Raipur: For 15 months, Pooja Sharma lived the life she had worked so hard for. Five years of studying, entrance exams, and interviews had finally landed her a government teaching job. She moved deep into Bastar’s forests to teach primary school children and earned her own money. Then in December, the Chhattisgarh government sent a termination order.

She and nearly 3,000 other teachers were out. They were too qualified for their jobs.

Since 14 December, she has been protesting in Raipur, travelling 8 km every day to join demonstrations along with over 2,000 others. After 38 days, the protests paused due to municipal elections, so they have now switched to a digital campaign—tweets, videos, posters, anything to be heard.

“It wasn’t just a job for me. It was my identity, my gateway to independence and freedom. They took it all away in one go,” said Sharma, sitting with 15 other teachers during their weekly meeting at a park in front of the Nagar Nigam building in Raipur. “I am protesting here, taking care of my child, and managing my household. Financial independence is very important to me.”

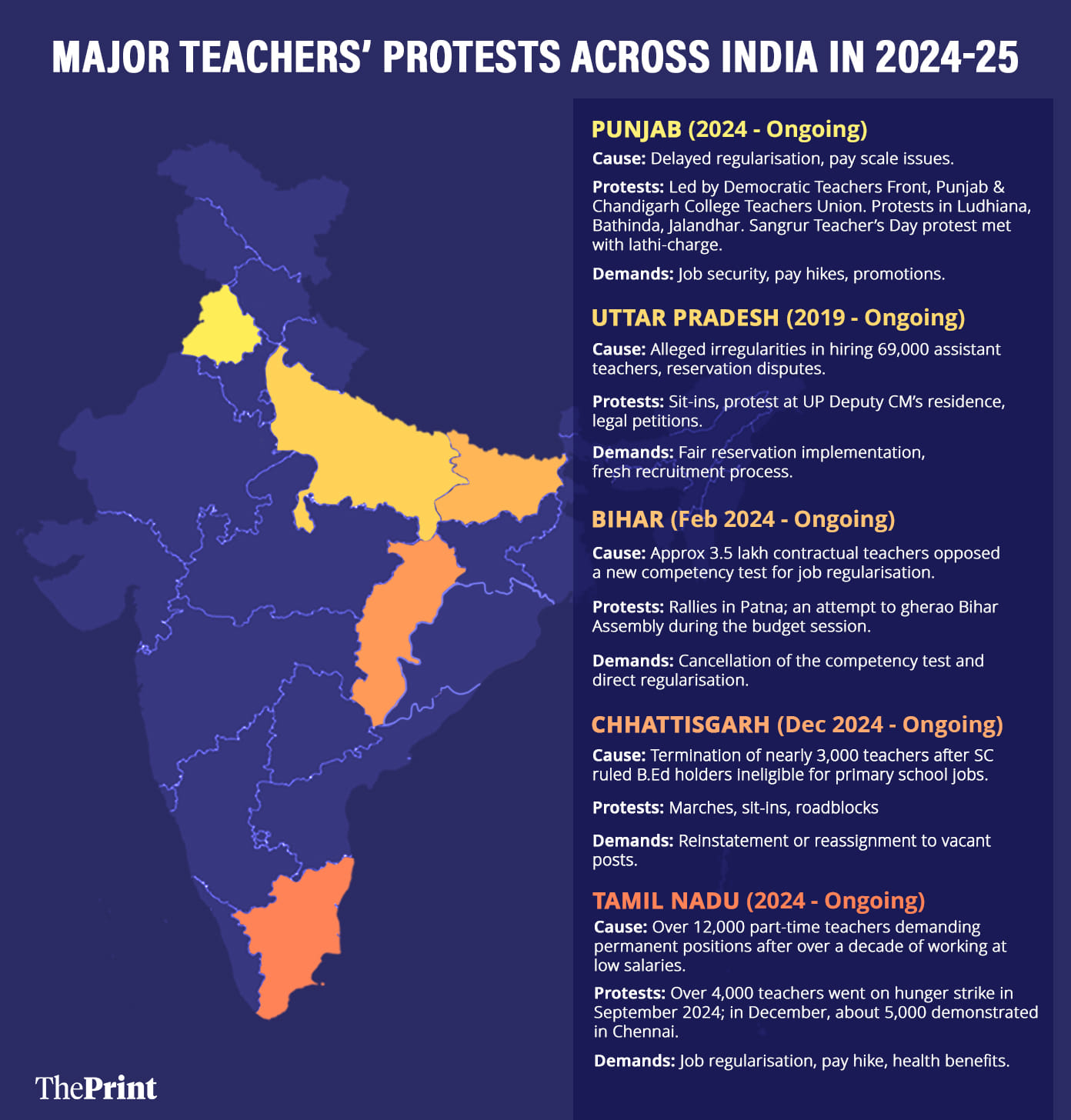

But Chhattisgarh’s teachers aren’t alone in their fight. There is a brewing teacher crisis across India. It isn’t the shortage of teachers or teaching jobs. School teachers are caught in a web of recruitment scandals, new competency examinations, ad-hocism, and low salaries. In some places, they are fighting for their appointments; in others, they are demanding better pay, improved working conditions, and permanent postings.

For years, teaching was a middle-class aspiration. It was viewed as a safe job with fixed work hours and months of summer holidays. A government teaching job also meant social mobility and respect for lower middle-class youth. But now, teachers are on the street, dodging police batons, shouting slogans, burning effigies, tonsuring their hair, and even holding begging bowls to prove their point.

Many such protests have erupted over the last several months. In Jharkhand, police fired tear gas at teachers demonstrating for a pay raise. In Punjab’s Sangrur, unemployed teachers marching toward the Chief Minister’s residence were lathi-charged. In Chennai, 5,000 teachers protesting for job regularisation clashed with police. In Bihar, over 3.5 lakh teachers rose in protest against a new competency test, even attempting to gherao the Bihar Assembly during the budget session.

