New Delhi: With the aim to modernise India’s education system—all the way from pre-school to PhD—while keeping it “rooted in Indian ethos”, the National Education Policy (NEP) was released on 29 July, 2020 in the middle of the Covid pandemic. Framed by a high-powered committee led by former ISRO chief K. Kasturirangan, it was the third education policy of the country after 1968 and 1986.

NEP 2020 prescribed focus on foundational literacy and numeracy, multidisciplinary education, experiential learning, digital pedagogies, improved access, increasing the gross enrolment ratio in higher education, and promoting research and vocational training. It also prioritised education in the mother tongue, promotion of India’s traditional knowledge, and internationalisation of the education system, among other objectives.

However, five years on, with many of the schemes and programmes recommended under the policy now running, the implementation remains uneven—varying widely across states, regions, and even individual institutions. In many parts of the country, it is fragmented and inconsistent.

One of the major policy recommendations—setting up an overarching body intended to serve as a single-window regulator for higher education, called the Higher Education Commission of India (HECI)—is yet to be implemented, with even the bill yet to be finalised by the government.

And while the system is making steady progress towards the predicted outcomes under NEP 2020, various stakeholders that ThePrint spoke to believe it is still too early to expect widespread results in a diverse country like India, where education is a concurrent subject.

“In a country like ours, where we’re accustomed to over-structured systems, the idea of academic freedom and exploration can feel unfamiliar, even unsettling. That’s why many fear it may fail, or struggle to see how it can be implemented with the same level of rigour,” educationist and policy strategist Meeta Sengupta told ThePrint.

Also Read: Next chapter, India’s military might. NCERT preparing module on Op Sindoor for classes 3-12

The row over three-language formula

NEP’s implementation has been mired in controversy from the beginning. Soon after the policy came into force, Opposition-ruled states objected to the three-language formula—mandating that students learn three Indian languages up to Class 8, and preferably till Class 10.

Southern states, particularly Tamil Nadu, have objected, arguing that it promotes “Hindi imposition”—even though NEP 2020 does not mandate or prefer any specific language under the formula.

Tamil Nadu Chief Minister M.K. Stalin and Union Education Minister Dharmendra Pradhan have had several exchanges over the issue, including spats on social media and in official letters this year itself. In a letter in February, Pradhan had urged Stalin to “rise above political differences”, adding that it is inappropriate for the state to view the policy with a “myopic vision”.

In June, the Mahayuti-led Maharashtra government withdrew its decision of introducing Hindi as the third language, following strong uproar by the Opposition. The state has otherwise adopted NEP 2020.

However, the 2020 policy is not the first one to recommend the three-language formula. It has been in practice since the 1968 education policy.

Currently, all states and Union Territories—except Tamil Nadu, Kerala and West Bengal—have begun adopting NEP 2020 in a phased manner. In May, the Supreme Court had dismissed a plea seeking directions to these three states to implement it, saying that it cannot compel states to adopt a particular government policy.

NEP 2020 focuses on using mother tongue or local languages as medium of instruction for children up to Class 5, and preferably up to Class 8, citing studies that have shown that children learn and grasp non-trivial concepts more quickly in their home language.

Over the last five years, the National Council of Educational Research and Training (NCERT) has released textbooks in 22 scheduled Indian languages. The Central Board of Secondary Education (CBSE) has also asked schools to conduct language mapping of the students, and start offering education in regional languages.

This is not limited to schools. The government has also introduced technical and medical courses in local languages over the past few years. However, there have been concerns over job prospects of students pursuing professional courses in regional languages.

