New Delhi: Rohtash Singh, a farmer in Haryana’s Sangwan village, is one of the few in his village who has a digital identification number for his land.

For Singh, the Bhu-Aadhaar—or Unique Land Parcel Identification Number (ULPIN)—has been a game-changer. He says it has made accessing government schemes and bank loans much easier by cutting through the red tape that slowed down the process earlier.

“Today, land record details are needed to access government schemes such as Kisan Credit Cards. Earlier, it used to take us months to get a copy of our land records,” the 45-year-old Singh, who owns over two acres of land, told ThePrint.

“But today, the information is available online and we can get a certified copy from the district office in a few days. Banks also don’t take much time to sanction loan requests against our property.”

Singh is among lakhs of people in villages across India reaping the benefits of the Bhu-Aadhaar scheme which assigns a unique 14-digit alphanumeric code to every land parcel based on its geographical coordinates.

This digital identification is linked to landowners’ bank records to streamline access to financial services and government benefits.

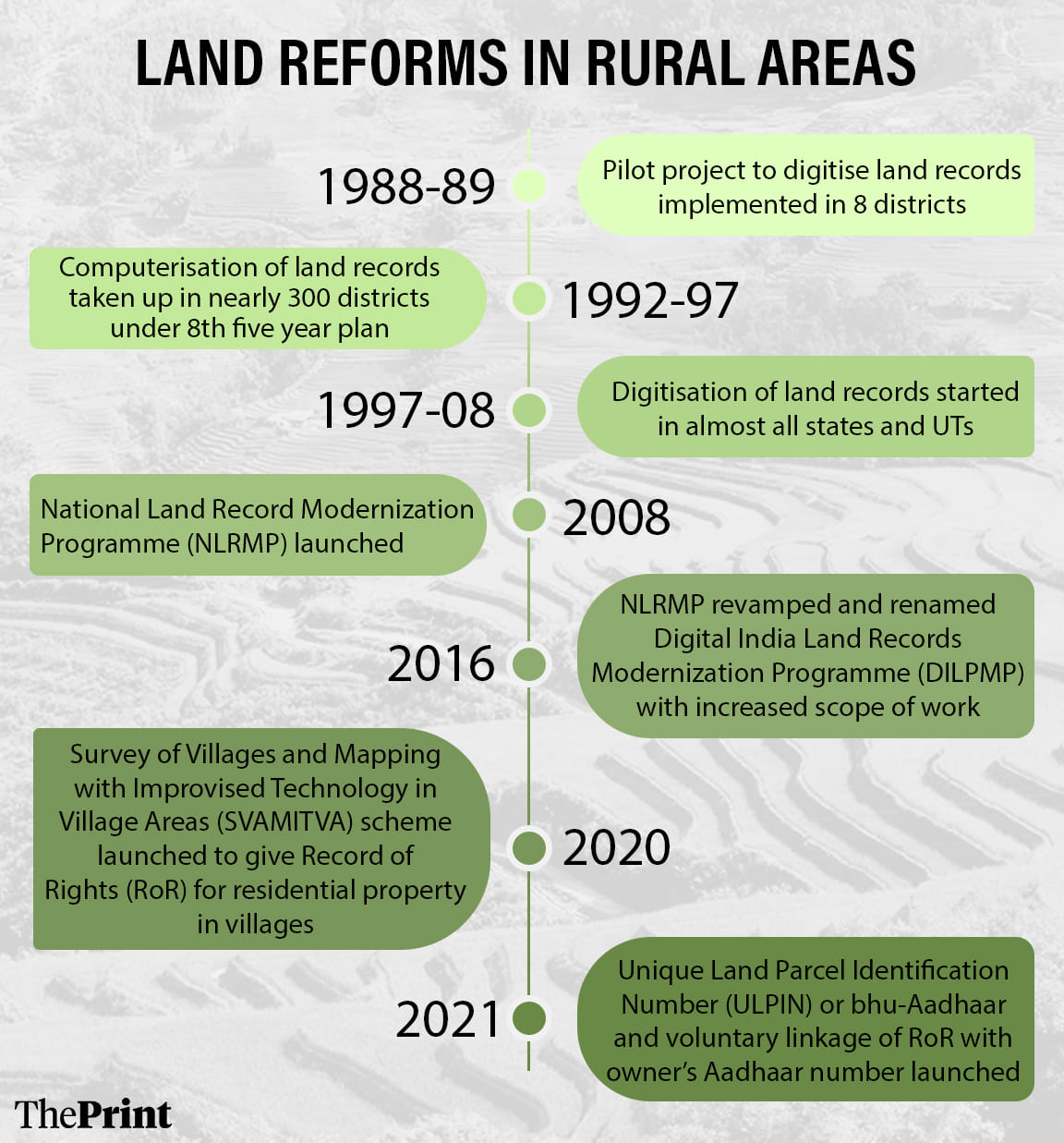

Launched in 2021, the ULPIN scheme is among the slew of technology-driven land reform initiatives implemented under the Centre’s broader Digital India Land Records Modernization Programme (DILRMP) that aims to digitise the country’s complex agricultural land records and bring transparency to land transactions.

