average, churchgoing Catholic to believe he could be at fault,” she added. “They would like to believe he’s innocent, and whoever’s accusing him is cooking up a story.”

One parish priest in central Kochi, who asked not to be named, acknowledged this dilemma. “If people can’t trust their priest, how can they trust that his word is God’s?” he asked.

Scandal within the church

Plenty of theories and rumours swirl around to explain why the nuns accused the bishop of rape, besides the actual possibility of rape itself.

The same parish priest speculated that the case is an external effort to destabilise the church. He questioned why “purdah people” were present at the 2018 protests calling for the bishop’s arrest. He also suggested that the bishop and the church were involved in countering the drug problem in Punjab and that perhaps there was a larger conspiracy to make him stop.

“They wanted to fix the bishop — maybe at the insistence of some individual actors,” Raman Pillai, the bishop’s defence lawyer, said. He pointed to the bishop’s relatively young age and quick ascent through the clergy as a possible reason for the internal politics.

There are also accusations that the nun was in a consensual relationship with the bishop.

An official at a Syro-Malabar church in Kuravilangad told ThePrint that in his eyes, the case is a personal, “earthly” issue and both parties are culpable — but after the judgment, there’s no need for any further discussion.

“The Catholic church is a vast ocean,” he said. “This is just the bursting of a bubble. It will not affect the vastness of the ocean.”

But several such bubbles have burst before: Kerala is no stranger to sex scandals within the church.

In another case in 2018, four priests of the Malankara Orthodox Christian Syrian Church were booked for allegedly sexually assaulting and blackmailing a married woman.

One priest, Father Robin Vadakkumchery, was accused of raping and impregnating a 16-year-old minor. According to reports, he pressured the girl’s father to claim paternity in the case until a DNA test proved otherwise. Vadakkumchery was convicted in 2019 — in 2020, the survivor approached the Supreme Court asking for permission to marry the priest

In 1992, a 19-year-old studying to be a nun was found dead in a well. The Abhaya case, as it came to be known, made national headlines as it unfolded. She was murdered by two priests and a nun, whom she witnessed in a compromising position. One priest and the nun were convicted of murder 28 years later, in 2020.

Also Read: Kerala priest Vadakkumchery defrocked — the 2016 rape case against him and its many twists

Reforming from within

The church might have passed the buck to the courts in the case of Bishop Franco, but there are detractors who think the church should play a firmer role in addressing the issue.

One such person is Father Paul Thelakat, a former spokesperson of the Syro-Malabar Synod and an editor of the Christian publication Sathyadeepam. He said that the case has seriously undermined the credibility of the bishops and the leadership — first because the leadership failed in addressing the nuns’ complaint, and second because the church machinery failed to solve it within the sphere of the church.

“It is a sad reality that although the Catholic Church has a very good legal system, there is no law, I mean canon law, to deal with an offence done by a bishop,” Thelakat said.

Following the verdict, there are “very many serious issues” for the church to address, he added. “Is the acquitted [Mulakkal] going back to his position as the bishop of Jalandhar? The acquittal is not honourable, it is due to lack of evidence. Can he go back? Does the court order make him innocent?” Thelakat asked. “These are questions the church leadership cannot escape.”

A section of Catholics believe that the church has resisted real progress. “Within this rigid, orthodox, Syro-Malabar community, you have a lot of affluence and activity — special prayers, building churches and church festivals,” Anita Cheria, director of OpenSpace and a member of Sisters in Solidarity, said. “But there’s no progress when it comes to gender justice in the church.”

There are already several bodies working towards addressing gender justice and reform within the church, like the Kerala Catholic Church Reformation Movement. Other groups like the Indian Women’s Theologian Forum and Sisters in Solidarity are also challenging the silence and inaction of Catholic church authorities on sexual abuse by the clergy.

On 6 February 2022, Sisters in Solidarity sent a detailed letter to church authorities at the Vatican and in India. The letter, a copy of which is with ThePrint, demands care for the sisters, and to not give Mulakkal any administrative responsibilities until the case is completed. It also demands that an internal complaints committee be set up at every church institution. The statement is endorsed by nearly 1,300 Catholics from all over the world.

“We have to address things within the church, as well as outside,” Dr Abraham, who helped prepare the statement, said. “The fact that there are many thinking along with us itself is hope-giving.”

Also Read: How Kerala church’s ‘love jihad, narcotics jihad’ taunts are hurting Muslim businesses & society

Picking up the pieces

The fight has exhausted the nuns. They were ready for a long legal battle, but the bishop’s acquittal at the sessions court has made it an uphill journey. Today, they’re processing the judgment, and aren’t ready to break their silence yet.

“Those two words – ‘not guilty’ – were like a breaking point,” Cheria said. “And it didn’t stop at not guilty. The judgment almost puts all the accusation on the victim itself.”

The judgment also notes that the sisters “were not participating in the day-to-day activities of the convent,” and that this pointed towards “indiscipline, non-cooperation and lack of mutual respect among the members of the congregation”. But the sisters and their supporters say they’ve been deliberately left out of mission work.

Over the last three years, the group has had to find different ways to keep themselves occupied. Sr. Anupama, Sr. Neena, and Sr. Ancitta are pursuing master’s degrees in social work through the Indira Gandhi National Open University. They had completed the fieldwork right before the trial was heard. Sr. Alphy has done a master’s in library science.

“They’ve been doing many different things together — the idea is to find positive ways of staying engaged. One can’t think about the case 24/7. It’s also a need as they’ve not been given any mission work,” said Cheria. “Alphy is passionate about growing vegetables and plants, and Anupama is now an expert on poultry.”

Support has been pouring in from outside the convent gates. After the judgment, the nuns received hundreds of letters of support as part of a campaign called Avalkoppam, which translates to “with her.”

Be part of a small campaign where we write letters of solidarity to the nuns. Write your letters to solidarity2sisters@gmail.com

Mine below ?? #avalkoppam #withthenuns pic.twitter.com/74ExLVMool

— Nisha Susan (@chasingiamb) January 19, 2022

The nuns have also received support from unexpected quarters: the president of the women’s section of the Conference of Religious India, Sister Maria Nirmalini, wrote to the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of India, urging them to support the nun. Cheria also told ThePrint that the sisters’ immediate families have stood by them in a rare show of solidarity.

“The silver lining in this case is the support of their families,” she said. That’s been a revelation for me, that this also happens in Kerala.”

Cheria, Raju, Dr Abraham, and other members of Sisters in Solidarity have resolved to keep advocating for the nuns. At this moment, the nuns need care, Dr Abraham said. And despite it all, they haven’t lost their faith.

“There’s always a resurrection after death,” she said. “This gives us a reason to fight for justice.”