PM-SHRI scheme: Bone of contention

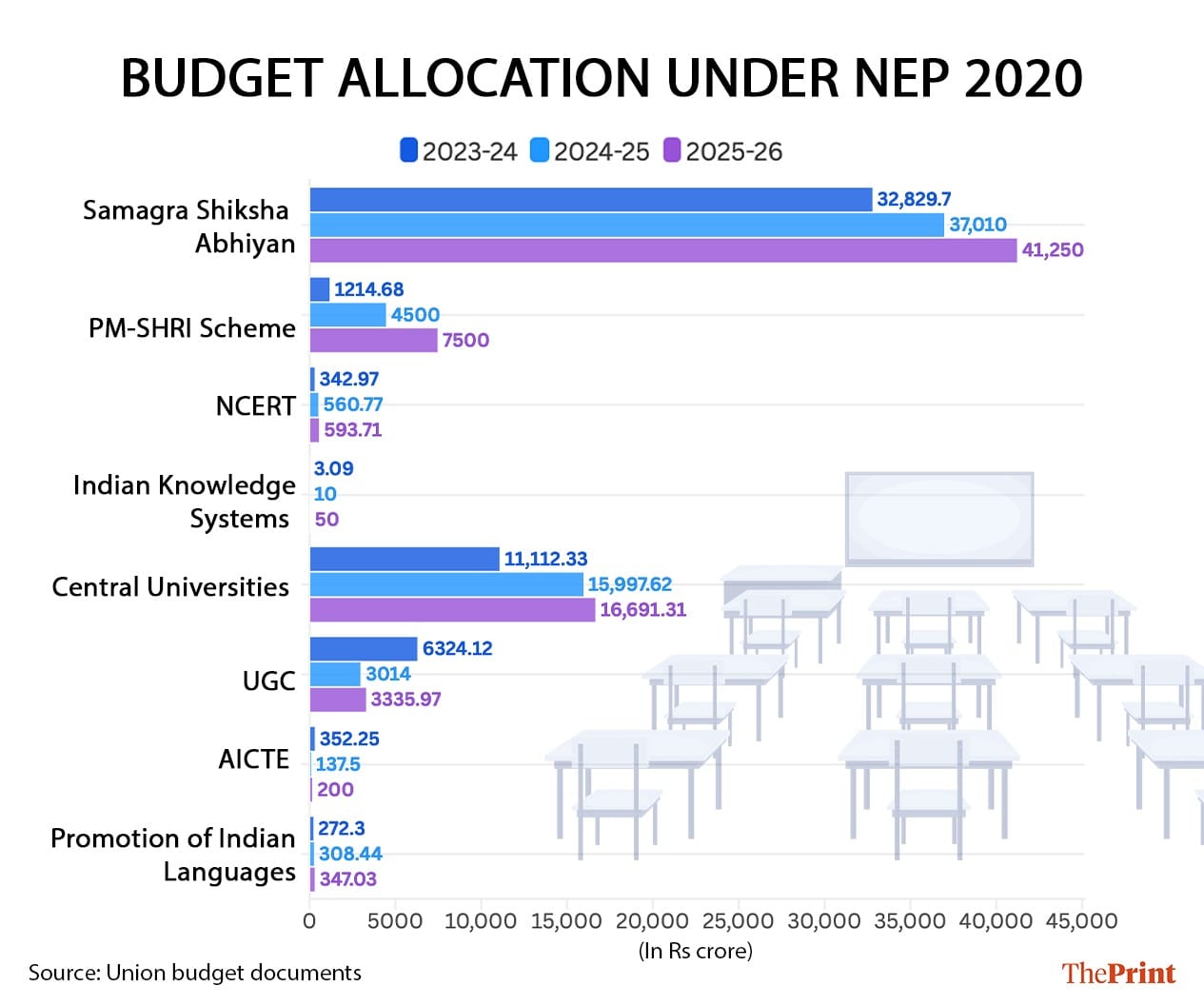

Tamil Nadu, West Bengal and Kerala’s standoff with the Centre worsened after the government announced the PM Schools for Rising India (PM-SHRI) scheme in September 2022, which aimed to upgrade existing schools into model institutions that reflect the vision of NEP 2020, with financial support provided by Centre.

However, a key prerequisite for participation was signing a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with the central government to adopt NEP, which the three states opposed, deeming it as “imposition”.

