New Delhi: Hardly three years old, Ishika Sarsar clings to her 10-year-old brother Gaurav as he tries to control their new puppy. While he attempts to handle both, Ishika slips through his arms and falls, her head hitting the sofa. The colour drains from Gaurav’s face, but Ishika doesn’t cry. He rushes to fetch some ice to apply to his little sister’s head.

“He is always extremely vigilant around her and she understands his emotion behind it,” says Shweta Sarsar, their mother, at their home in Delhi’s Burari. “Ours used to be a very happy and loud household. Now we have got the puppy to just make the children laugh.”

On 12 October 2020, tragedy struck the Sarsars when they lost two daughters, Gunjan (8) and Bhumi (5). A speeding Honda City with a 17-year-old behind the wheel hit the two girls, who had stepped out with the entire family for ice cream. The accident took place very close to their previous home in Rana Pratap Bagh.

Gaurav, who was 6 years old at the time, and Milap Singh, a family friend of the Sarsars, were severely injured in the accident, but survived.

“The boy (minor) was using his mobile phone and was speeding,” says Jaspal Singh Sarsar, the girls’ father, who works as a cleaner at Delhi University. ThePrint has also accessed an audio recording, purportedly of a conversation between Jaspal and the juvenile’s father, where the latter allegedly admits that his son was using his phone at the time of the accident.

The Pune Porshe accident case that left two young techies dead has put the spotlight on similar accidents caused by minors. After the Pune incident and the subsequent arrests of the minor’s parents and two doctors accused of replacing his blood samples, there was widespread outrage about how money and privilege can be used to manipulate the system, while justice becomes a casualty.

There have been past instances where investigating agencies have pushed for a juvenile perpetrator to be tried as an adult, but both the Supreme Court and Delhi High court have ruled against it, noting that the crime doesn’t fall under the category of “heinous” offences.

