New Delhi: A decade after it was set up with an aim to foster a dynamic environment for diverse intellectual exploration, Ashoka University appears to be witnessing a shift in academic trends. More students are opting for disciplines with clearer job prospects, moving away from broader academic experimentation that once defined Ashoka’s ethos.

The university, which originally stood out for its strong focus on traditional humanities, attracting renowned scholars like Pratap Bhanu Mehta and Arvind Subramanian, maintains that it does not see these trends as a shift—towards a more “mainstream” approach. But this apparent shift is also reflected in changes to faculty composition, nature of discussions in the classroom and, to an extent, students’ choice of disciplines.

Data shows a trend setting in of more students opting for majors that offer relatively secure career prospects, such as Economics, Finance, and Psychology. At the same time, many are choosing minors in fields like Entrepreneurship and Computer Science to further enhance their skill sets and strengthen their professional profiles.

Ashoka began in 2014 with just 127 students and has since grown to approximately 2,800. It now offers more than 200 subject combinations in a major-minor format, including 12 pure major disciplines and nine minors.

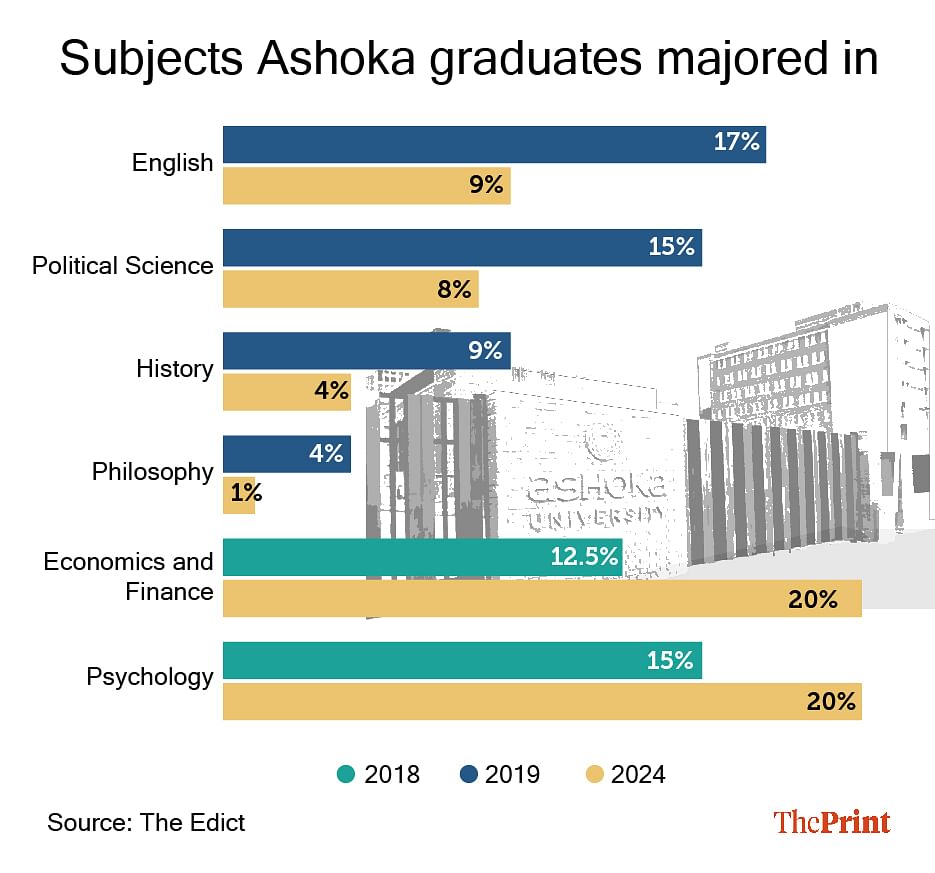

According to data analysed by Ashoka University’s student-led newspaper The Edict, sourced from an internal portal, there has been a noticeable decline in the percentage of students graduating with majors in traditional humanities disciplines.

For example, in 2019, approximately 17 percent of graduates majored in English, but by 2024, this figure had fallen to around 9 percent.

Similarly, the share of students graduating with Political Science as their major dropped from 15 percent in 2021 to under 8 percent in 2024.

History majors saw a similar decline, from 9 percent in 2018 to just 4 percent in 2024.

Philosophy, which previously made up about 5 percent of graduates, now constitutes only 1 percent of the class of 2024, according to The Edict.

Economics continues to be on the rise. This coincides with a dramatic rise in the percentage of students majoring in Economics and Finance or ECO-FIN and Psychology. For instance, in 2018, 12.5 percent of the graduating class had ECO-FIN as their major. This number rose to 20 percent in 2024. Similarly, the percentage of students graduating with Psychology as a major from 15 percent in 2018 to 20 percent in 2024.