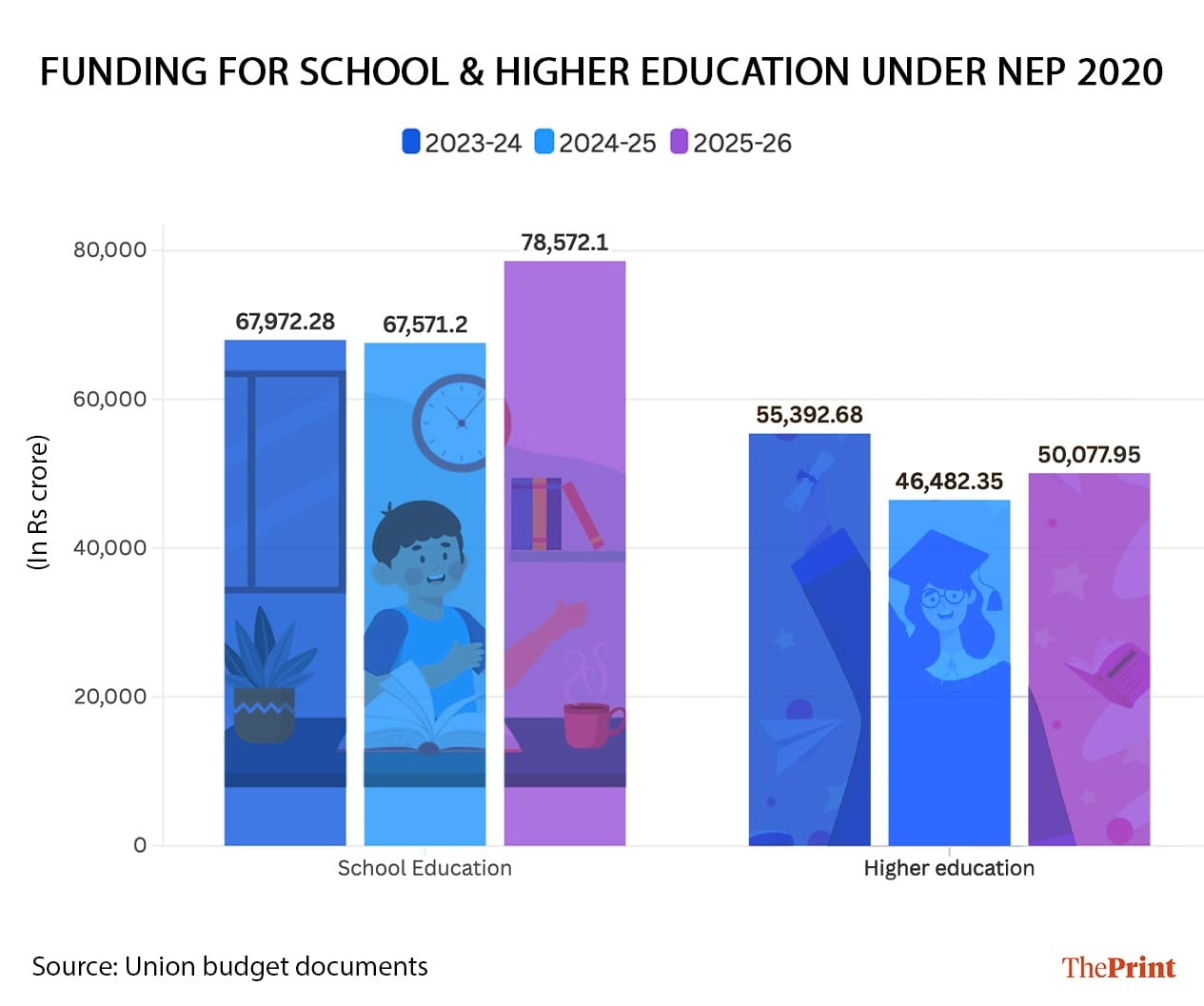

These three states have not yet signed an MoU to adopt the scheme, and as a result, the Centre has withheld their funds for the government’s flagship universal education programme, Samagra Shiksha Abhiyan (SSA), under which PM-SHRI is included.

In a response to a Parliament question on 21 July, the Union education ministry informed that no funds were released to these three states under SSA in the 2024-25 academic year.

Some other states, including Delhi and Punjab, had also resisted initially, but they eventually signed the MoUs after their SSA funds were withheld.

‘Decolonisation’ of education

The National Curriculum Framework (NCF), which serves as the guiding document for school education and textbook development, was released for the foundational stage in 2022, and for the rest of school education in 2023. NCF emphasises incorporating Indian context into education to foster pride in the country’s culture.

Releasing the guidelines in 2022, Education Minister Pradhan had said that NCF’s mandates aim to “decolonise India’s education system”.

Between last year and this year, NCERT has released new textbooks up to Class 8. The common features of these books include greater emphasis on Indian contributions to Science and Mathematics, references to Harappan civilisation as the Sindhu-Sarasvati civilisation, use of “Bharat” instead of “India” in most instances, and reduced focus on the Mughals and Delhi Sultanate.