An amount of Rs 2,428 crore has been released to states and Union territories between 2008-09 and 2024-25 for the programme, the rural development ministry said in a press statement.

The programme’s scope is staggering.

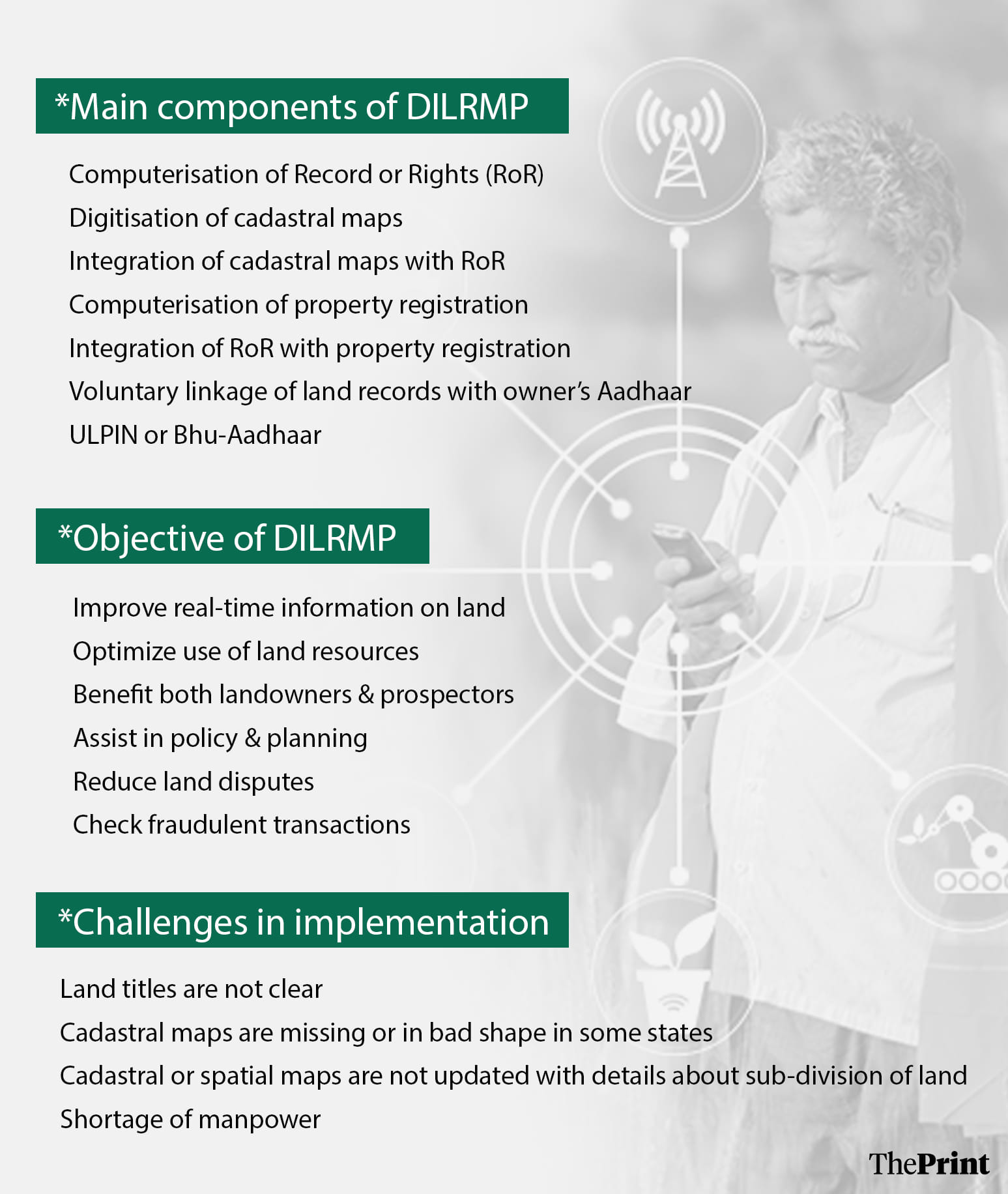

It doesn’t just involve digitising land records and providing a unique ID for each land parcel, it also includes integration of land records with revenue and civil courts, digitising cadastral maps which pinpoint the precise location of each land parcel, integrating land records with cadastral maps, computerising property registration and linking it to land records, and linking land records with Aadhaar.

