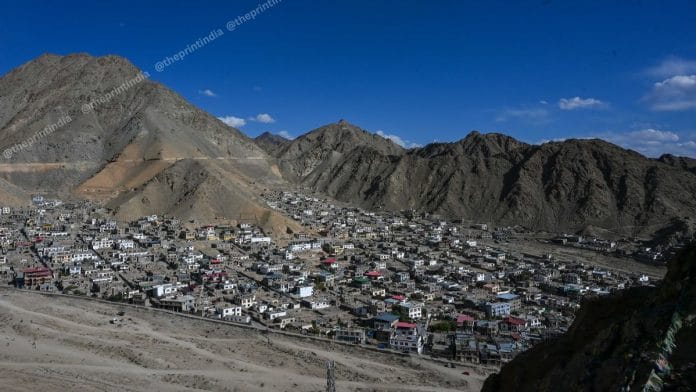

Leh: The streets of Leh have gone quiet since the violence of 24 September that claimed four lives, including that of an ex-serviceman, but the tragic memory lingers amid relaxed curfew conditions. The walls still whisper the defiant plea: “Sixth Schedule for Ladakh. Save Ladakh Himalayas.”

By the Maney—the Buddhist prayer wheel next to the ground where the now-jailed activist Sonam Wangchuk and others sat on hunger strike last month, voicing the demand for statehood and the Sixth Schedule for Ladakh—67-year-old Jigmet Angmoo stands with a quiet fire in her eyes. “We need the Sixth Schedule to protect us, the tribals,” she says, her steady voice echoing off the mountains. “They gave us a Union Territory without a legislature… What did they expect? The mainland thinks tribals are stupid. Not many of us have fancy degrees, but we know when to rise for our land, our water, our environment, and our culture.”

The anger still reverberates in the villages of Chuchot Shama, Stok, as well as the remotest of areas, like Changthang, home to the Pashmina goat herders. Residents fear that without constitutional safeguards, outsiders can occupy their land, leaving the already fragile ecology of the region at risk due to “industrial lobbies and mining” and “unchecked tourism”, and that the tribal community’s interests will continue to be overlooked.

Since 2019, most Ladakh residents have voiced resistance to proposed or ongoing infrastructure and development projects, despite the Centre’s assurance that the UT administration is committed to bridging gaps. While the government has said that these projects boost connectivity, jobs and economic growth, the people of Ladakh argue they also risk erasing cultural identity, land rights and ecological balance.

The projects include the Solar Energy Corporation of India (SECI)-led 13-gigawatt solar park on Pang plateau, Power Grid Corporation of India’s 713-km transmission corridor to evacuate power to the national grid, Zojila Tunnel and Shinku La Tunnel, road widening projects in Changthang, hydroelectric projects, and industrial tourism infrastructure in sensitive high-altitude zones. Over 1,670 km of roads in the region have been newly built or upgraded since 2019, according to official figures.

But local residents say that they were not involved in the decision-making process with respect to such projects—something that the Sixth Schedule would guarantee.

2019 and since…

With the abrogation of Article 370 in 2019, Ladakh was carved out as a Union Territory without a legislature, placing it under direct control of the Lieutenant Governor and the Centre. The high-altitude region comprises two districts—Leh, which is predominantly Buddhist, and Kargil, largely populated by Shia Muslims.

Initially, the people of Leh rejoiced, viewing the abrogation as the first step towards autonomy and inclusion in Sixth Schedule, which would empower tribal communities with a degree of autonomy in governance, and enable them to manage their own affairs and resources, excluding the Shias of Kargil. They thought that the long-awaited freedom from the shadows of Jammu and Kashmir—first under the Dogras, and then the different dispensations in Srinagar—was finally coming.

Demands for Ladakh’s autonomy can be traced back to the 1950s just after Independence, on to the formation of the Ladakh Buddhist Association in the 1970s, before pivoting to the ask for UT status in 1989.

But in 2020, Ladakh residents realised they had lost the protection that they had under Article 370. In 2021, the Leh Apex Body (LAB) and the Kargil Democratic Alliance (KDA) came together to voice the demands for statehood, constitutional safeguards under Sixth Schedule, separate Lok Sabha seats for Leh and Kargil districts, and job reservation for local residents. The Bharatiya Janata Party-led NDA government did make promises of Sixth Schedule inclusion twice—in 2020, ahead of the Ladakh Autonomous Hill Council election, and again in 2024.

