Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party has a cash stockpile of nearly $1.3 billion while its main rival has just 6.6% of that amount, giving India’s ruling party a strong advantage ahead of key state elections.

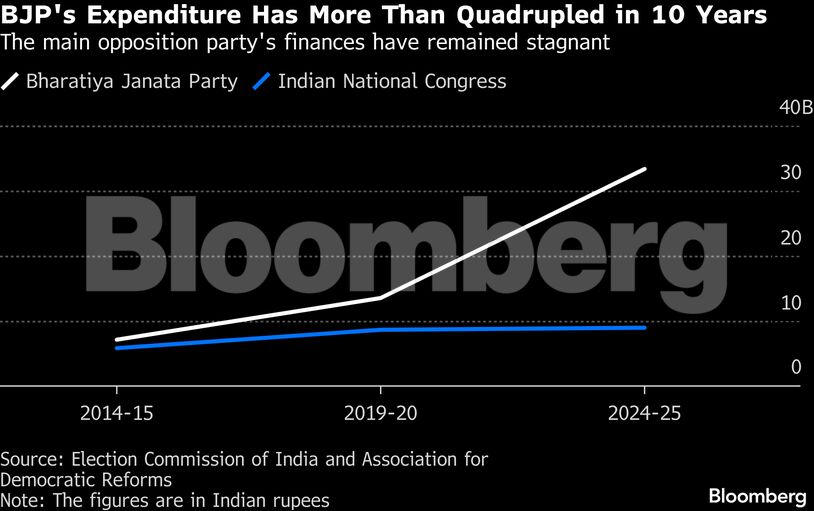

The BJP spent 33.35 billion rupees ($364 million) between 2024 and 2025 on election-related expenses, about 65% of which went into advertising across television, print and digital platforms, according to audit reports released by the Election Commission of India this week. The spending was nearly four times higher than the amount spent by its primary challenger, the Indian National Congress, during the same period.

That financial firepower puts the BJP at a significant advantage in five state elections due in the coming months, including opposition strongholds such as Tamil Nadu and West Bengal. The funding gap has weakened Congress and smaller regional parties, reinforcing the BJP’s dominance even outside its traditional bases.

The audits based on disclosures up to March 2025 understate the full extent of political spending in India, as much of party financing takes place off the books. Yet the latest figures released by the Election Commission show a 1,466% jump from the $83 million in reserves the BJP reported in 2015, a year after Modi began his first term, to the $1.3 billion it amassed within a decade.

With its war chest expanding, the BJP reported campaign expenditure of 13.52 billion rupees ($147 million) covering the 2019 national election, while the Congress party had spent 8.64 billion rupees ($94.2 million).

In upcoming state polls, the BJP’s vast funding advantage will “act as an entry barrier to independent candidates who may not have wealth and to smaller parties who would like to contest elections, because there would not be an equal playing field,” said Shelly Mahajan, Program and Research Manager at the New Delhi-based Association for Democratic Reforms. “Donations are going to a single party and disproportionately,” Mahajan added.

India’s parliamentary polls, the world’s largest electoral exercise, involves nearly a billion registered voters. Political parties buy advertising across newspapers, television, and radio and pour money into social media to reach voters digitally. Party heavyweights arrive in key voting districts on chartered planes and helicopters, stage long motorcades and rallies where crowds are treated to sweets and snacks, making the election season a cash-intensive enterprise.

For N. Bhaskara Rao, chairman of the New Delhi-based Centre for Media Studies, the BJP’s financial edge is “unparalleled in the annals of Indian democracy,” as the size of its wealth suggests the party wants to cement its lead for “decades to come”.

Unaccounted cash flows ahead of polls and weak enforcement have complicated efforts to police election spending. According to Rao, only “one-third or one-fourth” of the total amount spent by a political party is legally declared to the authorities.

Federal authorities seized billions of dollars in illicit money, drugs and other goods in election-related raids in 2024. The contraband was meant to lure voters at a large scale.

The same year India’s top court banned anonymous political funding through “electoral bonds,” a system introduced by the BJP-led government in 2017 that allowed every party to raise funds behind closed doors. The BJP benefited the most from the opaque scheme, drawing money from donors ranging from small businesses to large conglomerates. Declaring the practice unconstitutional and a violation of the right to information, the court ruling was intended to narrow imbalances in campaign resources. Two years on, it has yet to level the playing field.

The BJP’s consistently wide winning margins have often prompted allegations of voter fraud from the opposition — a charge the ruling party denies. On the ground, the prevailing perception is that financial muscle, combined with Modi’s popularity and appeal to religious nationalism, gives the party an air of invincibility.

“Political parties need to come together and they need to debate reforms,” said Mahajan. “There’s no dearth of recommendations from the law commission or previous election commissioners but it’s just that there needs to be political will.”

This report is auto-generated from Bloomberg news service. ThePrint holds no responsibility for its content.