New Delhi: Namita Gupta first met P.G. Wodehouse in a crowded Delhi street on a hot Sunday afternoon. A few minutes later, she bumped into Haruki Murakami.

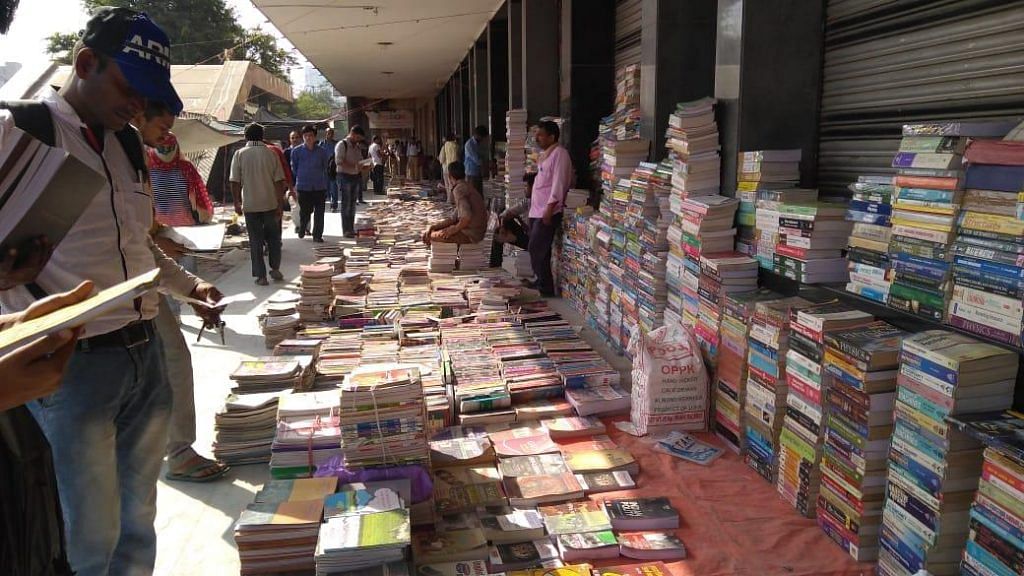

For Gupta, a 24-year-old postgraduate in English literature from Shiv Nadar University, these meetings during her early years were fated to happen — having grown up in Daryaganj for much of her childhood, she spent every other weekend traversing the length between Delite and Golcha cinemas to browse books sold at throwaway prices at the iconic Sunday book market.

“I pursued English literature because of Daryaganj,” she tells ThePrint.

“It’s where I’d spend hours carefully sorting through thousands of books — Enid Blyton’s collections to Nancy Drew and Hardy Boys, Charles Dickens and Jane Austen as I got older. Daryaganj has played an important role in allowing me to engage with a wide variety of ideas — specially because books came at affordable prices.”

From Batman graphic novels, discounted NCERT textbooks, dictionaries, folktales in regional languages to a host of international writers, the Sunday Patri Kitab Bazar at Daryaganj in Delhi has, for many, been an introduction to the world of literature.

Now, that chapter seems to be coming to a close, as a few weeks ago, the Delhi High Court directed the North Delhi Municipal Corporation (NDMC) to shut down the Sunday bazaar from Netaji Subhash Marg — declaring it a no-hawking zone. The court order cited impediments to vehicular and pedestrian movement.

In a singular moment of administrative action, a 50-year-old tradition was demolished.

“The order put 276 book vendors immediately out of employment which also means ancillary labour in the book business — in the form of transportation, bulk sellers and others — equalling close to 2,000 people who were left in the lurch,” Ashrafilal, a vendor and Daryaganj Patri Sunday Book Bazar Welfare Association vice-president tells ThePrint.

Days after the order was passed, the book association and hundreds of its members marked the first Sunday that they were prohibited from setting up shops as a dark day in Delhi’s history.

On 27 July, the vendors gathered for a strike at Daryaganj, hoping to make their plight visible to local authorities. The resistance hasn’t worked. Ashrafilal and Qamar Sayeed, president of the book association, tell ThePrint that “the government took a stand against democratisation of learning and education”.

“We are proud of what we do. We provide cheaper alternatives for a poor country starving to learn. They say ‘Beti Bachao Beti Padhao,’ but where else are people going to get a book worth Rs 100 for Rs 10 in Delhi? asks Sayeed.

‘Order didn’t follow due process’

According to reports, the order — which came in July — was based on an account submitted by the Delhi Traffic Police to the high court. The traffic authorities had argued that the book market was adding to congestion in a high-volume traffic zone and forcing pedestrians off the sidewalk into a bedlam of cars and rickshaws.

The NDMC acted quickly, notifying vendors merely days before the Sunday market was to hit the streets — an action that vendors say directly violates the central government’s Street Vendors (Protection of Livelihood and Regulation of Street Vending) Act, 2014.