In 2008, the then-UPA government launched the National Land Records Modernization Programme (NLRMP), which was renamed DILRMP in 2016.

It is among the most challenging reforms the Centre is implementing in coordination with state governments to bring transparency in land records, prevent land fraud and help states generate revenue through stamp duty and property tax.

More than 15 years after the Central government kicked off the ambitious land reform programme, it has made significant headway but the progress has been uneven because of its sheer scale and complexity.

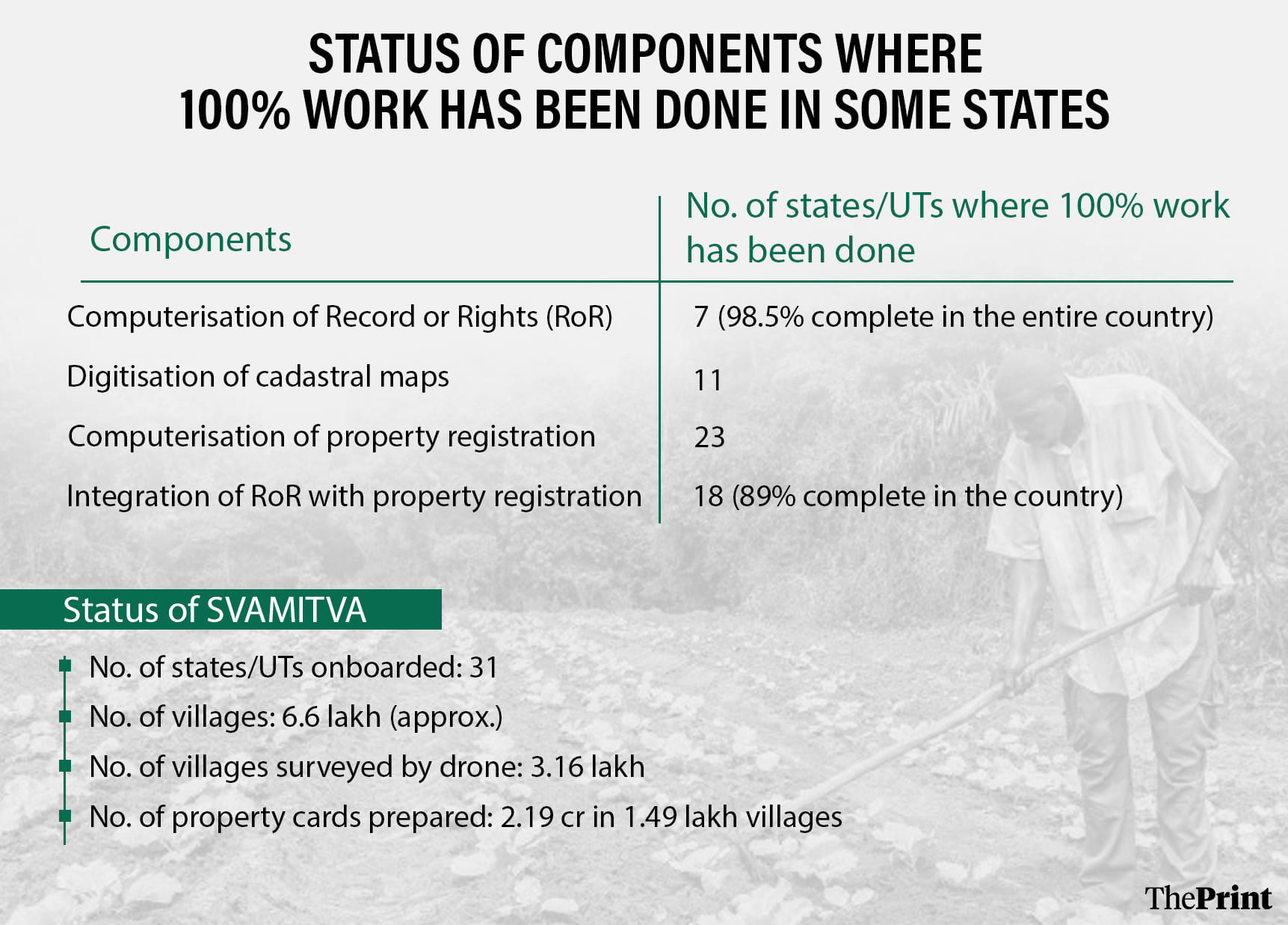

According to information provided by the Union rural development ministry in the Lok Sabha, 98.5 percent of land records, or Record of Rights (RoR)—have been digitised, with seven states completing the entire process and the rest nearing completion. Land records of over 6.47 lakh out of a total of 6.57 lakh villages in the country have been digitised so far.