For example, the new Class 7 Social Science textbook released this April omits references to Mughals and Delhi Sultanate entirely, and instead introduces chapters on ancient Indian dynasties, like the Magadha kingdom, Mauryas, Shungas, and Sātavāhanas.

The new Class 8 Social Science textbook released in July reintroduces the Mughals, but presents them differently compared to older textbooks—highlighting instances of “brutality” and “religious intolerance” during their rule. Meanwhile, the Marathas are portrayed in a more glorified light. While experts have described the changes as an “ideological move” that selectively glorifies or vilifies historical figures, NCERT has defended them as an objective portrayal of history.

The new textbooks also include references to India’s ancient knowledge systems, make greater use of Sanskrit vocabulary, and feature stories of war heroes.

Similarly, in higher education, NEP has introduced Indian Knowledge Systems (IKS), adding indigenous content to the curriculum, with new courses on Yoga, Vedic Mathematics, Astronomy, and other aspects of ancient Indian knowledge.

School education structure overhaul

NEP 2020 replaced the existing 10+2 school education structure with a new 5+3+3+4 framework, covering children from ages 3 to 18 in four stages—Foundational (three years of Anganwadi/pre-school plus Grades 1–2, for ages 3–8), Preparatory (Grades 3–5, ages 8–11), Middle Stage (Grades 6–8, ages 11–14), and Secondary (Grades 9–12, divided into two phases: Grades 9–10 and 11–12, for ages 14–18).

The policy emphasises on early childhood care and education (ECCE), giving “highest priority” to achieving universal foundational literacy and numeracy (FLN) by the end of Class 3. “The rest of this policy will become relevant for our students only if this most basic learning requirement—reading, writing, and arithmetic at the foundational level—is first achieved,” it states.

On 5 July, 2021, then Union Education Minister Ramesh Pokhriyal had launched the National Initiative for Proficiency in Reading with Understanding and Numeracy (NIPUN Bharat), with the aim to ensure that every child in India attains FLN by 2026–27 via interventions like intensive teacher training, innovative pedagogies, play-based and experiential learning, and structured assessments.

Under the same initiative, the ministry also launched “Jadui Pitara”, a collection of learning teaching material (LTM) for the 3-6 years age group, in February 2023. NIPUN Bharat is a part of Samagra Shiksha Abhiyan.

According to teachers and principals at various schools, this was the first time a targeted approach was taken towards improving the financial literacy and numeracy skills of younger children.

Vineeta Nanda, an English teacher at Delhi’s Mount Abu Public School, told ThePrint that she has explored various innovative teaching methods in her 17-year career, but the transformation she has seen in the past five years is unprecedented.

“Under NEP 2020, we’ve shifted from traditional textbook-based instruction to play-based and story-based learning—even in subjects like English. For instance, when teaching grammar, I take students outside to the garden. I point to objects and ask them to identify nouns and pronouns. It makes learning more interactive, relatable, and fun,” she said.

However, the implementation of NIPUN Bharat initiative and focus on FLN differs in private and government schools, with the latter finding it difficult to implement the recommendations due to limited resources, shortage of teachers and poor infrastructure.

Vipin Prakash, president of Rajasthan Primary School Association, said that little has changed so far in government schools. “We’ve been told that textbooks will be revised under NEP 2020 up to Class 5, but we haven’t received them yet. We also haven’t received any training on NEP.”