In Chhattisgarh, a legal and bureaucratic tangle led to this situation, leaving many students without teachers.

In May 2023, the Chhattisgarh government announced primary teacher vacancies and allowed Bachelor of Education (B.Ed) degree holders to apply. Exams were conducted, a merit list was released, and jobs were filled. But in August, the Supreme Court ruled that primary teachers needed a D.El.Ed, not a B.Ed. This led to a court challenge by D.El.Ed holders, and the Chhattisgarh High Court ruled in their favour, a decision upheld by the Supreme Court.

In the first week of December, the High Court gave the government six weeks to revise the selection list, leading to the abrupt termination of 2,896 teachers.

Government officials say a committee has been formed to address the matter.

“Per the high court’s order, a decision was taken to appoint qualified D.El.Ed assistant teachers in place of B.Ed teachers. The state government had gone for an appeal and review in the SC. Now it has formed a committee under the chairmanship of the chief secretary to look into the issue,” said Siddhartha Komal Pardeshi, Chhattisgarh’s secretary of education.

Sharma is still struggling to make sense of it all and blames the government for turning her life upside down.

“When I saw the notification, it said B.Ed teachers were eligible. If I had known this, I wouldn’t have wasted years preparing for an exam that wasn’t even meant for me,” she said, her eyes welling up. “It’s the system and the government’s fault, but we are paying the price with our time and future.”

In tribal districts like Bastar and Surguja—where most of the B.Ed teachers were recruited and then dismissed—government schools already struggle with staff shortages. Now, indefinite vacancies leave children without teachers.

Also Read: India’s coaching institutes are having a meltdown. Teachers, students dropping out

Fired over ‘wrong’ degree

On 10 June 2023, Pooja Sharma left home early in the morning for her teacher recruitment exam in Raipur. A month later, her name was on the merit list. In September, she had an appointment letter—but it came with a warning.

“The joining letter said that this matter is in court and the future will be dependent on the decision that will come. We always thought the government would fight in the best way possible, but that didn’t happen,” Sharma said.