Even Wangchuk, who had publicly thanked Prime Minister Narendra Modi on 5 August, 2019, had turned sharply critical by 2023. Calling the UT “a banana republic and a dictatorial state”, he had lamented that everything had gone “astray”, after the Centre barred him from marching to the Khardung La pass.

Centre’s talks with LAB and KDA did commence in January 2023, initiated through the establishment of the High Powered Committee (HPC) on Ladakh by the Ministry of Home Affairs, but Ladakhis had grown impatient over the delay—predominantly the trigger behind last month’s mobilisation. Currently, the talks remain suspended as LAB demands that the Centre restores peace in the region and releases its members, including Wangchuk.

Responding to a question by ThePrint at a press conference in Leh earlier this week, Cheering Dorjay, LAB co-chairman and president of Ladakh Buddhist Association, said, “We rejoiced when Article 370 was removed because without it, we wouldn’t have got UT status. Article 370 was an obstacle to that. But now they have been delaying talks. We have been fighting for identity for 70 years.”

The government did bring in new policies aimed at safeguarding the interests of Ladakh residents this year, like the 85 percent reservation in government jobs for local residents, reservation of one-third seats for women in Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Councils (LAHDCs), and domicile restrictions. But the people say their core issues of Sixth Schedule and statehood remain.

According to the Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) 2022-23, Ladakh’s unemployment rate is 6.1 percent, higher than the national average of 3.2 percent. The government said in response to a question in Parliament in 2023 that Ladakh also registered the sharpest increase in the number of unemployed graduates in India between 2021-22 and 2022-23, over 16 percent in a year.

Also Read: Leh Apex Body says no talks until peace restored, govt’s delays turned Ladakh into pressure cooker

Anxiety over ‘unchecked’ development

Most Ladakh residents argue that autonomous governance and constitutional safeguards under Sixth Schedule would allow them to be an active part of the development process.

Wangchuk has held several hunger strikes to draw the Centre’s attention to these issues, seeking regulated and co-opted development to ensure all projects address the local population’s demands, alleging that government projects have been sprawling out since 2019.

Many Leh residents, including those who were part of the 24 September agitation, echo similar sentiments, claiming that outsiders are buying land. However, senior officials, LAB members, as well as Himalayan Institute of Alternatives, Ladakh (HIAL) co-founder and Wangchuk’s wife Dr Gitanjali J. Angmo, say that no outsider has bought land, at least not officially.

The people also fear that with no autonomy and more concrete infrastructure, the mining of the region’s minerals will also increase.

“The glaciers are retreating, and Ladakh is already a cold desert. Outsiders have no knowledge of our ecology. This is a region that shuts down for six months in winters. We experienced exceptionally heavy rainfall this August, too,” 28-year-old Tsering Dorjey tells ThePrint.

Tashi Nurbo Jayo, 37, a YouTuber and former sarpanch of Stok village, says, “For instance, the population of my village is 2,000. What if 5,000 people come and stay here? We have water scarcity, the economy of this place is based on its ecology. When big tourism firms come, where will we go?”

Some locals also say that the Bilaspur-Manali-Leh railway line would expose Ladakh’s resources for big industrialists to launch mining operations at a faster pace as it would increase connectivity. “Why are they building so many roads and railway lines in such a high-paced manner? For outsiders to come in and for industrial lobbies to mine our resources and take them with improved connectivity?” asks Mohammed Hussain, another resident.

‘No paperwork, no promises in writing’

Against the biting winds of Skyang-Chu-Thang in the Changthang plateau, a tent clings to barren plains. Inside, a Changpa (herder community) family of three, from Samad Rakchan area of the valley, huddles up as the wife stirs up some butter tea. The husband, Wangyal, tightens his woollen cloak, fixes his cap and prepares to leave, driving his 300 prized Pashmina goats onto higher altitudes. From Samad Rakchan alone, 50-odd families graze these goats.

Apart from Samad Rakchan, Korzok and Kharnak are the only remaining major nomadic Pashmina herding communities in eastern Ladakh. While some herders have moved to cities to work as tour guides, drivers, etc, many continue to depend on the Pashmina trade.

Many, like Wangyal, now live in constant fear that the 13-gigawatt integrated renewable energy project in Pang will take away their pasturelands, and disrupt centuries-old traditional migration routes. Pastureland will be acquired for the project from Debrik and Kharnak, apart from Pang. However, these nomadic herders have no legal rights and land titles, which heightens their insecurity.