Additionally, the integration of revenue and registration records has been completed in 89 percent of sub-registration offices in the country, according to a ministry statement.

However, with just a little over a year left for the initiative to conclude by 2026, a lot of work remains pending across several components.

For instance, only 11 states and Union territories have wrapped up the digitisation of cadastral maps, a critical step in the process, so far and the government had given ULPIN numbers with land geo-coordinates to just a little over 30 percent of land parcels, or 8.4 crore, till October this year.

While many states and UTs are rushing against time to wrap up all the elements of the programme before a March 2026 deadline, some have begun rolling out a few digital land-related services to increase transparency in land transactions. They include providing data about bank loans and pending court cases related to land parcels.

Last year, the Uttar Pradesh government, for instance, started providing information about bank loans taken against land in rural areas by property owners on its land records portal, UP Bhulekh, said a senior official with the state government’s revenue department.

Similarly, states like Karnataka, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra are also providing crucial land-related information online as their land record digitisation process is nearly complete.

A senior revenue department official in Uttar Pradesh told ThePrint the idea is to provide a one-stop facility for all land-related information and services.

“The land reforms are aimed at making the system more transparent. Before buying a land parcel, one can easily check the ownership, status of court cases, bank loans against the property and other crucial details online, which was not the case a few years ago,” the official said.

Also read: Modi govt plans scheme to streamline urban land & property records, pilot project in 8-9 states

When did it start

The government started the digitisation of land records as a pilot project in a few districts in 1988-89. Initially, the process was slow because of the sheer volume of records and the complexity of land record management systems in the country.

While a few states, such as Uttar Pradesh and Karnataka, started the process in early 2000s, others only took it up under the Central government’s NLRMP launched in 2008.

While the 2008 initiative focused on the computerisation of land records and linking them with land registration systems, DILRMP has a much wider scope.

“The scope of work was increased under DILRMP, as it was felt that just digitising land records (textual data) is not enough,” Hukum Singh Meena, a former government officer involved in the implementation of DILRMP, told ThePrint.

“Integrating land title changes with cadastral maps, which show the exact location of land parcels in a village, is essential. For this, digitising cadastral maps and linking them to land records is crucial so that property transactions are accurately reflected in the maps.”

Over the years, the programme has overshot its deadline. And as its latest March 2026 deadline approaches, the progress of some components such as the integration of cadastral maps with land records has been slow because of a host of challenges from the poor quality of records to a web of land disputes.

According to Union Ministry of Rural Development data provided to the Lok Sabha, so far, seven states and Union territories—Goa, Kerala, Tripura, Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Chandigarh, Lakshadweep and Puducherry—have digitised all textual land records maintained in books, while the other states have completed over 95 percent of the process.

However, even though the linking of land records with property registration started way back in 2008, only 18 states and UTs—including Karnataka, Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh and Jharkhand—have been able to completely integrate the data of the two departments.

Similarly, only 23 states and UTs have completed the computerisation of property registration, according to a Parliamentary Standing Committee on Rural Development and Panchayati Raj report tabled in parliament in the winter session.

Cadastral maps have been linked to the Record of Rights in 72 percent of villages in the country, according to the rural development ministry.

Challenges in implementation

The implementation of the land reforms faces significant challenges as land records across the country are plagued by problems.

The northeastern states are particularly difficult because of community ownership of land and the unavailability of land records.

“We are now getting a study done to study the land governance system in these states and recommend measures to digitise the land records,” a senior rural development ministry official said.

The official said the quality of land records and cadastral maps was a serious concern. The maps haven’t been updated for decades in most states and in some cases, are missing altogether.

“A land parcel might have been subdivided between family members, but the cadastral maps don’t reflect it as the family has not applied for mutation to change the ownership in revenue records. This is a problem across the country,” the official added.

To address these issues, several states such as Gujarat and Uttar Pradesh are conducting re-surveys of villages, with some of them using aerial surveys and drones for the task. The Uttar Pradesh government has already begun the process of re-surveying 12,000 villages.

“The re-survey was necessitated as the maps were not in good condition. In some villages, there was a major discrepancy in the cadastral maps, which are nearly a century old, and don’t reflect the actual ground situation,” said the senior Uttar Pradesh revenue department official.

