The New Education Policy (NEP) introduced by the Modi government has brought welcome change on some fronts: It has envisioned multidisciplinary learning in higher education, floated a common college entrance test in place of today’s cacophony of exams, and promised spending on education at 6 percent of GDP.

But let’s leave all this aside for a bit and talk about the elephant in the room: English instruction. In line with its passion for linguistic nationalism, the government has said that it would like the medium of instruction to be in the student’s mother tongue (or local regional language) until at least Class 5.

This is not new. For years, India has seen a long-running battle against English on misplaced sentimental grounds, including national pride and anti-colonial fury. More recently, the war on English has become a cornerstone of populist politics: English is the preserve of the ‘intellectual elites’, some populist politicians say.

The language war has been on since as early as the 1950s. Against much resentment at the time, Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru fought to include English as one of India’s official languages. In the decades that followed, that policy reaped dividends. As much as people hate the British Empire, English is today the only really global language; it dictates global business, politics and even knowledge creation.

Also read:India’s New Education Policy takes the bullet out of the old, Russian roulette-like system

And the knowledge of English put India in a unique position.

While most other developing countries made their wealth through the manufacturing sector, India’s late economic bloom depended on the export of high-end services, such as information technology, pharmaceuticals, and even retail and hospitality. In the 1990s and 2000s, India’s equivalent of Chinese factories was call centres, which pulled in hundreds of thousands of young English-speaking graduates from second-tier towns and even villages. Heavy investment in technical education through the early decades of India’s independence also created a rich pool of engineers, who attracted foreign investment from multinational companies that were looking for inexpensive quality labour. Similarly, Indian scientists created the developing world’s most accomplished space agency – the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO).

The role of English in all these was heavily underplayed but integral: English made it possible for Indians to access knowledge from around the world more easily. It allowed Indians collaborate with businesses everywhere and sell services to global markets more competitively. As Jack Welch, the late Chairman of General Electric put it, “India is a developing country with a developed intellectual capability.”

English also spawned the growth of a remarkably influential diaspora: Unlike other Asians, Indians assimilated quickly and easily wherever they travelled, lived and worked – in large part, due to their multilingual capabilities and knowledge of English.

Countries that run on manufacturing can, to some extent, afford linguistic nationalism. Folks in manufacturing jobs don’t need to transact with – or speak to – people from foreign cultures on a daily basis. But India is likely never going to develop a manufacturing sector; its geography and polity are simply too complex to provide for easy allocation of land resources and efficient bureaucracy – the pre-requisites for manufacturing.

Yet, a services-fuelled boom – albeit against historical odds – is not beyond India’s reach. India has already shown the ability to send people several rungs up the social mobility ladder within a generation. ISRO’s Chairman K Sivan, for instance, is the son of a farmer.

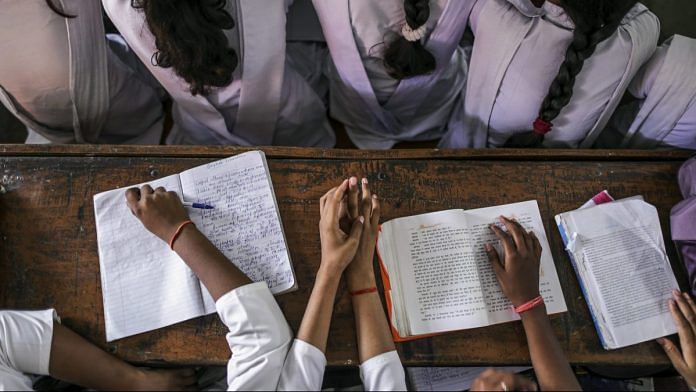

The primary reason India hasn’t been able to scale up its services-fuelled growth story so far is that it hasn’t managed to deliver quality education – including in English – to the masses, which would have enabled them to compete globally. It makes no sense today to deprive future generations of English proficiency. By waging a war on English, India is squandering away its demographic dividend and depriving its youth of global opportunities.

Some people argue that children learn better in their mother tongues. But in truth, mother tongues are not genetically transmitted; languages are learnt around the ages of 3-4 and beyond. That means, in order to develop English proficiency, children should be instructed in English at the preschool level.

The NEP’s insistence on regional languages through primary school flies in the face of this science. As children get older, they find it progressively harder to pick up new languages – and that puts such students at a significant disadvantage in university, where they must spend more time figuring out English than on learning the subject that they are there to learn. Worse, as students graduate out of university, they will find it harder to compete for jobs in the global market or pursue higher education abroad.

The result of all this is quite simple: Class-based inequality will widen in India, as those who are able to afford posh English-medium education in the cities pull further ahead of talent from the hinterland.

In recent years, even the Chinese have begun to agree. For most of history, China has been among the most culturally protectionist countries on earth – and its attitude towards English was no different. Yet, a 2017 report pointed out that China now leads the world for the number of English-medium international schools. And that market continues to grow: Studies have found that the demand for English education is high amongst the Chinese, even at the primary school level, owing to the global opportunities that it opens up.

