Srinagar: Four-feet tall in his boots, his walk marked by a limp, Noor Muhammad Tantray was carried to his grave in the village of Aripal, in southern Kashmir’s Tral, by a crowd of thousands, shouting anti-India slogans and throwing stones at police. Long a key figure in the local Jaish-e-Muhammad and lieutenant to Parliament House attack organiser Rana Tahir Nadeem, also known as Ghazi Baba, Tantray had been arrested, served five years in jail, and then, after being paroled, resumed terrorist attacks before being killed in 2017.

Earlier that year, Zakir Bhat—the founder of the Ansar Ghazwat-ul-Hind, al-Qaeda’s Kashmir affiliate—had threatened to chop off the heads of leaders who opposed the imposition of the Shari’a.

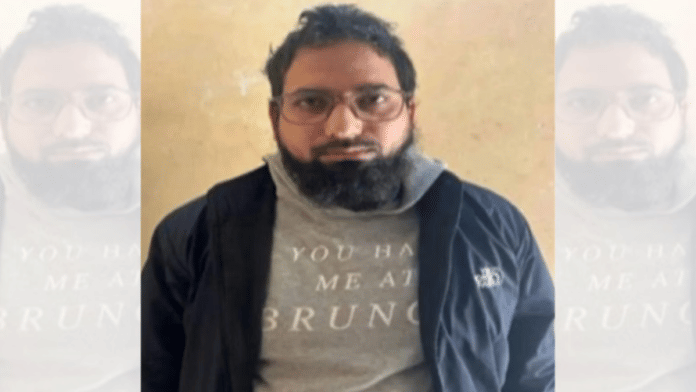

Twenty-three at the time, Irfan Ahmad Wagay—the Sringar cleric at the centre of the circle of doctors now alleged to have plotted massive bombings and attacks in New Delhi—was certain the Kashmir jihad was headed for victory, police sources familiar with his case have told ThePrint. Wagay helped courier weapons and maintain caches for a group of Ansar Ghazwat-ul-Hind terrorists.

Less than two years later, India ended Kashmir’s special constitutional status and flooded the region with troops. The India-Pakistan crisis of 2019 led Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence Directorate to curtail the Jaish-e-Muhammad’s operations under mounting international pressure. The Ansar Ghazwat-ul-Hind, lacking an external sponsor, was decimated by 2021.

Wagay—with no formal education past the sixth grade, no qualifications as a cleric, and no training in combat or intelligence tradecraft—crafted a plan to keep Kashmir’s jihadist movement alive.

Also Read: Kashmir’s new-generation jihadis want to attack India’s heartland, not just its army

The cleric’s war

Wagay was an unlikely ideologue—all the more so for a group that was to be largely made up of highly-qualified medical professionals. For one year in 2007, Wagay joined the Dar-ul-Uloom Bilalila, the largest seminary in Kashmir that is patterned on the curriculum and practices of the famous Dar-ul-Uloom seminary in Deoband. Founded in 1991, and located on the banks of the Nigeen lake, the seminary offers residential accommodation for over 550 students, mainly from economically underprivileged backgrounds.

Then, he moved back to his hometown Shopian, spending a year and a half receiving an education at a seminary at Pinjora in southern Kashmir. His classmates there included Muzammil Tantray, who would later join Kashmir’s al-Qaeda wing. Shortly before his death, Tantray is believed to have handed the weapons later acquired by the Doctors’ Cell to Wagay.

Like other Deobandi institutions, the Dar-ul-Uloom Bilalia straddled one of the most important religious faultlines in South Asia. Founded in the wake of the failed Thana Bhawan revolt against the British, Deoband had been set up in 1866 to create a vanguard for Islamic religious revival.

Following independence, the movement diverged in India, Pakistan and Afghanistan—spawning organisations like the Jaish-e-Muhammad and the Taliban, but also a stolid pietism that largely stood aside from politics. Even though the Dar-ul-Uloom supported Kashmir’s accession to India and the secular State, students and some faculty supported the deeply reactionary positions that had flowered in Pakistan.

After the Gujarat communal massacre of 2002, some students at the eminent Dar-ul-Uloom Islamia Arabiyya seminary in Bharuch supported the Lashkar. Sana-ul-Haq, a one-time seminarian at the Dar-ul-Uloom Deoband, joined the Harkat-ul-Mujahideen in Pakistan, going on to become the founding leader of Al-Qaeda’s South Asia wing.

