Barpeta/Guwahati (Assam): A year ago, he was a certified “foreigner” or, as they say in Assam, a “bidexi”, who was forced to lead a harrowing life in a detention centre. Today, Joynal Abedin has received the much-coveted stamp of being an “Indian citizen”, with the final list of the National Register of Citizens (NRC) not excluding him.

Abedin’s story, much like that of several others in the state who have been declared foreigners or “doubtful” citizens, exposes the glaring holes in the entire system of determining who is a legitimate Indian citizen and who isn’t.

It also shows how deep the faultlines run, and how the complex and ill-timed NRC process has only deepened them further.

The final list of the NRC, which aims at identifying those who immigrated illegally from Bangladesh after the cutoff date of 24 March 1971, was published on 31 August, leaving out around 19 lakh people.

The NRC may have kicked in only recently, after 2013, but this structure of labelling some people “foreigners” and sending them to detention centres is anything but new to Assam.

The state, with its long history of harbouring resentment towards outsiders, has six detention centres — at Goalpara, Silchar, Kokrajhar, Tezpur, Jorhat and Dibrugarh — all located inside prisons and meant to accommodate those identified as foreigners.

According to government data up to 31 January this year, presented in an affidavit to the Supreme Court, there are as many as 938 detainees lodged in these centres. These detainees live in traumatic circumstances, deprived even of basic human conditions.

Abedin was one such detainee, but today finds himself liberated.

He is one of the several purported “foreigners” interviewed by ThePrint earlier this year, all of whom painted a wretched picture of their situation.

In light of the NRC, we tracked down the interviewees to see where they and their families stand after the controversial exercise. While some said they stood vindicated, others found themselves grappling with new questions amid surprise omissions.

The paradox

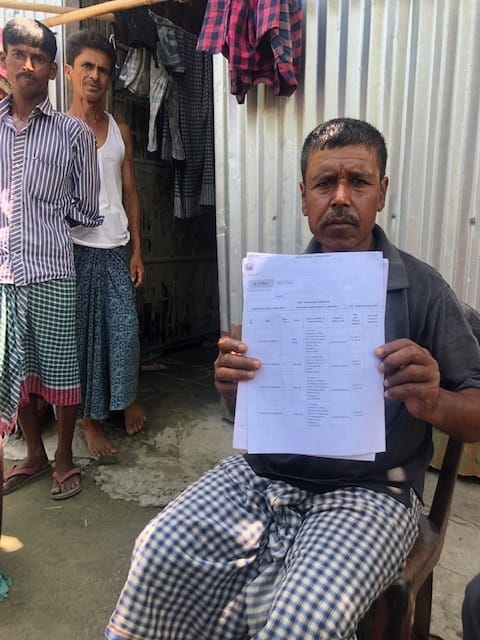

Abedin, a 55-year-old resident of Kathajhar Patha village in Barpeta district, was released from the detention centre at Goalpara on the order of the Gauhati High Court on 28 December last year.

But not before he had spent 14 months there, after he was declared a “foreigner” by a foreigners tribunal on account of unsatisfactory documents.

The irony, his name was there in the first NRC draft of December 2017. Despite being branded a foreigner and sent to a detention camp, his name hasn’t been excluded from the final NRC.

All but one of his four sons and three daughters have their names on the list — the one daughter left out is married.

Tragically for the family, Abedin’s wife Hazera Khatun, aged around 50, is not in the list either. The family of Abedin, a poor daily-wage labourer, had to give up much to fight his case earlier. Now, they are livid.

“I didn’t get a job for months after coming out of the detention centre. Now, I am forced to pull a rickshaw in Guwahati,” Abedin said.

“We are neck-deep in debt, my daughter’s studies had to be stopped. I have gone through so much trauma, nobody should have to go through that,” he added, “And all for what? NRC now has my name. This is what I have been saying all along — we are not foreigners.”

