Jhajjar/Delhi: Adarsh didn’t secure enough marks in the NEET examination to embark on an MBBS. As a last resort, he grudgingly chose BVSc — a Bachelor in Veterinary Science. But now, in his fourth year, he’s realised it was a blessing in disguise.

“Everyone dreams of becoming a doctor. But right now, this is the field to be in,” said the fourth-year student at MR Veterinary College in Jhajjar. Once he finishes studying, he plans to open his own private practice in his hometown Chandigarh — a desire fuelled by the slew of shiny new clinics cropping up there.

Until recently, veterinary care was seen as the medical profession’s dowdy step-sister. A drudgery of livestock and animal husbandry; not a career for the aspirational or ambitious. But in the last decade or so, following a boom in pet-parents willing to fork out as much for their canine and feline children as they would for their own offspring, the profession has undergone a drastic makeover. The industry has been retrofitted with cutting-edge ORs, holistic healthcare centres, nutritionists, and luxurious clinics with state-of-the-art testing machinery. Dogs now have pacemakers. Cats have prosthetics. Chemotherapy protocols are in place. And vets are now in vogue.

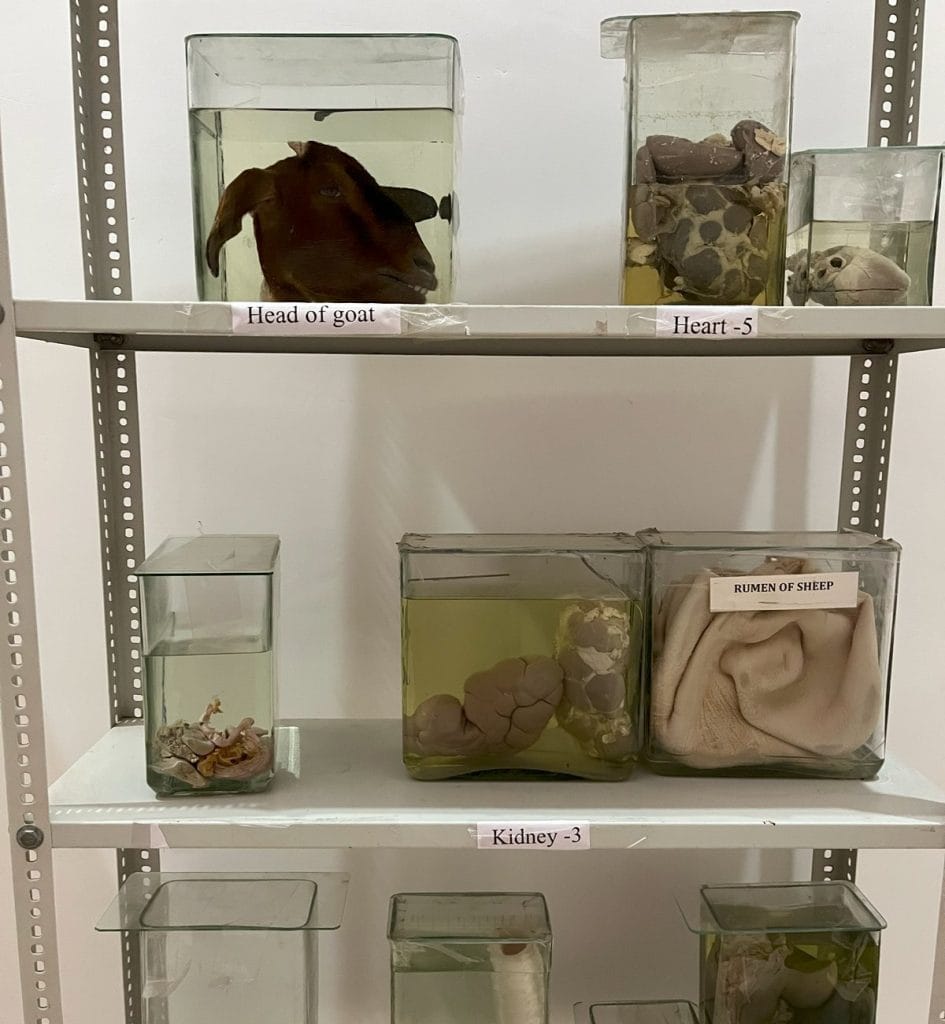

But there’s a catch. The BVSc curriculum, with its fixation on the anatomy of a buffalo, hasn’t received the same upgrade. Classrooms do not mirror these heady changes, where a cattle skeleton, a goat head, and a sheep rumen still hold pride of place.