Lacking the formal credentials to become a cleric, Wagay began making a living giving religious lectures at a small mosque in Nowgam, a Srinagar suburb. Though media have reported he worked as a paramedic, records at the Government Medical College in Srinagar show he never applied for nor held such a position. Instead, he appears to have made contact with key cell members Adil Ahmed Rather and other doctors through his study group.

Through long discussions, conducted in person and over online chat rooms, the group became persuaded that a jihad of attrition was pointless. As first reported in ThePrint, they sought out opportunities to train in Afghanistan to carry out a 26/11-style mass attack in Delhi. Failing in that effort, they set about learning to make bombs and use weapons online.

Even though Wagay made some effort to keep jihadist sentiments alive in Nowgam—notably by asking his supporters to put up Jaish-e-Muhammad-branded posters on nearby walls—he increasingly focussed on the doctors’ plans to stage a mass-casualty strike.

Almost certainly, his decision was driven by the complete failure of the jihadist movement in Wagay’s south Kashmir homeland after 2019, as the handful of recruits who trickled into jihadist groups were eliminated.

Last men standing

Late on a December morning in 2023, Zakir Ahmad Ganie began to die of a broken heart: the parents of the woman he loved, Nadia Jan Parray, declined his proposal of marriage for the third time. Furious, the 27-year-old metalworker, who had dropped out of the Government High School in Ashmuji in his ninth grade, turned to his friends. They promised him a new life, with dignity and purpose, a police officer familiar with the case said, “Ganie would now be a jihadist of the Lashkar-e-Taiba, operating around the villages of Khudwani and Redwani in Kulgam.”

Today, he’s just one of three men alive of the 16 ethnic Kashmiri jihadists known to have been active in 2019. Among them is Firdaus Ahmad Bhat, a one-time autorickshaw driver who left for Pakistan on a family-visit visa in 2017, and is since believed by Indian intelligence to work for the Lashkar. The third survivor, Haroon Rashid Ganie, left for Pakistan in 2018, after a fight with his wife, travelling on legitimate documents.

The annihilation of cadre recruited since then, though, has convinced jihadists—including the members of the so-called Doctors’ Cell—that warfare within Kashmir was a losing game.

Kulgam resident Zahid Dar worked as a salesman at a local market after dropping out of middle school. In 2019, he was sentenced to detention under the controversial Public Safety Act, which allows for imprisonment without trial. The teenager’s family, though, won his release through the courts. For some months, Zahid ran a clothes store in Yaripora before leaving home to join the Hizb-ul-Mujahideen.

Few of the new recruits, like the members of the Doctors’ Cell, had a religious education. Yawer Bashir Dar, born in south Kashmir in 1993, and reported to have been killed last year in the course of an ambush targeting a military search party, had planned to join the Madrasah Idarah Tehreek Sawt-ul-Awaliya. The Covid lockdown intervened, though, and Dar lost interest in the idea, the police officer said.

Like the followers of Irfan Ahmad Wagay—the cleric who inspired the Doctors’ Cell planning strikes in New Delhi—the new terrorists spent much of their time occupied in propaganda work. Lashkar operative Aqib Shergojri, government records show, handed out posters to a small group of lieutenants. Educated briefly at a Deoband-affiliated seminary after he dropped out of high school in 2021, he then worked as a car mechanic for a year.

Then, last year, Shergojri was killed in an exchange of fire with Indian forces at the village of Adigam.

Among the recruits were several from backgrounds of extreme poverty. Zahid Ahmed Reshi, born in Shopian’s Arwani village in 1993, dropped out of school after eight years of education to support his family. He worked as a labourer and at a store selling chicken before leaving home to join the Lashkar-e-Taiba front organisation, The Resistance Front.

Zahid, police believe, involved himself in killing migrant workers in Kashmir, part of an initiative to undermine the post-2019 order. Following a few months of participation in these execution-style killings, Reshi was hunted down by Indian forces and shot dead.

(Edited by Ajeet Tiwari)

Also Read: War was the norm between Afghanistan and Pakistan. Asim Munir is bringing it back