When the termination orders came in December 2024, protests erupted. Teachers blocked roads, burned effigies, shaved their heads. In January, 30 were arrested during a dharna outside the ruling BJP’s headquarters in Raipur.

With urban and panchayat elections approaching, the model code of conduct kicked in on 11 February, forcing them to cease street protests. While the restriction has now lifted in cities, rural areas remain under limits until 23 February. For now, teachers are making their voices heard online.

“I had never used Twitter (X) before this but now I have made my account and post every day multiple times. We cannot protest physically due to the achar sanhita but we will do whatever we can to reach out to the government,” said Kiran, 29, who got her termination letter a week before her wedding.

We are saddened by this but if we will give them other postings then some other people will go to court as they will be hired without the process

-Chhattisgarh government official

One of her posts, written in Hindi said: “Look at the plight of women in Chhattisgarh. Their only ‘crime’ is that they succeeded on merit. Had they focused on household chores instead of studying, they might have been spared this ordeal.”

For the dismissed teachers, giving up isn’t an option. Many had quit private jobs, moved away from their families, or even had marriage engagements broken after losing their government salaries. Protesters claim many of those dismissed were Scheduled Tribe women.

“There are people who literally have majdoor cards—women who used to do labour in the day and study in the night for this. What will they all do?” asked Ankit Chaubey, who left a high-paying private school job for government service.

Chaubey, a protest leader, says the ordeal began with conflicting policies over the years.

In 2018, the National Council for Teacher Education (NCTE) allowed B.Ed holders to be appointed for primary school teaching jobs. States such as Chhattisgarh updated their recruitment rules accordingly.

“However, in 2021, a controversy erupted when Rajasthan excluded B.Ed holders from its Teacher Eligibility Test, prompting legal battles between B.Ed and D.El.Ed candidates,” said Chaubey, speaking as if reciting an essay.

The case reached the Supreme Court, which ruled in August 2023 that only D.El.Ed-trained teachers were eligible for primary schools. The court noted that a B.Ed degree was meant for secondary and higher secondary education.

“The court protected those who were appointed before its judgment but people like those who joined in September became uncertain. The lawyers appointed by the government in the case didn’t represent us—otherwise our jobs would be safe too,” said Chaubey.

After the ruling, the Chhattisgarh High Court halted B.Ed teacher appointments in September 2023. Yet, just weeks before state elections, the Congress government issued appointment letters anyway. The party lost to the BJP in December.

Last April, the Chhattisgarh High Court ruled against these appointments, a decision upheld by the Supreme Court in August. Then in December, the High Court gave the government two weeks to revise the selection list, warning of serious consequences for non-compliance.

“Around 3,000 teachers are jobless just because of the administrative failure. Now we want the government to put us in different vacancies. There are thousands of teacher posts vacant in the state,” said Chaubey.

But the government isn’t budging. Officials say reassigning the teachers to other vacant posts could lead to fresh legal challenges.

“We are saddened by this but if we will give them other postings then some other people will go to court as they will be hired without the process,” said a senior government official, speaking on condition of anonymity. “We can’t go against the Supreme Court’s verdict. We posted the best lawyer in the case. It is very bad for the teachers but we can’t do anything about it.”

Another issue that has triggered protests in different states is the spectre of competency tests for employed teachers, with many fearing they could lose their jobs despite years in service.

‘UP’s Vyapam’

A long-awaited recruitment drive for 69,000 assistant teachers in Uttar Pradesh was meant to provide stable government jobs. Instead, it triggered six years of protests. First came allegations of paper leaks in the 2019 exam. Then, after results were declared, an outcry over an alleged reservation scam.

Teachers have marched, gone on hunger strikes, and braved lathi charges. They have camped outside government offices, staged demonstrations at the deputy chief minister’s residence, and taken their fight to the courts.

They claim that out of 18,500 seats reserved for Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, and OBCs, only 2,637 were actually allocated correctly, while the rest allegedly went to general category candidates.