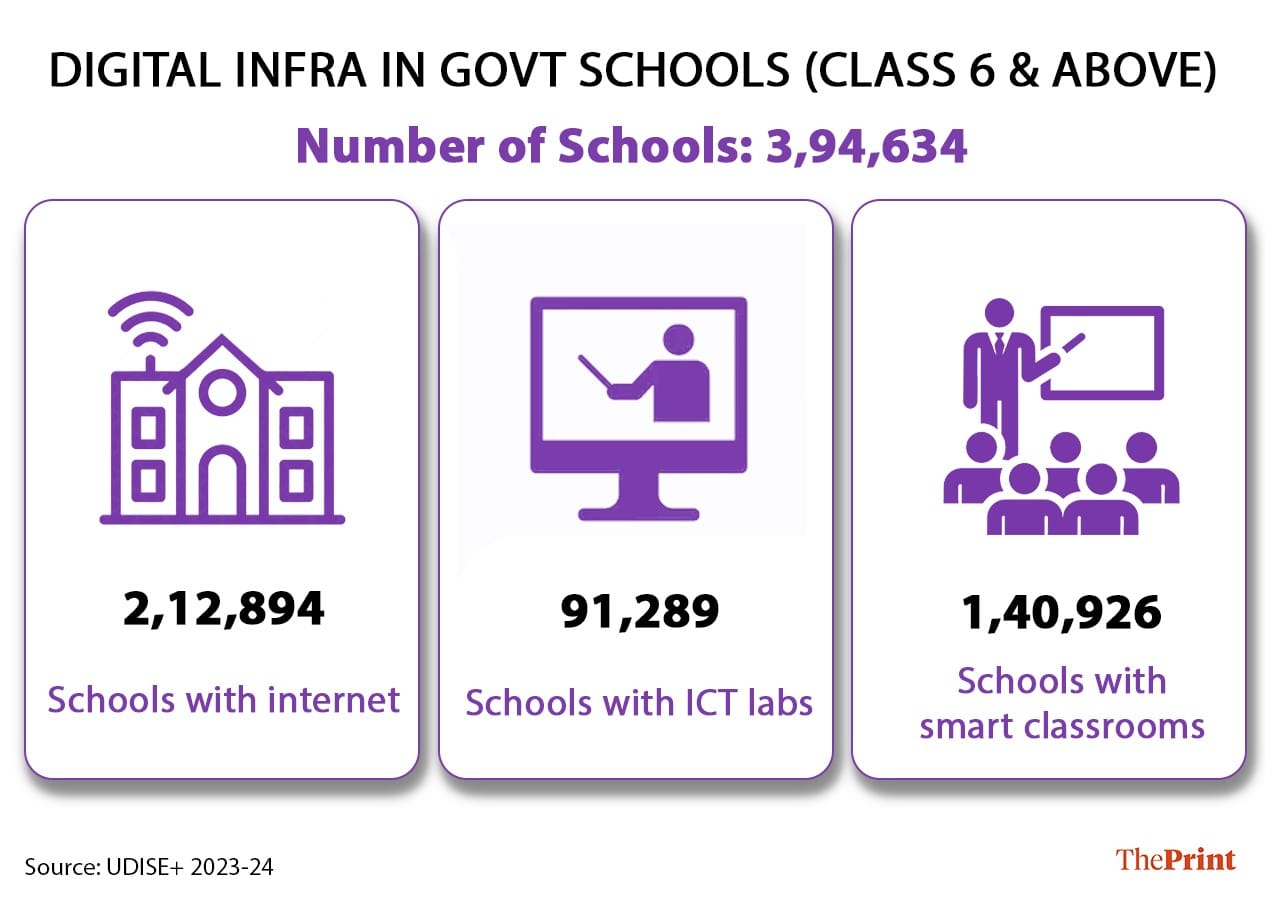

Due to the digital divide, government schools are also finding it difficult to adopt digital learning as prescribed under the policy. “Most government schools like ours lack functional computers and the internet. How are we expected to use digital tools, like the DIKSHA portal?” Syed Mohammad Inaam, principal of a government girls’ senior secondary school in Ferozepur Jhirka, Haryana, told ThePrint. DIKSHA (Digital Infrastructure for Knowledge Sharing) is a national digital platform developed by the education ministry to serve as a repository of learning resources for school education in India.

Teething issues apart, there has been significant improvement in overall learning outcomes at foundational level since NEP’s launch.

The Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) 2024, released in January 2025 by the NGO Pratham, highlighted significant progress in foundational learning among children in rural India. Similarly, the PARAKH Rashtriya Sarvekshan—formerly known as the National Achievement Survey (NAS)—released in July also showed improved performance among Class 3 students, compared to the 2021 assessment. This report, too, acknowledged the role of NIPUN Bharat in driving these gains.

Shaveta Sharma-Kukreja, CEO and MD of Central Square Foundation, which works in the field of early education, said that FLN is not just an educational goal, but an economic imperative.

“By 2047, 950 million Indians—25 percent of the global workforce—will enter the job market. Of them, 250 million will pass through primary schools in the next two decades. By prioritising FLN, NEP 2020 did what few policies have managed. It realigned India’s education system with the science of learning and the needs of a young, ambitious nation. It placed the youngest child at the centre of reform, and ensured that every child, regardless of background, has a real shot at a better future,” she told ThePrint.

But challenges remain.