Wangyal says, “We have to keep moving for pastureland. We spent our summers roaming these pastures in Pang—one patch is never enough. There are some 40–50 shepherd families like us, and this is our only source of income. We aren’t educated, we have only learnt this from our forefathers. They haven’t given in writing what will happen to us, or how they will help us after the pastures are taken away. We don’t own this land, but that doesn’t mean they can take it away from us.”

The nomadic families migrate from one pasture to another during the summers, and as harsh winters set in, they settle in temporary shelters, awaiting the next season. Their survival depends on Pashmina goats, which produce the finest Geographical Indication-tagged fleece—used in luxury products globally, which significantly contributes to Ladakh’s economy. It takes the wool of four goats to produce one kilogram of Pashmina.

This Pang project, among India’s biggest such clean energy initiatives, is expected to generate up to nine GW of solar power and four GW of wind power. The electricity generated will be transmitted to a stretch of 713 km, from Ladakh to Haryana, and integrated into the national grid. It is also a major part of India’s 500 GW clean energy capacity by 2030 target, a commitment made at COP26, and estimated to cost around Rs 60,000 crore, covering approximately 48,000 acres of pastureland, now allocated to SECI by LAHDC.

Senior government officials tell ThePrint, on the condition of anonymity, that the local residents’ concerns over livelihood and grazing rights are being taken into account, but the nomads don’t believe so and fear they will lose their means of survival without compensation and employment. The herders allege that the LAHDC, which was supposed to look at their demands, is instead working only for the BJP-led central government, and that the project is moving further without transparency. Calls by ThePrint to Leh Deputy Commissioner Romil Singh Donk, and hill council chairman, Tashi Gyalson, went unanswered.

“Some officials have told us that we will get jobs and compensation. They have also told us we will have grazing rights, and irrigation will be set up for new pastures, but no one knows for sure. We don’t have paperwork,” Ynenging Lamo, another herder with 350 pashmina goats, says.

Wangchuk, too, has raised concerns about the Pang project, maintaining that he isn’t anti-development, but wants locals to be part of discussions. Last April, he had planned the ‘Pashmina March’, which was called off because the authorities had imposed Section 144 in Leh.

“You see all this land and think, ‘What if the government takes some of it?’ It can’t function this way in a place like this. There are cultures, traditions of tribals. Moreover, these massive development projects will have a reverse impact on climate. Only someone from here can understand this. We don’t oppose the security forces taking the land, we never will. But if this is development in the truest sense, then shouldn’t there be more transparency? If this goes on, first the nomads and then tribal communities will be wiped out. For an outsider, it’s a lot of barren land, for us it is our home…it’s everything. This is why we need the Sixth Schedule,” says Tsangay Rangung, a Buddhist monk from the region.

However, not every Leh resident is against these projects. A shopkeeper, who does not wish to be named, says, “I too had pashmina goats, but sold them. If these projects come, they will bring development, business and employment.” On the climate change risk, he has nothing to say.

Also Read: ‘Centre disrespected our patience, anger against BJP’—how smolder turned into blaze in Ladakh

Limited powers, job quotas, growing frustration

Having lost their four J&K assembly seats with UT status but no legislature, the people of Ladakh say that their representation has worsened, leaving them with little voice. The LAHDCs formed with limited power in Leh and Kargil also have fewer powers, as the UT functions under the L-G, with two District Commissioners. Regional leaders and residents describe the current administration as an “absolute muddle”.

Mutasif Hussain, former chief coordinator of Ladakh Research Scholars Forum, tells ThePrint, “Ladakh is in a state of limbo. No one is answerable to the people of Ladakh. Before this, at least the LAHDC had some powers. The government, instead of addressing real issues, has come up with policy patchworks, such as the Ladakh Industrial Land Allotment Policy, 2023, and Digitisation of Land Records in Ladakh. This firstly undermines the authority of the LAHDC, and raises concerns about accuracy, especially over community-owned land. The voice of Ladakh has been drowned.”

Hussain, resident of Thiksey village, reiterates the demand for half of the 7.5 percent reservation in central government jobs—over and above the 80 percent quota for Ladakhi Scheduled Tribes in UT government jobs.

“Ladakh competes under the general ST category for central government jobs. Most people here are first generation university passouts. We have been neglected for decades with limited opportunities, which makes it difficult for us to compete with STs from the mainland. The Meena community (primarily from Rajasthan and some from neighbouring states) takes a significant share of the ST quota in central government jobs,” the 38-year-old PhD scholar from Jawaharlal Nehru University says.

“The Dogras came and occupied Ladakh. It was a brutal repression…destroyed our economy and looted our monasteries. We need the Sixth Schedule and statehood to compete with other states, and so that Ladakhis who have been treated with such dismay can finally be liberated,” he adds.