This is just the latest in a long string of fraud allegations and court battles in Uttar Pradesh’s teacher recruitment. More than once, there’ve been comparisons to Madhya Pradesh’s Vyapam scam, one of India’s biggest government job scandals. If a 2022 paper leak in the UP Teacher Eligibility Test was dubbed Chhota Vyapam, this one has been called UP’s Vyapam by opposition leaders like Priyanka Gandhi.

If the system hadn’t failed us, I could have been a primary teacher earning Rs 52,000 a month. Instead, the most crucial years of my youth are being spent in protests and legal battles

-Amrendra Patel, UP teachers’ protest leader

The Yogi Adityanath government initially promised relief to protesting candidates but has since dismissed them as “pawns” of the Samajwadi Party.

Among them is 32-year-old Amrendra Patel, an OBC candidate who applied for a teaching job under the 69,000-teacher recruitment drive. He and other protesters allege that many reserved-category candidates had not received their rightful quota.

“It was so unfair to us. A government-appointed review committee confirmed discrepancies in implementing the reservation policy. We are walking in circles with the government and courts. This job is a big hope for my family’s survival,” said Patel.

His family lives in Prayagraj but he has been protesting in Lucknow for the last five years. He completed an LLB degree in this time but remains unemployed and relies on crowdfunding to sustain himself.

Lucknow’s Eco Garden has been the hub of these protests, with numbers swelling whenever there’s a new court ruling. Some 250 teachers sat on dharna here last August, but now around 10 remain as they await a Supreme Court verdict.

They have taken their case to every possible authority—the National Commission for Backward Classes (NCBC), the National Commission for Scheduled Castes, and the state government. Petitions from both general and reserved category aspirants have also been filed in the Allahabad High Court.

“The NCBC has acknowledged that there were issues in implementing the quota in the exam. The court also ruled in our favour, but delays in implementing the order are playing with our futures,” said Patel.

There is still no resolution in sight.

In 2021, Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath promised a “swift and fair solution”, including a corrective recruitment drive. But instead, 6,800 additional candidates were selected—only for the process to be halted when UP Assembly elections were announced.

The courts stepped in as well. In January 2022, the Allahabad High Court stayed the recruitment of these 6,800 candidates, questioning how the government could appoint them when all 69,000 posts had already been filled.

Last August, after hearing 91 petitions, the Allahabad High Court ruled that the government must scrap the old selection list and prepare a fresh one within three months.

That verdict was challenged in the Supreme Court by general category appointees. On 9 September 2024, an SC bench led by then Chief Justice DY Chandrachud stayed the High Court’s order. The matter was scheduled for 18 February but was postponed with no new date announced yet.

Meanwhile, in the UP Assembly last December, the government defended its handling of the issue.

“Out of the 34,500 posts reserved for the general category, only 20,000 candidates were recruited. These facts should serve as an eye-opener for those who attempt to create divisions in society for political gain,” Adityanath said.

But protesters like Patel aren’t backing down. They demand that the UP government advocate for reserved category candidates in the Supreme Court and ensure the NCBC and High Court orders are implemented.

“If the system hadn’t failed us, I could have been a primary teacher earning Rs 52,000 a month. Instead, the most crucial years of my youth are being spent in protests and legal battles,” said Patel.

Getting the job isn’t enough

Securing a government job doesn’t mean stability. Across India, teachers are fighting for promotions, permanent positions, better pay, and pensions.

In Tamil Nadu, teachers have been mobilising over multiple issues for the past year. Over 12,000 part-time teachers have been demanding permanent jobs after more than a decade of low wages. In December 2024, around 5,000 teachers protested in Chennai, calling out the DMK government’s unfulfilled promise of regularisation.

Pensions are another flashpoint. In January 2024, over 50,000 members of the Joint Action Council of Teachers Organisations and Government Employees Organisation (JACTO-GEO) took to the streets across the state. Their demands: restore the old pension scheme (OPS), fill 3.5 lakh government vacancies, and reinstate earned leave benefits, which were suspended in 2020.

