Khatu, Sikar: If you are not on Instagram, you are not a god these days among young people. In the pantheon of India’s 33 crore gods and deities, Khatu Shyam is the latest entrant into the universe of reels.

Shruti Saini, 22, from Udaipur parked her black Thar in front of the Toran gate—the entry point to the Khatu Shyam temple nearly 1.5 km away. Standing on the car with her hands in the air, Saini captured the moment on video and posted it online with the song Shyam Sang Preet playing in the background. Her caption read: Tere bina shyam hamara nahi koi re—we have no one but you, Lord.

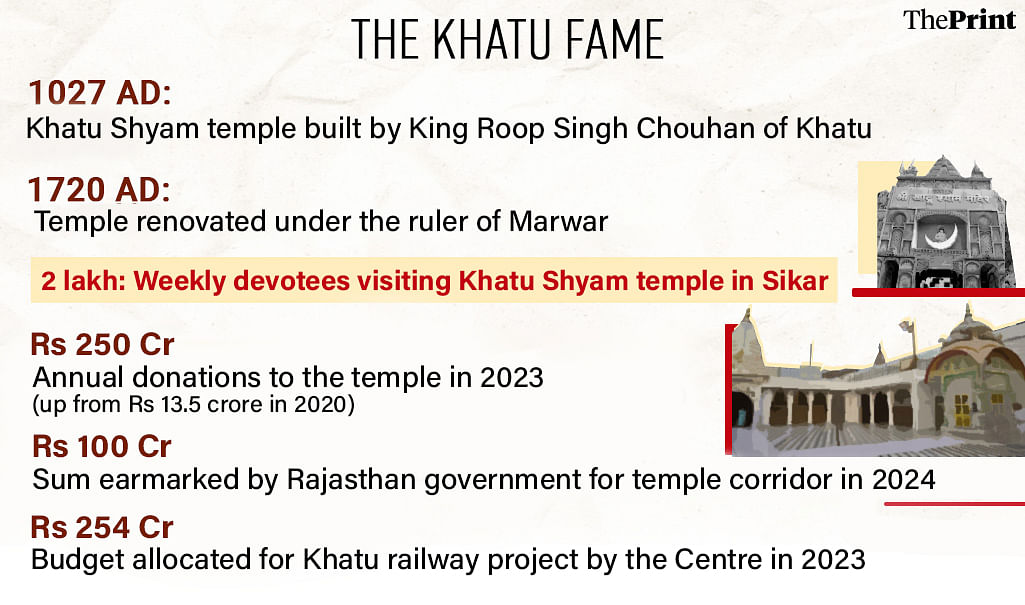

The Toran gate has become a hotspot for selfies and reels, with young devotees travelling from cities like Delhi, Jaipur, Indore, Nashik, and Rampur. Drive, darshan, display, and depart is the pattern for the new generation of devotees. Every week, more than two lakh people turn up, making Khatu Shyam temple one of North India’s fastest-growing religious hubs. Around 50 lakh tourists have visited Khatu Shyam temple during the annual Lakhi mela in March for the past three years, according to the Rajasthan tourism department. The shrine’s annual donations have skyrocketed from Rs 13.5 crore in 2020 to Rs 250 crore in 2023, excluding offerings of gold and silver. President Droupadi Murmu, Vice-President Jagdeep Dhankhar, Bollywood actor Govinda, and former Rajasthan chief minister Ashok Gehlot are some of the prominent people who have visited the shrine.

The Rajasthan government has announced a Rs 100 crore corridor for the temple and a new police station in its latest budget. A new rail line will connect Khatu to the Ringas Junction railway station.

Also known as Barbarika, Khatu Shyam—the son of Ghatotkacha in Hindu epic Mahabharata—has seen his popularity explode over the past few years. From songs to social media to pilgrimage, his growing cult following has transformed the small town of Khatu in Rajasthan’s Sikar into a hub of faith and commerce, quite in sync with Sikar’s emergence as a coaching hub. Khatu is the new Vrindavan for weekend tourists. A pilgrimage to the Khatu Shyam temple also brings spirituality and Digital India together.