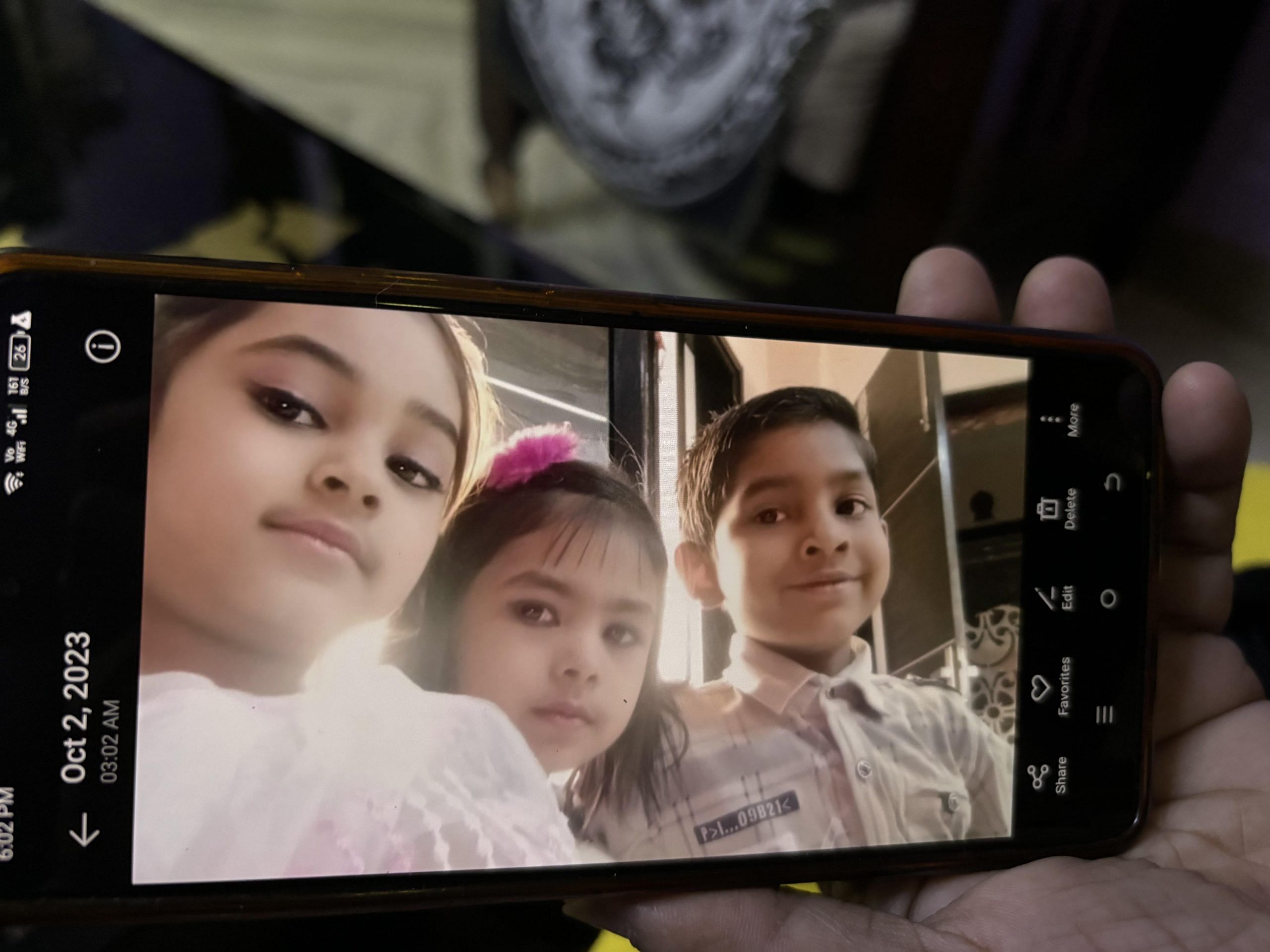

Gazing at her toddler, who was conceived 11 months after Bhumi and Gunjan (who was also called Ishika at home) died, Shweta says, “We named her Ishika because looks like her elder sister. We felt like Gunjan has been reborn.” She scrolls through her phone, showing the numerous pictures of her children, smiling.

Four years have passed since the accident, but the family still feels they are stuck in time, their efforts to move on slowed by a long wait for closure. To add to their misery, the minor, according to police sources, was never sent to an observation home after the accident.

The family was even unaware that the criminal case against the minor was terminated on 11 October, 2021. A separate case is ongoing at the Motor Accident Claims Tribunal. The next hearing is on 7 July.

Also Read: Weeks after Pune Porsche case, Delhi lawyer rams his Audi into 2 rickshaw pullers, 1 dies

How minor was let off & what the law says

The 17-year-old was booked under IPC sections 279 (rash driving or riding on a public way), 337 (causing hurt by act endangering life or personal safety of others) and 304A (causing death by negligence) by the Model Town (North West district) police on 13 October 2020, a day after the accident.

The car, according to police sources, was registered in the name of the minor’s uncle, but was being used by his father. In such cases, legal action may be initiated against the minor’s guardian under sections of the Indian Penal Code and the Juvenile Justice Act, while the owner of the car may also be booked under the Motor Vehicles Act. However, no such arrests were made in this case.

The teen was apprehended by the police on 14 October, two days after the accident, and then handed over to his father. He was produced before the Juvenile Justice Board (JJB) the next day, and then released, with his father signing an undertaking.

“We didn’t know that the criminal case had been closed. No one told us about it. We are not very educated and don’t understand the law. We thought that if we don’t settle, the minor or his family, who let him drive the car, would be punished,” says Jaspal.

Under the Juvenile Justice Act, 2015, crimes are divided into three broad categories — petty, heinous and serious offences. While the punishment is three to seven years for serious offences, for heinous offences it is a minimum of seven years. These include crimes such as murder, rape, dacoity etc. A petty offence refers to crimes that warrant a maximum punishment of not more than 3 years imprisonment under the IPC or any other law.

All IPC sections that the minor was booked under, including 304A, fall under the category of “petty” offences.

Section 14 of the JJ Act calls for automatic termination of inquiries if the probe against a minor in petty offences remains inconclusive after four months and a maximum extension of another two months from the day the minor is produced before the JJB.

Speaking to ThePrint, advocate Sushil Tekriwal explained that under the JJ Act, termination can take place on two major grounds in case of petty offences — if the inquiry remains inconclusive after four months and the additional extension of two months, and if the merits of the case which are evaluated based on circumstances, don’t hold during the inquiry, for instance, if it is a case of contributing liability, meaning both parties shared responsibility for the accident.