“Our primary demand is the restoration of the OPS, as over 20,000 staff members who retired under the contributory pension scheme have not received monetary benefits or pensions,” said Chennai-based Rajasekar, district secretary of the Tamil Nadu Teacher’s Federation, a part of JACTO-GEO. “The Tamil Nadu government has also stopped earning leave benefits for teachers and employees since 2021, and we want them reinstated.”

While Tamil Nadu Finance Minister Thangam Thenarasu said last year that these demands would be “considered” by the government, teachers say nothing has changed. JACTO-GEO has now announced a statewide protest on February 25.

We have been doing the work of teaching and learning for the last 20 years. Now, the government is asking us to prove our ability. If we were not qualified, why were we allowed to teach children for so many years?

-Mrityunjay Thakur, a Bihar teacher protesting against the competency test

Further north, Punjab has also become a hotspot of teachers’ protests over grievances such as job insecurity, pay cuts, and government inaction. Such has been the disruption that in December 2024, Punjab education secretary Kamal Kishore reportedly tried to curb demonstrations by issuing a “no work, no pay” order.

But the protests have continued into 2025. Teachers in Ludhiana, Bathinda, and Jalandhar have been demanding job regularisation, including by burning effigies of state officials. Many of these highly qualified teachers—including PhD holders and NET-qualified professionals—have been working on temporary contracts for over a decade despite clearing all required exams.

On 30 December, Punjab teachers even landed in Delhi and were detained by police when a contingent tried to gherao Aam Aadmi Party national convenor Arvind Kejriwal’s house. They were protesting the Punjab AAP government’s implementation of the 7th Pay Commission, which, instead of benefiting them, allegedly left many at a financial loss.

“In 2016, 4,500 teachers were appointed as regular teachers. And after 180 teachers were put under the 7th Pay Commission, their salaries were slashed by half. The probation period was also extended to eight years, and the government nullified the probation that teachers had already completed,” said one teacher who protested in front of Kejriwal’s residence.

Another issue that has triggered protests in different states is the spectre of competency tests for employed teachers, with many fearing they could lose their jobs despite years in service.

In Bihar, over three lakh teachers recruited under a 21-year-old government scheme are fighting against a requalification exam they must clear to be regularised. Similar unrest was seen in Tamil Nadu’s Erode where government teachers resisted new evaluation criteria, and in Uttarakhand’s Dehradun, where teachers feared mass terminations due to stricter competency requirements.

“We have been doing the work of teaching and learning for the last 20 years. Now, the government is asking us to prove our ability,” Mrityunjay Thakur, a Bihar teacher protesting against the competency test told ThePrint last February. “If we were not qualified, why were we allowed to teach children for so many years?”

Also Read: Govt jobs are changing. PSU bank staff live in pressure cooker, 9-5 replaced by 24×7

Collateral damage

The protests never truly end. From Punjab to Uttar Pradesh, Chhattisgarh to Bihar, teachers fight for years, risking their jobs and pausing their lives, only to start over again. Even victory—securing pay hikes or job regularisation—can be tenuous. And then they are back on the streets, demanding what was promised but never fully delivered.

Pooja Sharma is filled with grim determination. As soon as the model code of conduct lifts, the teachers will resume protests full force.

Her salary—Rs 38,000 a month—is gone. Her future is blurry.

“I am back to zero, I will have to ask my husband for money,” she said. “But this is not the end. I will fight for what is mine.”

But students also pay the price. Various international studies have shown that teacher strikes can negatively impact student performance as well as long-term earnings.

In tribal districts like Bastar and Surguja—where most of the B.Ed teachers were recruited and then dismissed—government schools already struggle with staff shortages. Now, indefinite vacancies leave children without teachers.

There is no replacement yet for Pooja Sharma at her Bastar school, where she taught Class 5 students. The children were heartbroken when she left. She still gets calls from them, but every conversation ends the same way—she cannot come back.

Now, those lower on the merit list will eventually fill vacancies.

“My students are waiting for a teacher and now they will hire those who did not score as much as me,” Sharma said. “Those students will get a less competent teacher.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)