Saikat Majumdar, Head of the English department, acknowledged the declining percentage of students pursuing social sciences courses, including English, as majors in recent years. He pointed to several factors contributing to this shift, key among them being the restructuring of undergraduate majors under the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020.

“With the new system, the number of required courses for a major has increased, making it increasingly difficult, if not impossible, for students to pursue double majors,” he told ThePrint over the phone. Majumdar also emphasised the concept of ‘parent’ and ‘passion’ majors in academia. The ‘parent’ major is often chosen for practical reasons, such as job prospects, while the ‘passion’ major reflects a student’s personal interests.

English, for instance, is considered a passion subject.

“In the past, students might have opted for a combination of subjects like Economics and English, but the restructuring of the curriculum has forced many to drop their passion subjects in favor of more traditional, career-focused majors,” said Majumdar.

ThePrint reached Ashoka University for details about the composition of the outgoing batch but was told that the institution “won’t be able to share the exact numbers at the moment”.

Also Read: Nine-year-old Ashoka University is asking the most important question. Who am I?

Move towards more career-oriented disciplines

Several current students from Ashoka University who spoke to ThePrint explained that their subject choices are increasingly focused on fields with stronger employment prospects. In contrast, alumni said they took a more experimental approach to selecting their courses.

For instance, a fourth-year Economics and Finance student said, “When I first joined Ashoka, I intended to pursue an undergraduate degree with a Political Science, Philosophy, and Economics (PPE) major. However, I soon realized that to apply for many postgraduate courses abroad, particularly for a master’s in Economics, you need to be a full Economics major. That was a major factor in my decision to switch out of the PPE track.”

The student eventually opted for Economics as her major and Psychology as her minor. But as placement season approached, her seniors suggested that having knowledge of Finance would significantly enhance her job prospects.

“Coming from a Humanities background, I had no formal knowledge of Finance, but after hearing that advice, I decided to switch to Economics and Finance. I figured that having a dual focus in these fields would open up better job opportunities for me in the future.”

Her experience is reflected in social media pages of Ashoka University’s Career Development Office. Testimonials on the CDO’s Instagram page show that a majority of students who secured good placements have either a major in Economics or a combination of Economics and Finance.

Another fourth-year student, who opted for Economics as her major, explained to ThePrint, “The idea at Ashoka is to give students the freedom to explore different combinations of subjects and co-curricular activities during their degree. When I mentioned in my interviews that I wanted to study Economics for sure, they emphasized that Ashoka encourages exploration, curiosity, and creating your own curriculum. I did try a variety of courses, including Political Science, until my second year.”

By the time she reached third year, she realised that ultimately she would need a job. “Learning for the sake of learning became a luxury, and I understood it might not lead to tangible results. So, in my third year, I stopped exploring and focused solely on Economics-related subjects.”

The student mentioned that many companies don’t associate roles with Political Science and Psychology majors. “As a result, securing internships can be challenging, especially for non-economics majors. Without the right connections, it’s often difficult to even land an internship opportunity.”

Fahad Hasin, an alumnus of Ashoka University who graduated in 2021, said when he first joined the university, the majority of his batchmates came from metropolitan cities and affluent backgrounds. “It was the kind of crowd that wasn’t overly concerned with survival, which created a culture of experimentation and exploration,” Hasin told ThePrint.

“Students had the freedom and privilege to focus more on intellectual curiosity and personal growth rather than immediate career pressures.”

Hasin, who enrolled in 2017, highlighted that the university’s ethos at the time was centered around interdisciplinary education—encouraging students to explore new areas, find commonalities across fields, and engage in uncharted academic territories. “The idea was to experiment, try things people hadn’t explored before. This was a message consistently propagated by the university through orientations and various communications.”

However, he observed a shift over time. “Now, when you look at the university’s messaging on platforms like social media, there’s an increased emphasis on placements and job opportunities. I understand that this is an important aspect, especially as more students from diverse backgrounds are joining the institution, with increasing concerns about employability.”

In an email response to questions from ThePrint, a spokesperson said Ashoka University does not see this as a ‘shift’.

“Students have always prioritised employment. Ashoka has proved that majors do not correlate to employment fields. We have political science majors going into consulting and history majors going into banking,” read the statement.

Adding, “Economics has always been Ashoka’s largest major, followed by Computer Science and Psychology … The growing interest in Economics and Entrepreneurship reflects current trends in India and around the world and therefore the university is addressing the need.”

The spokesperson also said that significant investments are being made in both sciences and humanities, with efforts to enhance research infrastructure to meet global standards.