Some critics would argue that the emphasis on regional languages is useful because it is difficult to find quality English teachers to teach other subjects. But countries like China have been filling that gap by engaging young graduates from the West, who travel and teach across China for a year or two out of college. This is a policy worth replicating in India. Besides, India is already well ahead of the rest of Asia in this regard; it can engage young teachers from within its own urban middle class for the purpose. The government should be looking to develop a programme to involve them.

The war on English might make political sense, but it betrays India’s natural economic strengths. This is bad news for India’s demographic dividend.

This article was originally published in Freedom Gazette.

Also read: A second shot at boards, no MPhil, a blow to rote-learning — what Modi govt’s NEP brings

I think learning a language also help in developing critical thinking. Three language formula will not burden a child. Language is something which a child should learn as early as possible. Mathematics, Languages, Literature etc. are the most important topics for a student till 5th Class. Literature helps in developing communication skills. And learning atleast 2 languages does give a broad knowledge of communication and understanding a context. Understanding the context is a very fundamental and important skill which Modern India requires.

Child learns to recognize the sounds made by the members right from birth. Then it identifies the objects and actions by their names even at age just about one year. No education from parents can make the child learn these primary structure of language. Psychologist and linguists have studied how children learn. Each child even provinces new words associating them with specific meanings and parent are required to discover the meaning of those words. For a few days it is a joy to parents to use these words while talking the their loved children. They don’t hasten to correct them.

The point is that child learns by observing and hearing the persons among whom it is spending time. A child whose family speaks some language other than English communicates many abstract concepts through conversation to their children. The school education does not cover all those concepts with practical situations for the children to grasp intuitively the abstract concepts. That is why it is said that children imagine and think in their mother tongue. The abstract concepts are developed in association with the words of mother tongue. But at homes the talk is restricted mostly to basic activities of day to day life and some special fields which the family members discuss. So to have wider and deeper exposure children have to learn the meaning of words which they have not come across earlier and the language the better for their progress.

This should make it clear why it is better to have primary education in mother tongue and English also should be taught from secondary and tertiary level so that the thought process of the child evolves gradually to accommodate the suttle nuances of concepts only familiar from English usage.

If we hear a learned discussion on any topic we find speakers include many English words. That is mostly because the vernacular languages have no exact substitute in currency.

So we should not look at the new education policy as a conflict between Nationalist ideas and utilitarian ideas. Purely from the point of utility also the policy is justified.

This is a well written and researched article. Thought countries like Japan Germany can use their national languages, same can’t be applied to india since there are lots of languages. Hindi can’t be used for obvious reasons. So the only best option is English. I would recommend every Indian to learn English and their mother tounge/regional language. That’s more than enough. Learning 3 languages increases the burden. And medium of instruction must be English. It’s easy to learn English and it’s the global language for knowledge transfer. So medium of instruction must be in English

Compulsory vernacular state language education was a good step forward. Most of this ethno-linguistic tensions occur in India when Hindi speakers go to a non-Hindi speaking state and don’t learn the state language.

If they are poor, they enroll their children there in a Hindi-medium school and if they are middle-class, their children are enrolled in a English-medium school with Hindi as 1st (or 2nd) language.

But, I must say that the medium of instruction should be made compulsorily in English after Class 5 (or, even earlier after, say, Class 3?) because India needs a common medium of instruction from middle school onwards to create a common talent pool on the country.

Of course, the said language can’t be Hindi because of obvious reasons. Most importantly that it will give undue advantage to pupils whose mother tongue is Hindi. So unless Modi government can push through Sanskrit as that common medium, English is the substitute.

Nonsense based on the unsubstantiated claim that languages are learnt around the age of 3-4. The truth is that babies start learning and absorbing from their surroundings from birth. Children can speak simple words from the age of 2. Nobody is waging a war on English. It’s just not needed to be learnt as the first language. The truth is that except for a microscopic minority the vast majority has not benefited from this English policy. Most developed countries be it Japan, Russia, U.K, Germany, France and even China have developed knowledge in their own languages which can then be transmitted down the pecking order because of a common language. In India this is simply not possible because those at the top are unable to communicate in the same way because of the linguistic handicap. As for software programming Israel and Russia produce equally good if not more technically competent personnel in Hebrew and Russian. Israel has revived Hebrew a nearly extinct language. The truth is that despite this emphasis on English India is still a desperately poor country at the bottom of every HDI index. Language is a reflection of the local culture, it’s genius and traditions. It is literature, poetry, emotions and much more. India before British rule was one of the richest countries in the world and never used English. As long as we continue to emphasise English India will always remain a nation of copycats producing nothing original, developing no new knowledge and good only at reproducing what it receives from elsewhere. A nation of call centres speaking in English.