In an attempt to bridge this gap, vet colleges have upped the ante when it comes to internships. For a year, students are expected to frequent and intern in zoos, pharmaceutical labs, and private clinics.

“There is quite a bit of focus on academics. But our best students want to work in clinics,” said a professor at MR College.

However, Dr Umesh Chandra Sharma, chairman of the Vet Council of India, is convinced that the curriculum, first crafted in 1984, is evergreen.

“What is outdated?” he asked. “It’s not like anatomy and physiology can change. We make certain need-based changes, such as to do with diagnostics and zoonotic diseases. But the topics themselves have remained the same. We’ve always had a holistic curriculum — which focuses on all animals.”

Today’s veterinary graduates are entering a world where pet parents are more informed, demand higher standards of care, and expect advanced diagnostics and treatment options, often mirroring human healthcare

-Dr Kunal Dev Sharma, chief vet surgeon at MaxPetz

There have been some attempts at changes over the years, though. Most recently, in January 2025, the Veterinary Council of India sent a draft to integrate the National Education Policy (NEP) into the syllabus, for which they’re awaiting clearance from the Centre. Before that, amendments were made in 2016, 2008, and 1993. According to those now in practice, the only significant amendment came in 2016, when the internship period was extended. It was a testament to a growing realisation — in order to enter clinical practice, vets need more hands-on training.

Nearly all the students ThePrint spoke to at MR Veterinary College held dreams of the upscale clinics and private practices that pepper tier-1 cities. The tilt also has to do with the simultaneous rise in adoring pet parents.

Nisheetha, a first-year student from Chennai studying in Jhajjar, wants to be a vet specialising in dogs simply because she has a rottweiler and a German shepherd back home.

“I just love my pets, so I want to treat animals like them,” she said matter-of-factly.

In many well-known private clinic chains, starting salaries can go up to Rs 70,000. Due to a ‘continuous education’ approach, there’s also plenty of room to upskill and climb the ladder.

Also Read: The Era of Cats has come to India. They are now the new top dogs

A ‘lucrative’ choice

In a single year, Ansh Arora’s career goals changed entirely — in tandem with the cultural reset that’s turning veterinary care into a coveted profession. He went from aspiring to an MBBS, to a BS in biology, to finally aiming for a BVSc. Now, he sees more promise in it than in human medicine.

“There are very few vets compared to human doctors. Less people choose to enter the field. The demand is high, but the supply doesn’t match up,” said Arora. “Professionally, it becomes far more lucrative.”

Originally from Amritsar and currently a student of biology at Banaras Hindu University, Arora is now building his portfolio to apply for an undergraduate degree in veterinary science at a university in Japan.

According to him, a medical officer’s salary from a top institute in a tier-1 city is around Rs 50,000. Elsewhere, it’s closer to Rs 25,000. But in many well-known private clinic chains, starting salaries can go up to Rs 70,000.

Due to a ‘continuous education’ approach, there’s also plenty of room to upskill and climb the ladder. A vet with about 10 years’ experience can earn between Rs 3 to 5 lakh per month. Salaries have jumped in the past decade or so.

“The salaries are as good as any white-collar job,” Arora declared.

For years, his life revolved around NEET prep. He described being suspended in a state of “emotional and financial turmoil”. It was only after the exam ended that he could finally look beyond it. And that was when he realised the potential that lay outside an MBBS.

Even after graduating, there’s ample scope to grow and specialise through real-world experience.

“Many graduates still lack the clinical confidence or practical experience in complex areas like orthopaedics, neurology, imaging, or advanced soft tissue surgery,” said a senior vet.

Vets have benefited from a new breed of obsessive pet parents. It’s helped drive up their salaries and infused the profession with a different kind of respectability — one that rivals the aura surrounding top doctors.

More prestige, more pressure

Last year, a beagle named Juliet underwent what was claimed to be India’s first non-invasive mitral-valve heart surgery, performed by a team at MaxPetz, a multi-speciality animal hospital in Delhi. The team was led by Dr Bhanu Sharma, a small-animal cardiologist and third-generation vet.

His grandfather started out as an army doctor, eventually handling the Delhi Race Club as well as the Delhi Zoo. Bhanu’s father, Manmohan Sharma, founded Max Vets to give pet-parents a “one-stop shop”. Today, Max Vets has evolved into the MaxPetz chain of animal hospitals and clinics.

“For us, it’s based on interest. We’re working more than ever. Compensation for vets isn’t like how it is for other professions, like architects, for example,” said Bhanu.