“Time limit for the finishing of the inquiry by the JJB is an extremely crucial part of the Act. For petty offences, the law mandates that the JJB is required to complete the inquiry within four months and this may be extended up to six months. However, if any inquiry is pending or has remained inconclusive even after the additional term, the case shall be terminated,” Tekriwal said.

The lawyer further said, “In petty offences, the merits of the case depend mostly on circumstantial study, that is under what circumstances was the offence committed. Either the magistrate presiding over the matter can view it and decide upon it, or a committee can be formed and a report has to be filed on the matter within the stipulated time period.”

The exact reason for the termination of the 2020 case is not known. Because the case involves a minor, these details are confidential.

Speaking to ThePrint, the juvenile’s father said, “He continues to feel guilty about what happened. The case was terminated because he is a minor and it went on for a year. We had to pay a fine after which he was let off by the JJB.”

According to a senior Delhi police officer, in 304A cases, even adults get bail easily. “Termination of these kinds of cases is quite common. Sometimes, the minor is let off with a warning or simply with a fine,” this officer told ThePrint.

In October 2021, the Delhi High Court had ordered that cases of petty offences against juveniles which have been pending over a year or have remained inconclusive should be terminated immediately.

Section 14 of the Juvenile Justice Act warrants the need for counting of the four-month period from the day the juvenile is produced before the JJB. Yet, delays still occur because a substantial period of the inquiry in such cases is dedicated to determining the age of the child. Moreover, matters further get stuck at various stages, increasing pendency and elongating the judicial process for minors.

The court had also noted that due to the Covid-19 outbreak, juveniles were not being produced before JJBs at all, either in person or via video-conferencing.

In 2019, the Bombay High Court had said that the Juvenile Justice Act is a “reformative, not retributive” law.

Also Read: Pune Porsche case wouldn’t have taken a U-turn for the rich family if not for public outrage

The accident

On 12 October 2020, Jaspal’s younger sister had come to visit the family, so they decided to head out for ice cream at around 10.30 pm.

“We had planned a small outing, the three kids, my wife and mother. First we went to the gurdwara and then we picked up Milap Singh, my father’s friend. We picked up some medicines for my mother and then stopped for CNG. Near the CNG station, the kids went with Milap for some ice cream. The speeding car came suddenly and hit all four of them. We saw the kids flung into the air,” Jaspal recalls.

While Milap Singh fell on the ground, Gaurav, Bhumi and Gunjan were tossed into the air.

“Gunjan and Bhumi went under the cars on the road. I had to pull them out. Bhumi was still conscious but Gunjan’s face had been smashed. A Sardarji from the area gave us a lift. Gunjan was on my lap and we went from hospital to hospital. The first few hospitals said they weren’t equipped to treat such a serious patient. Bhumi and Gaurav were with their mother in a police car,” says Sunita Devi, Jaspal’s mother.

Shweta says the minor’s family never apologised to them. “We don’t want any money. Ask them to give their son, we will forgive them. The boy and his parents never even asked for forgiveness. I am a mother, I would have still forgiven them if they had asked for forgiveness.”

After the accident, the family shifted to Burari. Just three months after they’d moved into the new house bought using money Jaspal’s father received upon retirement, they were struck with another tragedy. Suresh Kumar, who worked with the Child Welfare Committee (CWC), “died from grief” after losing his two granddaughters.

“He couldn’t take it. He went quiet after the accident,” says Sunita Devi. The family now barely manages to make ends meet with Jaspal’s cleaning job which fetches him only Rs 15,000 per month.

There are no photographs of Gunjan and Bhumi on the walls of their home. “We don’t want Gaurav to grieve every day. It would have been a constant reminder. After the accident, he had lost consciousness for a week. He takes time to speak,” says Shweta, showing the fading marks of the cuts Gaurav sustained during the accident on his forehead.

To this, Gaurav says, “I will tell Ishika about her sisters when she grows up.”

(Edited by Gitanjali Das)

Also Read: Pune Porsche case: Can the 17-yr-old accused be treated as an adult? Here’s what the law says