Several schools are facing trouble in implementing the six-year age mandate for admission to Class 1. Schools had nursery and kindergarten in which they were enrolling 3 and 4-year-olds. But with NEP 2020 fixing the age limit of six years for Class 1, all schools will now have to add one more class in the foundational stage.

Sudha Acharya, principal of ITL Public School in Delhi’s Dwarka, said, “To add another class, schools will need additional classrooms—and many simply don’t have the space. More staff and infrastructure, including support from the board, will also be necessary. We have already built four additional rooms, but many schools are facing challenges. Also, many students who are supposed to come in Class 1 are not 6-year-old yet. What do we do in such cases? We are still awaiting some clarity.”

Changes in assessment

The policy emphasises continuous, multidimensional assessment of students, rather than relying on a single high-stakes exam, with the aim to discourage “rote learning”.

In line with the same, PARAKH (Performance Assessment, Review, and Analysis of Knowledge for Holistic Development), a body established under NCERT, designed the Holistic Progress Card (HPC) framework, which will be in digital format, which takes into account feedback from peers, parents, and self-assessment of students to track their progress throughout the year. According to latest data by PARAKH, 26 states and UTs have either adopted HPC up to Class 8, or are in the process of doing so.

But while many private schools have adopted the framework, government schools are still “not even aware of HPC’s existence”. “To adopt it, we first need proper digital infrastructure,” said Dinesh Chandra Sharma, president of Uttar Pradesh Teachers’ Federation.

For the secondary stage, NEP 2020 suggested eliminating the ‘high-stakes’ aspect of board exams. In June, CBSE announced a two-phase board exam policy for Class 10, starting with 2026 exams. The first phase, mandatory for all students, will be held in February–March, followed by the second in May, which will be for those who receive a compartment in the first, or want to improve in up to three subjects.

The two-exam policy has, however, raised concerns over logistical challenges.

Aditi Misra, director of Delhi Public School, Sector 45, Gurgaon, appreciated the intent behind the move, but noted that practical challenges are significant.

“From a school’s perspective, this will mean twice the planning, preparation, and evaluation effort—not to mention the emotional load on teachers and students. For it to succeed, we’ll need additional support, training, and infrastructure. There’s also a risk that well-resourced schools may cope more easily, widening the gap with others, unless the system is made more equitable,” she told ThePrint.

NEP in colleges & universities

NEP 2020 envisions flexible undergraduate programmes of up to four years, offering multiple entry and exit options. In 2021, the University Grants Commission (UGC), India’s higher education regulator, issued guidelines to operationalise this model, under which, students can exit after one year with a certificate, after two years with a diploma, three years with a degree, or four years with a degree with honours and research.

The policy recommended a one-year masters programme after a four-year degree, and discontinued the MPhil degree.

To support this structure, UGC launched the Academic Bank of Credits (ABC) in 2021 on the first anniversary of NEP 2020. The ABC serves as a digital repository that records and tracks the academic credits earned by students across institutions. Additionally, the UGC introduced the National Credit Framework (NCrF), which allows the ‘creditisation’ of all forms of learning—formal and informal—based on proper assessment.

This means students can earn academic credits not just through classroom instruction, but also through laboratory work, online courses, innovation labs, sports, yoga, physical activities, performing arts, and more.

Former UGC chairperson M. Jagadesh Kumar said that prior to NEP 2020, India’s education system was rigid and compartmentalised, but now it is being reoriented to promote student mobility, digital integration and academic flexibility.

“With the introduction of mechanisms, like ABC and NCrF, students can enter and exit their educational journey without losing prior learning. This signals to students that education is a continuum, not a closed door. The new four-year undergraduate framework now accommodates research, vocational skills, flexibility, and clearly defined exit options,” he told ThePrint.

More than 200 higher education institutions have adopted the four-year programme so far.

However, several institutions, including the University of Delhi (DU), are facing major infrastructural challenges as they prepare to welcome the first batch of fourth-year students on 1 August.

A.K. Bhagi, president of DU Teachers’ Association (DUTA), said that the majority of the university colleges are struggling to accommodate an additional batch of students. “Colleges need extra infrastructure, more teachers, and financial support to upgrade their facilities. Otherwise, this smooth transition is not possible,” he said.

Common entrance exam

NEP 2020 envisioned a common entrance exam to replace the multiple, separate tests conducted by individual universities—aiming to significantly reduce the burden on students, institutions and the overall education system. The UGC introduced the Common University Entrance Test (CUET) for undergraduate and postgraduate admissions in 2022.