We used to feel bad when we treated dogs. ‘Dog doctor’ was used as an insult. No one wanted to spend money on pets back then

-Dr RK Chandolia, dean of MR Veterinary College

MaxPetz is part of a rising fleet of trendy clinics across the country, with plush consultation rooms and well-stocked pharmacies. Their East of Kailash clinic even has a cafe for anxious pet-parents to grab a coffee, and a pet store if they want to further spoil their unwell canines.

Vets have benefited from this new breed of obsessive pet parents. It’s helped drive up their salaries and infused the profession with a different kind of respectability — one that rivals the aura surrounding top doctors.

In order to be taken more seriously, and be more visible to clients, many vets have also become content creators. Noida-based Dr Vipul Chaturvedi, for instance, posts videos of the surgeries he performs, from tail amputations to repairing a bull mastiff’s wound. It adds a layer of legitimacy and allows vets to showcase their skills.

With pet-parents keeping up to date on vet medicine, the demand for specialised care has grown.

“There’s so much scope now for super-speciality in small animals due to how much knowledge pet parents have,” said Bhanu Sharma. They’re also willing to fork out thousands on a bouquet of tests that were once reserved for human beings.

Sought-after vets can command over Rs 1 lakh a month, but the high salaries come with their own pressures. Vets have no choice but to cater to the demands of pet parents.

“Today’s veterinary graduates are entering a world where pet parents are more informed, demand higher standards of care, and expect advanced diagnostics and treatment options, often mirroring human healthcare,” said Dr Kunal Dev Sharma, chief vet surgeon at MaxPetz. A bad rating or review on WhatsApp groups or social media can quickly change the tide from approval to acrimony.

From 2019 to 2024, the number of small-animal pet owners in India rose from 26 million to 32 million, according to a report by the global consultancy firm Redseer. Spending has climbed too, with the pet-care industry being valued at $3.5 billion.

Livestock loophole

Many vets enter the field wanting to treat pets, but their coursework still primarily trains them for livestock. Dr Vipul Chaturvedi, who works at Vetic, a private clinic in Noida, grew up in Mathura, where he had no access to cows, goats, or buffaloes. Instead, he was surrounded by dogs.

“I’m emotionally attached to companion animals, so I enrolled myself in a BVSc. But the curriculum is still more focused on livestock,” he said. But in his last two years of study, he observed a slight shift to pets. This was not due to a change in the curriculum but in the mindset of some professors.

The syllabus, which is based on textbooks by Indian authors, focuses on livestock care and physiology. To fill the gap, his professors began teaching from textbooks by authors from the US and UK, where small-animal care is a top priority.

“They taught us everything from foreign authors. They have good texts on dogs, cats, and exotic animals,” said Chaturvedi. “They tried to enhance our knowledge in these spaces — to make us understand that yes, we have livestock, but if we want to feel like doctors, we need to know companion animal practice.”

One of those books was a manual on small animal surgery by Theresa Fossum, a practising veterinary surgeon in the US. The book was published relatively recently, in 2019.

Most of the standard textbooks by Indian authors — like Primary Veterinary Anatomy by RK Ghosh, Textbook of Veterinary Physiology by Basudeb Bhattacharya, and Textbook of Animal Husbandry by GC Banerjee — were all published decades ago. They feature all animals in theory, but there does appear to be a tilt in favour of livestock.

There are fewer government jobs in Haryana today, and the cattle ratio is high — so we thought of building a vet college. But we have students from 12 states across India

–Sombir Kodaan, managing director, MR College

For instance, GC Banerjee’s book, first published in 1964, has six chapters which look at individual animals. Buffaloes, rabbits, and even yaks find mention but cats and dogs are largely missing. They do appear in some first-year physiology texts, but not as a consistent focus.

Chaturvedi also pointed to a gap in the kinds of treatments that are prioritised.

“Practising livestock is a business. Dairy farmers don’t want to spend on treatment and they see their cattle as liabilities,” he said. “Therefore, veterinary care is focused on management, not treatment.”

When Dr RK Chandolia, now dean of MR Veterinary College, was studying in Hisar, treating cats and dogs was spoken about pejoratively.

“We used to feel bad when we treated dogs. ‘Dog doctor’ was used as an insult. No one wanted to spend money on pets back then,” he said, seated in his on-campus office. “Now everyone wants to practice on small animals.”