According to Jayo of Stok village, while ST job quota looks amicable on paper, the ratio of jobs versus the unemployment rate, and the number of contenders, keep things in limbo. This alone cannot address the fears of Ladakhis, he says.

Jayo was formerly associated with the Congress party. “The frustration will keep building up till the time the inclusion in Sixth Schedule is not granted,” he adds.

Ladakh’s historical paradox: In conflict & unity

Ladakh’s Buddhist and Muslim communities, long divided by political, religious and cultural differences, came together over the past few years to fight for these demands due to the lingering fear of further marginalisation.

The National Commission for Scheduled Tribes (NCST) had written to the government in 2019, recommending the inclusion of Ladakh under Sixth Schedule. It had pointed out that “total tribal population in Ladakh region is more than 97 percent”, adding that Sixth Schedule would allow for “democratic devolution of powers”, besides preserving Ladakh’s “culture, protect land rights”, and “enhance transfer of funds for speedy development”.

The 97 percent figure includes not just the Buddhists of Leh, but also the Shia Muslim tribals of Kargil, such as the Baltis and Purigpas, among others. The Arghons of Leh, a Sunni Muslim community, are listed under the general category.

LAB member Ashraf Barcha, who represents Leh’s Shia community and is president of Anjuman Imamia Leh, says, “After abrogation of Article 370, J&K and Ladakh were bifurcated. Before 2019, we had some protection for our land, culture and other things. We had much more representation in the legislative assembly. After UT status, we have lost all of it. We wanted to be separate from J&K, and the idea was that the protection would be extended as well. Since then, people have been concerned about their future.”

He adds, “Now we just have one L-G, who controls everything, and a bunch of bureaucrats. We have no democratic say. One MP representing Leh and Kargil doesn’t suffice for 65,000 km. We are just three lakh in number, our identity will be wiped out. We demand statehood because we have seen in the last 6 years that without it, we won’t have any democratic say.”

For decades, Leh’s Buddhists and Kargil’s Shias have been at odds over identity, representation, resources, development priorities, and even polarised voting in elections.

Tensions had peaked when the two communities had clashed in Leh in 1989, prompting the Ladakh Buddhist Association—now part of LAB—to announce a boycott initially targeting Kashmiri Muslims and Ladakhi Sunnis, which was later extended to Balti Shias. This had coincided with the rise of Kashmir militancy, and the LBA had demanded UT status even then. The boycott had ended in 1992, and the Leh Autonomous Hill Council was established in 1995, partially fulfilling LBA’s demands.

The conflict had resurfaced in 2000, when then J&K chief minister Farooq Abdullah had sought to restore the erstwhile state’s pre-1953 autonomous status, prompting LBA to again push for UT status. Then too, Kargil and Leh shared a single parliamentary seat, with voting sharply communally polarised. The LBA had sought the prime minister’s intervention in inter-religious relationships, accusing Sunni Muslim men of Kargil’s Zanskar of luring Buddhist girls.

“This (the current movement) was the need of the hour, irrespective of caste, creed and religion. Everybody—Hindus, Muslims, Buddhists and Christians—feels deceived, and so we became one,” Barcha said.

The togetherness of both communities in conflict is also evident in their struggle for ST status for Ladakhi tribals. The All Ladakh Action Committee (ALAC) formed in 1980, comprising Buddhists and Muslims, had reignited the long-standing demand of the tribals, faced with decades of economic and educational disadvantages, compared to other regions of Jammu & Kashmir. Finally, in 1989, through the Constitution (Jammu and Kashmir) Scheduled Tribes Order, ST status was granted to the Balti, Beda, Bot, Brokpa, Changpa, Gara, Mon, and Purigpa tribes.

Despite the political and ideological differences—in some instances, they don’t even eat with each other due to their belief systems—Ladakh has a history of marriages between both communities. Even the uncle that Wangchuk had gone to stay with and study in Nubra Valley was a Muslim man.

A 35-year-old businessman in Leh said, “There have been differences between both communities and tensions rise when there is an inter-religious marriage, but for the greater good, the communities have now come together.” He, too, has Muslim relatives in his family, like many others.

This is an updated version of the report.

(Edited by Mannat Chugh)

Also Read: An ‘unbearably curious’ boy who became voice of Ladakh—a village recalls the story of Sonam Wangchuk

Government is WRONG in jailing Sonam Wangchuk. Keep the heat on Bismee! and The Print.