Echoing the same, Ashwini Deshpande, head of the Economics department at Ashoka, said share of students opting for Economics has been roughly constant at under 40 percent for the past three years, including Economics Major, Economics Minor, Economics, Economics interdisciplinary (with finance, history and public policy), and PPE (politics, philosophy and economics). “In other words, all students are opting for some Economics courses,” she said in an email response to questions from ThePrint.

Similarly, Supriya Ray, head of the Psychology department at Ashoka University, said the percentage of incoming students opting for Psychology courses has remained fairly consistent between 2014 and 2022, ranging from 11.29 percent to 18.09 percent. Danny Weltman, head of the University’s Philosophy department, also reinforced that the number of Philosophy majors at Ashoka has not changed significantly over the years.

Pursuit of stability & ‘mainstreaming’

But many students and teachers believe that post pandemic, there has been a shift in students’ preferences, hinting that “mainstreaming” of the University also played a role in influencing students’ choices. A fourth-year student majoring in Political Science and English, said students now seek greater stability in their lives and careers, which has led them to prioritize courses that promise a solid return on investment.

This trend persists even though Ashoka offers robust financial assistance.

“Covid has had a significant impact. First, people have become highly job-oriented, seeking structural stability in their lives. Second, it has imposed considerable financial strain. The students coming in now were quite young when the pandemic hit, and they’ve witnessed its effects firsthand. As a result, after three or four years, we’re beginning to see how the pandemic has influenced students’ career choices,” she told ThePrint.

“They’re increasingly inclined to pursue majors that offer solid financial returns. Ashoka, for instance, is an expensive institution, and when you’re paying around Rs 40 lakh for an undergraduate degree, you expect to land a job with a salary package of at least Rs 15-17 lakh,” she said.

She also cited a significant change that has been noted in departments like Political Science, where students once benefited from access to distinguished professors with strong industry connections. “These professors’ recommendations could open doors to prestigious opportunities,” she explained.

But with changes in the faculty, this dynamic changed. “The faculty in Political Science has changed, and with it, the sense of security and mentorship that once existed,” she added.

According to the Ashoka University website, currently, the Political Science department has no faculty members at the professor level. Of the nine full-time permanent faculty members in this department, seven are assistant professors.

Earlier, Pratap Bhanu Mehta, a renowned academic and political scientist, who had previously served as the Vice-Chancellor of Ashoka University, was the face of the department. But he resigned in 2021, stating in his resignation letter that the founders made it “abundantly clear” his association with Ashoka was a “political liability”.

This was followed by the resignation of economist Arvind Subramanian. Later a joint statement was issued by the university board, along with Mehta and Subramanian, acknowledging “some lapses in institutional processes” and pledging to rectify them.

Aditya Roy, a fourth-year student majoring in Economics and Media Studies, explained that this shift has made students more cautious about changing departments. “In the past, many students who started in Economics often switched to other majors, like Political Science. I can say anecdotally that they wanted to learn from well-known faculty members. But that doesn’t seem to be happening anymore,” he said.

“Now, students are much more careful, weighing the stability and reputation of different departments before making any decisions.”

Another fourth-year student, who requested anonymity, said Ashoka University is seeing a shift towards a more diverse academic staff. “The university used to have a reputation for recruiting Ivy League PhDs, but now we also have professors who earned their doctorates from JNU and other prominent Indian universities. There is a growing number of younger faculty members who pursued their academic careers domestically,” he said.

Meanwhile, faculty members cited “mainstreaming” of the institution as another reason behind the shift.

Projit Bihari Mukharji, head of the History department, highlighted the expansion of academic departments, faculty research interests, and increase in student enrollment. “The diversity of academic options available to students has broadened, and the range of their backgrounds and intellectual pursuits has also expanded,” he told ThePrint.

Mukharji also pointed out a shift in the student demographic, noting that more students are coming from salaried families, where future employability is a key concern.

Majumdar, head of the English department, too reflected on Ashoka’s evolving identity.

“When the university was first established, it was relatively unknown and attracted a small group of adventurous, well-privileged students who were willing to take risks on an unconventional education. However, over the years, Ashoka has grown into a well-known brand, attracting a wider range of students from diverse backgrounds. Today, many of those who choose Ashoka do so not just for its innovative approach to learning, but also for the promise of a more conventional, globally competitive education,” he said.

Why does Ashoka still stand out

A student pursuing Economics major who originally had Delhi University as her top choice is a case in point. She ultimately chose Ashoka due to delays caused by the pandemic and high cut-offs. “I couldn’t get Political Science at any of the top colleges because of the high cut-offs, so I decided to join Ashoka instead. But I don’t regret it at all.”