“Khatu Shyam has become the new center of faith,” said Mahant Mohandas Singh Chouhan, chief priest and former president of the temple management committee. The craze is increasing, especially among youth. Khatu Shyam is the god of Kaliyug and, as the Kaliyug grows, devotees take refuge under him.”

The devotion extends beyond social media and has given rise to a thriving merchandise industry—car décor souvenirs, stickers, T-shirts adorned with Khatu Shyam’s image, keychains, badges, etc. Cars stickers read “Haare ka sahara Baba Shyam hamara” and “Mai laadla Khatu vaale ka.” Young devotees are resonating big time with these messages. Khatu is their wallpaper, Khatu songs are their ringtones, and they greet with Jai Shree Khatu when answering calls.

Khatu Shyam is now the go-to miracle-making god for anxious Indians from the Hindi belt.

Infra boom, real estate gold rush

Recognising Khatu’s rising prominence, both state and central governments have stepped in with ambitious development plans. The Narendra Modi government announced a Rs 254 crore rail line project connecting Khatu to Ringas Junction railway station.

“A large number of people from all over the world come to visit Khatu temple. Connecting the pilgrimage site to the railway network will provide great relief to the passengers,” Railways Minister Ashwini Vaishnaw told ANI last year.

Khatu now resembles a massive construction site, with dust clouds announcing the arrival of new hotels, guest houses, and residential complexes. This real estate gold rush has driven land prices northwards—from Rs 15,000-20,000 per yard four years ago to Rs 1 lakh today. Real estate investments in Khatu have crossed Rs 1,000 crore in just the last five years, according to district revenue officials. This Navratri witnessed the inauguration of over 100 new hotels and guest houses in Khatu alone, most within 2 km from the temple.

The temple is also part of the Modi government’s Swadesh Darshan scheme, launched in 2015. Under the Krishna Circuit initiative, Khatu Shyam temple, along with Jaipur’s Govind Dev ji temple and Rajsamand Nathdwara, received a budget allocation of Rs 75.80 crore for development.

Dantaramgarh MLA Virendra Singh told ThePrint that between 2018-23, another Rs 200 crore was invested from state government funds for connectivity, power grid, and waste plants.

The latest development came in July when Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan governments signed an MoU in Bhopal to develop a religious circuit connecting Ujjain’s Mahakal to Khatu Shyam, complete with Vande Bharat trains and electric buses.

Prominent businessmen from Kolkata, Delhi, Punjab, and Chhattisgarh have constructed dharamshalas, while upscale establishments like Radhey ki Haveli and Lakhdatar Hotel, run by former temple committee president Pratap Singh Chauhan, serve high-end tourists.

“Currently, [government] projects worth more than Rs 100 crore are in the pipeline,” said Anu Sharma, assistant director of Sikar’s tourism department.

Digital divine: Making of a modern god

BR Chopra brought Khatu Shyam’s legend to the small screen in Mahabharata. Then there was a long period of silence before Khatu took over the internet in recent years.

Naveen Giri started posting shayaris on Instagram in 2020, but his early videos went unnoticed. Everything changed after his first visit to Khatu Shyam in January this year. Since then, he’s shared 185 videos dedicated to the deity, and for his over 14,200 followers, he’s now known as “Shyam ka diwana.”

This digital devotion has created new stars in the bhajan circuit too. Ram, a 34-year-old Bareilly-based bhajan singer, used to specialise in Mata rani ki chowki and Hanuman bhajans across Uttar Pradesh. But he has completely shifted to singing Khatu Shyam bhajans, and receives booking requests from West Bengal, Punjab, Gujarat, Rajasthan, and Assam. Under the banner “Ram Shyam Bandhu,” he and his brother Shyam travel to these states and perform “Ek shaam Shyam ke naam”— evening kirtans that have become community gathering points.

He credited singers, social media, and Instagram reels for popularising the shrine in other parts of the country, adding that four Khatu Shyam temples have come up in Bareilly alone.