Founded in 2021 and targeted at the landowning families around Jhajjar, MR College was initially envisaged as a draw for farmers’ children desperately searching for stable employment, said managing director Sombir Kodaan.

He was wrong.

“There are fewer government jobs in Haryana today, and the cattle ratio is high — so we thought of building a vet college,” added Kodaan. “But we have students from 12 states across India.”

Their first batch will graduate next year. The college also offers two-year diploma courses in essential auxiliary roles, like nursing and lab technician training.

“Even our vet staff [graduates of the diploma programmes] want to work in small-animal private clinics,” said Chandolia. “In our vet college hospital, we barely see any large animals. Farmers don’t want to bring them all the way.”

Learning by doing

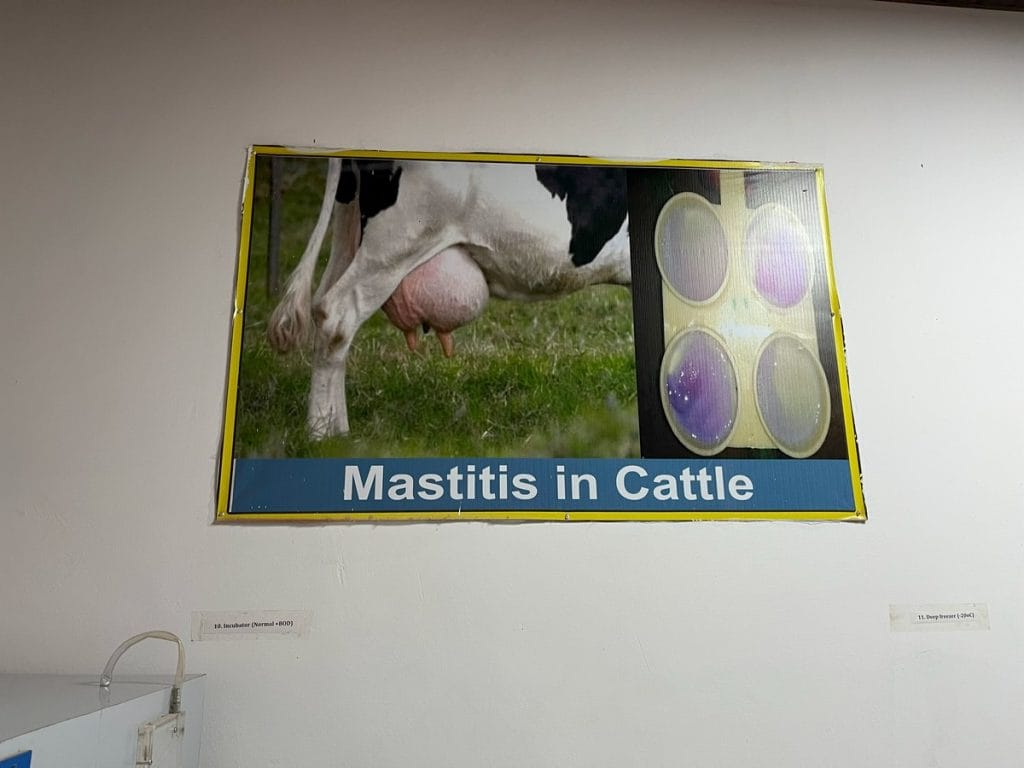

MR College has X-ray machines, surgical instruments for vets-in-training to practice on, and an enclosure stuffed with hens for training purposes. A photograph of an engorged bladder teaches students how to recognise cattle mastitis. With 80 seats and a slew of diploma courses, the college is making the most of the profession’s growing appeal.

The administration is currently in expansion mode, with plans to upgrade infrastructure and introduce more short-term diploma courses. On the horizon are state-of-the-art lecture halls, air-conditioned classrooms, and new offerings in Ayurveda, pet practice, homeopathy, and horse care. Most such courses are designed for vets who have already completed their postgraduate diplomas.

Some colleges are also reimagining how clinical training is delivered.

In Wayanad’s Kerala Veterinary and Animal Sciences University (KVASU), Dr Dinesh PT, associate professor of surgery, has been forced to skip textbooks.

He teaches his students purely through case presentations of the canine and feline patients at the adjacent hospital.

“When it comes to clinical practice, we’ve had to shift. We’ve moved toward the patient. We’re trying to teach students through the hospital,” he said.

In their third year, students begin shadowing practising vets in the hospital for pets once a week.

However, this hasn’t been without its challenges. In their first two years of anatomy and physiology training, students focus only on the bovine body.