The test, conducted in online format by the National Testing Agency (NTA), completely overhauled the admission process for universities, even as there were several infrastructural challenges in its initial year, with multiple sessions being cancelled due to technical and digital issues.

According to former UGC chairperson Kumar, while CUET initially challenged existing inequities, it quickly created a more level playing field. “For the first time, students from tribal districts, rural schools, and non-elite urban institutions could access the same admission process as those from historically privileged systems,” he said. “CUET is creating a fairer starting line for students from diverse backgrounds by disrupting the old pattern of exclusion based on inconsistent marking systems.”

The introduction of CUET has received mixed reactions, with some DU faculty members claiming that it has led to vacant seats. Naveen Gaur, associate professor of Physics at Dyal Singh College, said that his college has 2,200 sanctioned seats for third-year admissions, but only around 1,600 students enrolled. “In the second year, the gap is around 20 percent. A centralised single test system doesn’t work for all colleges. It benefits elite institutions and popular courses. For less sought-after courses, students often don’t apply through such centralised tests.”

‘Dilution of courses’

A section of teachers has alleged that the changes in course structures and curriculum under NEP 2020 have diluted the “core papers”. Several universities have introduced short term credit-based Value Added Courses (VACs) to promote multidisciplinary learning and provide students with skills beyond their core academic subjects.

DU offers a variety of VACs, including Ayurveda and Nutrition, Yoga, Fit India, Vedic Mathematics, and courses on the Bhagavad Gita.

Gaur said that the time devoted to core papers has not been adjusted to accommodate these generic courses. “The VACs are not useful at all. They’re just weakening the students’ academic foundation.”

Teachers at Delhi’s Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) have raised similar concerns. “They (VACs) offer no additional value to students within their core disciplines,” said Moushumi Basu, an associate professor. The university has introduced VACs in subjects like Yoga and Wellness, Indian Knowledge Systems, Thinking in Sanskrit, and Environmental Science, among others.

Under the policy, students who complete a four-year undergraduate degree with research with 7.5 CGPA are eligible for direct admission into PhD programmes, without requiring a master’s degree. Tanvir Aeijaz, associate professor of Political Science at DU’s Ramjas College, said the removal of the traditional academic pathway—two years of Masters and two years of MPhil—will weaken the foundation for PhD students.

“The kind of depth and specialisation that came with a two-year Masters programme is simply missing in the new four-year undergraduate degree. Earlier, students were rigorously trained in core and elective areas, followed by a dissertation in MPhil that prepared them for serious research. Without that, we’re going to see a dilution in the quality of PhDs,” he said.

But ex-UGC Chairperson Kumar said that the four-year honours programme preserves the depth of a major discipline through advanced coursework and research, while also allowing students to engage with knowledge beyond their core field.

Internationalisation of India’s education system

The government has also taken several initiatives to internationalise the country’s education system, in line with NEP 2020’s recommendation to promote India as a global academic destination, and restore its role as a “Vishwa Guru”, encouraging high-performing Indian universities to set up campuses abroad, and inviting selected top global universities to operate in India.

IIT Madras launched its Zanzibar campus in 2023. IIT Delhi has set up a campus in Abu Dhabi, and IIM Ahmedabad is expanding to Dubai.

Following the recommendations, in November 2023, the UGC (Setting up and Operation of Campuses of Foreign Higher Educational Institutions in India) Regulations were notified, allowing the top 500 universities worldwide to apply to set up campuses in India, and launching a dedicated portal for this purpose.

Last year, UK’s University of Southampton became the first university to receive UGC’s approval, and is now setting up a campus in Gurugram. The University of Liverpool has also received the nod for a campus in Bengaluru. Two Australian universities also set up their campuses in GIFT City, Gujarat, in accordance with International Financial Services Centres Authority (IFSCA) regulations.

Besides, the UGC’s joint, dual, and twinning degree regulation has also helped over a hundred Indian institutions collaborate with foreign universities to create mutually recognised programmes, where a student could spend some time in India and the rest abroad.

“With internationalisation, there are many tangible benefits for Indian students, such as cost-effective global exposure, credit mobility and flexibility, diverse learning ecology and global credentials without moving out of India,” former UGC chairperson Kumar said.

(Edited by Mannat Chugh)