The Act, which reads “No street vendor shall be relocated or evicted by the local authority from the place specified in the certificate of vending unless he has been given thirty days’ notice for the same in such manner as may be specified in the scheme,” was seen as a win in a long-standing battle for authorities to recognise the legitimate role of informal and small-scale vendors in the Indian economy’s supply chain.

“No due process was followed this time,” Sayeed says. “We were told three days before, ‘You can’t set up your stalls anymore,’ and obviously if they’re going to send trucks and officials to physically stand in our way, there’s no option for us but to remove our stalls.”

This isn’t the first time that Daryaganj has been the target of convenient gentrification. In January last year, the Sunday book market was sacrificed for up to five weeks as “a part of the ongoing beautification drive in the run-up to the three-day Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Summit to be held in Delhi,” the Hindustan Times reported.

There was also a closure in 1990, but thanks to citizens’ efforts, including letters to the PM from concerned residents, the market was reopened.

Further, the NDMC’s clampdown might end up being technically illegal as the association has merit to fight for ‘heritage status’.

“Natural markets where street vendors have conducted business for over 50 years shall be declared as heritage markets,” the 2014 Street Vendors Act reads, “and the street vendors in such markets shall not be relocated.”

However, according to Vinita Reddy, the city superintendent of NDMC, none of the vendors has approached officials with these claims, “either of demanding ‘natural market’ status, or of any violation of the Act when it came to notifying them”.

“It was declared a no-hawking zone by the law, so that section (about adequate notice) doesn’t apply,” she tells ThePrint. “The only dialogue between vendors and the NDMC right now is about where to resettle them, and because of in-fighting and internal disagreements, in fact it’s the sellers who have asked for more time to meet us.”

Reddy adds that she “doesn’t want to see an old market like this go”, and that all parties are “seeking a permanent solution to the problem,” rather than a temporary fix.

Lastly, “whether or not it qualifies as a natural market is a decision for the Notification of Town Vending Committee (TVC) to take,” she adds.

Also read: What the girl in the pink burkha taught me about life and loss in Old Delhi

The end of an era

Nestled between several historical buildings in Delhi, and a stone’s throw from the busy lanes of Chandni Chowk, the Daryaganj Sunday book market was more than just a buyer-seller place for books. For many, it was a marker in Delhi’s cultural memory and for them it is a classic case of paradise making way for a parking lot.

Meenakshi Reddy Madhavan, a 37-year-old author can’t help but feel a sense of profound loss on hearing the news.

“What a shame — as the city gets colder and harder, and everyone is talking about economic slowdowns, climate change and the politics of hate — to stop something that brought so much joy to so many peoples lives,” she tells ThePrint.

“For many, it was a way to discover books, and to own them, without the expense of a bookstore or access to the internet. By taking it away, you’re taking away something deep, like cutting down an ancient tree and calling it progress,” she adds.

Popular Facebook page Humans of Hindutva had an angrier reaction.

“It’s not really just a physical space, it’s an event,” says Siddharth Singh, instructor of critical thinking at Ashoka University.

“You have to carve time out for it — take a water bottle, be prepared to spend hours walking. Honestly, Delhi is no longer built to facilitate pedestrian movement, and open-air markets like Daryaganj, where you can see historical buildings and go over to Chandni Chowk for lunch, are important for a sense of cultural connection,” he says.

Contrary to the police’s concerns about pedestrian safety, book-lovers like Singh believe that “gentrification shouldn’t come at this cost. Daryaganj didn’t make walking difficult, in fact, it made you leave your car at home”.

“The moment you say the name Daryaganj, the other person replies ‘The book market!,’ Gupta adds. “It’s like shutting down a city landmark, like saying…‘Oh this monument is getting in the way of building a highway, so let’s tear it down’.”

For Madhavan, who used to set off for the book market with her mother on Sunday mornings in a cycle rickshaw, Daryaganj added to her sense of “Delhiness,” allowing her to find belongingness in “people like us — soft-voiced and delighted-looking readers, mostly students looking for engineering textbooks, but enough ‘real’ readers that you realised you weren’t alone.”

The road ahead

Now, vendors say that NDMC officials are helping them scout for new areas to settle down. So far, they have presented them with three options, all of which come with significant challenges of their own.

Children often play cricket in the evenings at the Ramlila ground.

“The area near the Pracheen Hanuman Mandir in Jamuna Bazar is infested with miscreants, drug addicts and also has too many vegetable stalls,” Sayeed says.

A closed banquet space in the Kaccha Bagh Area of Chandni Chowk “will mean that it will feel more like a weekly mela, where our old customers just won’t come”, he adds.

Daryaganj, it appears, has become intrinsically linked not only to what vendors sell, but the dignity with which they sell it and the pride they take in their work.

“There was a girl from Noida, who came to me one day and said that she ranked 14th in her IAS exam,” Ashrafilal tells ThePrint. “She used to buy her books from here.”

Also read: Humayun, Safdarjung tombs in Delhi among 10 monuments that will now remain open until 9 pm