“In some cases, the village maps were overlapping. We are in the process of starting a pilot survey of five villages using drones.”

The Gujarat government is also re-surveying nearly 6,000 villages to address discrepancies. “Our land records are updated. We are just going to each village to verify the land records,” said a senior state revenue department official.

Another big challenge that authorities are grappling with is that in some states like Bihar and Jharkhand land records have not been updated for years, a senior rural development ministry official said.

“While almost all land records have been digitised, the quality of land records is very poor in some states such as Bihar. The change in land ownership is not updated on maps for decades,” the official said.

Meena said that a major hurdle in updating land records was the delay in the mutation of land after sub-division. He said 80-85 percent of land transactions registered in a year are related to the death of a landowner or gifts to family members.

“While people got the registry done, they rarely got the property mutation done due to which the cadastral maps didn’t reflect the change on the ground,” Meena said.

He said that the Centre’s decision to link land records with government scheme benefits, such as Pradhan Mantri Kisan Samman Nidhi (PM-KISAN), has helped boost property mutation.

PM-KISAN provides financial assistance of Rs 6,000 a year to all cultivable landholding farmer families across the country.

However, some states such as Karnataka and Madhya Pradesh have integrated updated cadastral maps with land transactions.

“As the land record digitisation work was completed in early 2000, we have been able to streamline the land record management system. Whenever a land transaction is registered at the sub-registrar’s office, the information is updated in the cadastral maps,” Pommala Sunil Kumar, revenue commissioner with the Karnataka government, told ThePrint.

“If a land parcel is divided between two family members, a new sketch or map of the two new land parcels is automatically created based on the land transaction details.”

But land experts say the digitisation exercise has little meaning until land records are accurate.

“The digitisation exercise has been going on for more than a decade and yet a digital record is not proof of conclusive titling because we don’t know whether it is accurate or not,” said Namita Wahi, a senior fellow and head of Land Rights Initiative at the Centre for Policy Research.

“The priority should be ground-proofing land records and land surveys, and not just digitisation of land records.”

The Centre’s digitisation initiative was aimed at bringing down land-related litigation, which constitutes a large percentage of total court cases in India, but some experts say digitising flawed records could lead to more litigation unless disputes are resolved during the process.

Land and property matters make up about two-thirds of all civil cases in India, according to a study by Daksh, a Bengaluru-based legal advocacy group.

“DILRMP was started with the objective of replacing the presumptive land titling system with a conclusive titling system, which basically places the onus on the government to verify land-related information once the land parcels are registered with it. But this has not been achieved,” said Anirudh Burman, associate research director and fellow at Carnegie India.

“Just digitising existing land records is not enough. It can lead to more litigation if care is not taken to resolve any existing disputes that exist or arise at the time of digitisation.”

Despite the challenges, the government has launched other similar schemes for non-agricultural land.

While DILRMP is aimed at agricultural land and other land parcels, the Centre also launched a new scheme to map residential properties in villages and issue property cards in 2021.

The Survey of Villages and Mapping with Improvised Technology in Village Areas (SVAMITVA) scheme to create land records for inhabited areas is meant to address land-related disputes, help villagers take bank loans against their properties and aid gram panchayats in development planning and collecting property tax.

How the reforms are helping

Despite the challenges, digitising land records has made a difference. Most importantly, it has made accessing land information easier and it has brought down the number of fraudulent deals.

“The digitisation initiative has definitely made access to land records easier for the public. For instance, people can check the details about land ownership, maps, etc online,” said Carnegie India’s Burman. “In many states, people can access a certified copy of their land records from citizen service centres and are no longer at the mercy of the local patwari.”

Amit, head of Malkapur village in Uttar Pradesh’s Jalaun district, said that digitised land records on the state government’s portal have eliminated fraudulent land deals.

“Before buying land, people check online about its ownership status, location, and if there are any pending court cases. Now information about bank loans taken against the property is also available,” said Amit.

“This has helped people make an informed decision and put an end to fraudulent land deals. Earlier, it used to take days to get a certified copy of basic ownership documents from a government office. Now it can be obtained within a day.”

Rural development ministry officials said the ULPIN initiative will resolve land issues as each land parcel in the country will have a unique number.

Some states such as Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh and Gujarat are using the land data for planning development projects.

Deepika Jha, senior consultant at the Indian Institute for Human Settlements (IIHS), said that several states are now using digitised data to plan development projects.

“Development authorities can now look at digitised records in planning infrastructure projects. As the land data is readily available, it is easier for state governments to acquire land,” she said.

(Edited by Sugita Katyal)