The music industry has taken notice as well. Delhi-based Lakhdatar Music and Films has released six Khatu Shyam songs over the past month. T-Series’ bhakti channel has produced dozens of songs dedicated to Khatu Shyam, with Kanhaiya Mittal’s 2020 hit “Gazab mere Khatu wale” accumulating nearly 7 crore views on YouTube while his 2023 song “Main to Khatu Dham ko chala” has been viewed more than 30 lakh times.

Another of Mittal’s viral hits, “Lene Aaja Ringas Ke Mod Par,” even influenced local commerce—the song’s mention of offering three bottles of attar at the shrine has boosted sales at local perfume shops. In the video, Mittal explains an elaborate ritual: “Offer two bottles of attar, then open the third one’s lid while making your wish. Close it immediately after, and if Baba asks what you did, say you’ll offer the third one once your wish is fulfilled.”

Faith, fortune, and the larger purpose

Khatu Shyam, grandson of Bhima and worshipped by various names, received three powerful arrows from Shiva. He sacrificed his head at Krishna’s request, earning the title “sheesh ke daani.” The famous Sikar temple, originally built in 1027 AD by King Roop Singh Chouhan, was renovated in 1720 AD under the Marwar ruler.

But modern India’s latest spiritual success story isn’t devoid of challenges and fault lines.

“After the stampede in 2022 [in which three women devotees died], we had to close 14 backdoors that temple committee members had been using for paid VIP darshans,” said MLA Virendra Singh, who headed the Khatu Shyam panchayat samiti in the early 2000s. He added that the crowds were manageable during those days.

The temple has since acquired additional land for crowd management, including the sprawling Lakhdatar ground just 200 meters away. But Reengus DSP Sanjay Bothra pointed out persistent concerns.

“The biggest problem is that while the entry is spacious, the exit area is very small, which could lead to accidents. The pressure on Khatu is constantly increasing,” the officer said.

Bothra added that Khatu’s growing popularity requires “more than our current staff of 40 police personnel.” During the March fair, a force of 5,000 had to be deployed to manage the crowds. Moreover, the absence of four-lane roads means chances of road accidents are always high.

Yet, for devotees like 22-year-old Aman Panwar, the journey itself is an act of faith.

From his Ghaziabad office, he rang up his 18-year-old brother Himanshu in Shamli and planned a trip to Khatu Shyam temple. Their mother had kept an Akhand Jyoti dedicated to Khatu Shyam for the last two years.

“My mother has never come here. We have purchased a Khatu idol for her,” said Aman, who works at a private firm.

But there’s a bigger purpose in the brothers’ visit to the shrine. “How will India become a Hindu nation unless Hindus visit pilgrimage sites?” the elder one asked.

(Edited by Prashant)

भारत में मंदिर ज्ञान का केंद्र होने चाहिए न की अंधश्रद्धा का।मंदिर लोगो को आत्मज्ञान की तरफ प्रेरित करने चाहिए।ये सब चीजें धर्म के नाम पर की जा रही है जब की ये अहंकार को बढ़ावा देने का कार्य कर रही है।धर्म के नाम पर अधर्म का प्रचार हो रहा है।ये सब चीजें अशिक्षित समाज में ही चल सकती है।नेता लोग इस प्रकार की चीजों को बढ़ावा देते है और पैसा भी खूब देते है।क्योंकि लोगों को जितना मूर्ख रखा जाएगा इन नेताओ का फायदा होगा।अशिक्षित लोगों पर शासन करना आसान होता है।इसीलिए ये नेता लोग शिक्षा को लचर अवस्था में रखते है।धर्मगुरुओं का भी फायदा इसी में है की शिक्षा को लचर रखा जाए।वास्तव में ये लोग अधर्मगुरु है।इतना पैसा लोगों को शिक्षित करने में लगाया जाए। लोगों को वेदांत की शिक्षा दी जाए।लोगों को संत साहित्य,श्रीमदभगवद्गीता,उपनिषद पढ़ाए जाए।वेदांत पढ़ने के बाद ये मूर्खताएं अपनेआप बंद हो जाएगी।