Despite her initial decision, she soon found herself comparing her experience at Ashoka with that of a friend who chose DU for the same course.

She noted the differences in curriculum and assessment methods thus: “Unlike DU, we don’t have a traditional exam system, which gives us more freedom to engage with different interpretations. Our assessments are mostly essay-based, where we take a theoretical concept from the syllabus and apply it to real-world situations. If you only study for exams, you miss the deeper nuances of the subject. Studying beyond exams helps develop a more nuanced and thoughtful understanding.”

One of the defining features of Ashoka University, according to students, is its strong emphasis on research.

“It is one of the only universities in India with a bustling research culture. Most universities introduce research at the postgraduate level, but here it starts at the undergraduate level, and even students are engaging in research,” said another fourth-year student pursuing Psychology as her major, highlighting the institution’s commitment to academic rigor.

At the same time, some students have observed noticeable shifts in the academic environment at Ashoka University in recent years, particularly in the wake of the pandemic.

A fourth-year student pursuing a major in Political Science and English shared pointed to how the crisis impacted students’ habits and academic engagement. “The pandemic had a significant effect on our reading habits. It became harder to stay focused, and many of us struggled to maintain the same level of academic discipline we had before,” she said.

Over the course of her four years at Ashoka, she noted broader changes in the academic culture. “While the faculty has remained relatively the same, I’ve seen a shift in both the student body and the nature of our discussions,” she explained. “Earlier, there was a strong emphasis on exploring different perspectives, challenging ideas, and engaging in theoretical debates. But now, the approach seems more empirical.”

She elaborated on how this change has affected the way students engage with political science: “The discussions have become more data-driven, focusing heavily on evidence and concrete facts, rather than the interpretive or theoretical discussions we used to have.”

Karnav Popat, a fourth-year computer science major who analyzed the graduation trend data for The Edict, explained that things have changed significantly since the pandemic.

“When my batch joined the campus in 2021, we didn’t get to interact much with seniors. By the time we came back in 2022, protests following Pratap Bhanu Mehta’s exit had already concluded, and the senior-most batch had only two months left before graduation,” Popat said. “The gap created by the pandemic meant students didn’t have the opportunity to learn from the existing culture, and what we saw later became the default setting.”

(Edited by Amrtansh Arora)

Also Read: Girish Karnad to Sai Paranjpye, why Indian icons have donated to Ashoka University’s archive

Ashoka University is an example of an experiment gone horribly wrong.

An institution hijacked by the Left to produce ideologically indoctrinated graduates – an institution by the rich, of the rich and for the rich.

One cannot fathom why someone would be willing to pay 40 lakhs for an undergraduate degree in English? Unless of course it’s black money.

One can only hope that better sense prevails and the University shifts it’s focus to core science subjects.

What is inexplicable though is the obsession of The Print with Ashoka University. Every few days there is an article on the University. Is it some kind of paid advertising?

Ashoka is a cesspool. Though the founders are trying hard to weed out the parasites from the system and focus on their core mission.

The fact remains that the founders of Ashoka were duped by the Left-liberal cabal. They initially wanted to create an MIT-like institution which would conduct path-breaking research in the basic sciences and win Nobel prizes for the nation. To this end the founders (all uber wealthy entrepreneurs, industrialists and businessmen) gathered sufficient resources – both monetary and otherwise.

Very unfortunately, word got around of their plans for creating an MIT-like institution in India. The Left-liberal cabal immediately understood that if the sciences and technology were to be the core focus areas for the university (in it’s pursuit of Nobel Prize winning research), there would hardly be any space for members of the cabal.

Now everyone, even the most hardcore socialists and communists, want a high paying job which involves regular trips to the US and other Western nations for “professional” reasons. Utilising their vast network, the Leftist cabal was successful in getting an audience with the founders and tried their level best in impressing upon the founders that what India needed at the moment was a liberal arts university. Initially, the founders were opposed to the idea but it was the UPA era and the Left-liberal cabal had access to every single office in the nation. They left no stone unturned in their quest to get the founders to commit to a liberal arts university. It is anybody’s guess who benefits the most from the arts and humanities faculties.

Unfortunately, the founders eventually agreed to go ahead with the liberal arts idea. The result is that the university (Ashoka) which was intended to focus on Mathematics, Physics and Chemistry research is now focusing on English literature and History.

The professors are all dyed-in-the-wool Leftists. People like Christophe Jaffrelot call the shots at Ashoka. And their ideological antipathy towards Hinduism often results in very uncouth incidents which bring disrepute to the university.

The Left-liberal cabal succeeded in fooling the founders of Ashoka University. That’s the unfortunate reality.