“It was mere suspicion that made the authorities doubt him. When my father was in the detention centre, we lived in so much fear,” said his son Habis Ali, 22. “For the first two months, we didn’t live at home, since we were so scared of being picked up and taken away. Now, we’ll have to go through the same cycle with my mother and we have no money at all.”

The family came to know of their NRC status after some young boys from the village looked it up on the internet. The family remains clueless about the current status of Abedin’s case, and believes it is “still before the high court and a local lawyer is taking care of it”.

They say the government “must compensate” them for what they went through.

Hazera Khatun, meanwhile, rues the fact that the joy of her husband’s release has proved short-lived. “I know what life in a detention camp is like. I feel very scared and don’t know what to do,” she said, “My name will finally appear (in the NRC), right?”

“My entire family went through misery,” added Abedin. “What I have managed to live through, nobody can.”

Also read: Assam’s NRC has created a needless crisis for India

The family conundrum

A fact many are struggling to come to terms with is how different members of a family can have different statuses.

Sofiya Khatun, 60, a resident of Bogorighuri village in Barpeta, reflects that confusion. She had to spend a year at one of Assam’s six detention camps before a Supreme Court order got her out on 12 September last year.

Khatun, who describes her stay in the detention centre as being “worse than hell”, hasn’t made it to the NRC. However, her husband has. Of her four children, one son and the couple’s lone daughter are in the NRC, while two sons aren’t.

This split of the family right through the middle has them confounded.

“My mother is a foreigner, my father is an Indian. My brother and sister are Indians, but my younger brother and I are not. How is that even possible,” asked Khatun’s son Saddam Hussain. He has filed for claims and gone for three hearings, none of which helped.

“I gave my father’s legacy documents, if he is in, so should I be,” he said. “Even if it is because of my mother that I haven’t made it to the NRC, then none of my siblings should have. This makes no sense. But obviously, this has made us feel scared.”

Khatun’s case is currently in the Supreme Court. She, however, can’t seem to wrap her head around why exactly she qualifies as a “foreigner”.

“I have five siblings. All of them have made it to the NRC,” she said. “How is it possible that I haven’t then? We have the same legacy.” ThePrint could not independently verify her claims.

In Silchar, Sulekha Das’ family finds itself in a similar position. The 60-year-old resident of Taligram in Silchar has been at the Kokrajhar detention camp since April last year, and her family continues to spend sleepless nights.

She hasn’t made it to the NRC. Of her three children — two sons and one daughter — only one son has made it to the final NRC list.

NRC officials claim they don’t look at families as a whole but at individuals, and “any discrepancy, error or technical mistakes in their papers can lead to such situations”.

‘Nobody is happy’

In Assam, those who have been identified as “D-Voters” or “doubtful voters” during electoral roll revisions are sent notices to appear before a Foreigners Tribunal before their fate is decided.

The first such exercise of identifying D-Voters was conducted in 1997, when 2,20,209 people were labelled thus.

Idris Ali, 46, of Barpeta is one of them. He says while he was declared a D-Voter in 1997, he was never sent a notice and, hence, did not pursue the matter legally. In the final NRC, he and his children haven’t made it, but he claims his brothers and mother have.

“I had thought the NRC may solve my problem, but it seems to have made it worse,” he told ThePrint. “Honestly, when I was first told about it, I did not even understand what a D-Voter was, so never took it seriously. Why will I be a foreigner if my mother and brothers aren’t? Now we really don’t know what to do.”

Ali’s wife Shahtun, 39, is on the list as well. Married women are required to give the legacy documents of their fathers and grandfathers and not of their husbands, which is why this discrepancy isn’t rare. But Shahtun says she has little to feel pleased about.

“My name may have appeared, but I am anything but happy. How can I be, when my children and husband have been left out? What kind of a country is this that tells a mother that you are ours, but your children and husband aren’t?”

Also read: Assam agitation hotbed shows why NRC is nothing but a National Recipe for Chaos