“They have to revise the very basis of their training,’ said Dinesh. “They need to study the procedures and the bones once more.”

It does look like a lucrative market given the interest that’s coming from investors. Lots of corporates are entering vet chains. The demand has already risen. And it’s only going to increase from here on

-Dr Bhanu Sharma, MaxPetz

What the Vet Council of India, as well as practising vets advocate for is a Continuing Education (CE) system, by which vets keep upgrading their skills. This has been taken up in a big way by the private sector.

Last month, a conference at Delhi’s India Habitat Centre brought together hundreds of vets from across the country to network with and learn from experts in veterinary neurology and orthopaedics. It was organised by the Asian Foundation of Veterinary Orthopedics and Neurology (AFVON) — founded by a group of vets tapping into the demand for expert orthopaedic and neurological veterinary care.

“Traditional veterinary education, while foundational, often lacks the time and resources to offer deep, hands-on experience in specialised fields. Classroom learning can only go so far in teaching the nuances of a TPLO surgery, performing a neurological workup, or interpreting advanced imaging,” said Dr Kunal Dev Sharma of AFVON.

“Real clinical skill comes through mentorship, hands-on training, and exposure to real cases, which can only happen through immersive programmes outside the classroom.”

One of the sponsors of the event was SAVA Vet, an Indian pharmaceutical company in the animal healthcare space. It is now reaching out to vets in cities across the country to tailor their business around clinical trends and requirements.

“We’re seeing a trend across tier-1, tier-2, and tier-3 cities,” said COO Karthik Ranjan. “So many young vets want to build a clinical practice. We’ve reached out to over 3,000 vets and clinics to tailor our healthcare approach to them.”

Also Read: MCD’s 1st pet crematorium giving dignified send offs to animals—memory garden, priest services

When pets mean profit

At a MaxPetz clinic in East of Kailash, nervous pet-parents roam the halls waiting to see a doctor. A lethargic German shepherd lies sprawled on the floor while his human caretaker waits their turn. A bewildered beagle is rushed in on a stretcher by a haggard nurse. Even something as minor as a kidney function test can set parents back by Rs 800 here.

From 2019 to 2024, the number of small-animal pet owners in India rose from an already hefty 26 million to 32 million, according to a report by the global consultancy firm Redseer. Spending has climbed too, with the pet-care industry being valued at $3.5 billion. According to another estimate, the market could hit $7-7.5 billion by 2028. Brands like Ziggly and Heads Up For Tails are also constantly innovating, releasing new food products and toys on a regular basis.

New sectors are also on the ascendent. Pet wellness, for one, is projected to be the next big frontier, as more pet-parents seek “specialised” care.

“It does look like a lucrative market given the interest that’s coming from investors. Lots of corporates are entering vet chains,” said Bhanu Sharma of MaxPetz. “The demand has already risen. And it’s only going to increase from here on.”

Veterinary clinics have opened in plush neighbourhoods in tier-1 cities, where real estate is typically reserved for the abodes of the wealthy. Tata Trusts opened their Small Animal Hospital in Mumbai’s Mahalaxmi. MaxPetz is planning three new centres in Mumbai, and another in Goa.

What’s powering this boom in high-end vet care is a leap in diagnostic technology. Not long ago, CT scans and MRIs for pets would have been a laughable concept.

“Testing used to be non-existent,” said Dr Sharma.

It’s not just about the bells and whistles. Veterinary practice itself has altered fundamentally.

Dr Anil, a senior vet at MaxPetz who has been working since 1983, once dreamed of becoming a wildlife vet. But the only option then was the forest service. And so, reluctantly, he began working in canine medicine. At one point, he was one of the only vets in Delhi with a postgraduate qualification.

The change since then has been drastic. MaxPetz now has 15 clinics across India. Crown Vet, another chain, has six. Cessna has five. When Dr Anil started out, his only option was working for the Delhi government. Even for those who hope to work with wildlife, there’s a new kind of opportunity through Anant Ambani’s controversial Vantara in Jamnagar, a 3,000-acre “animal rescue centre” with a line-up of exotic animals.

While the profession may be in vogue and investment is mounting, earnest students also spoke about the skill and instinct the work demands.

“Our patients can’t talk. It takes more talent to become a vet. We don’t always know the symptoms we’re working with,” said Adarsh.

But this noble pursuit now comes with real rewards, and there’s no looking back.

“I’m telling you. There’s not a single vet in this country that’s unemployed,” said Dr Chandolia, gazing at the under-construction wing of MR College in Jhajjar.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)