Varanasi: Ever since Ajay Sharma of the Sanatan Raksha Dal ‘found’ a neglected temple in Madanpura, a Muslim-majority area in Varanasi, he has been jumping up and down in joy. The ‘rediscovery’ of what Hindutva leaders are calling Siddheshwar Mahadev Mandir is a major breakthrough in his long-drawn project to uncover lost temples in the city. And he’s just getting started.

“There are 56 more ‘hidden’ temples in Madanpura and adjoining areas alone,” Sharma said with conviction. “Sanatan Raksha Dal and I are working to find them.” Some of these temples, he claimed, are inside Muslim houses. But that doesn’t deter him. If anything, it bolsters his resolve to gain access to them.

“Even if they’re inside Muslim houses, we should be given access. The deity should be prayed to,” he said.

With chandan and vermilion on their foreheads, the Raksha Dal marches through the streets of Muslim-majority areas, unbothered by the wary glares they get. Chanting Har Har Mahadev, they scour Kashi for obscure mandirs.

“Kashi ke kan kan mein Mahadev baste hain (Mahadev is in every speck of Kashi. We’re looking for him). We’re searching for him,” Sharma declared passionately.

Currently, Sharma is negotiating with a Muslim family in Madanpura to allow access to an alleged ancient Kali temple inside their house. His mission has also successfully pushed for the removal of Sai Baba idols from at least 10 temples for reasons of religious purity.

The Sanatan Raksha Dal is an offshoot of the Kendriya Brahmin Mahasabha, a 35-year-old organisation. They claim they’re only interested in finding temples in Varanasi, not starting communal tensions.

“I am not looking for temples to rouse Hindu-Muslim sentiment. We’re not conducting this in any other city,” he said, adding with a grin: “In Kashi, even Muslims chant the name of Mahadev.”

Across North India, temple-hunting outfits with little history or backing have been springing up since the Supreme Court’s 2019 Ayodhya verdict. It is the new front of tinderbox politics. With the aggressive mushrooming of self-styled gau raksha samitis over the past decade in Haryana, others in Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, and Uttar Pradesh took it upon themselves to act as Hindutva’s ground troops to save cows. The temple-hunting outfits are also loosely organised networks working to decentralise the Hindutva agenda, usually with no overt and demonstrable backing from the BJP or RSS. The temple project stretches from Sambhal to Shimla. Their hunts inevitably lead to what they call history’s contested sites—mosques, Muslim homes, or often tense Hindu-Muslim neighbourhoods.

In Varanasi, Hindus and Muslims stay together. When a Hindu locality ends and Muslims begin, I don’t even realise. Just give us our temples. We don’t want to create tension. I’m not pointing an AK-47 at you, I am asking politely

-Ajay Sharma of the Sanatan Raksha Dal

The 2022 Supreme Court judgment, which held that demands for religious site surveys don’t violate the Places of Worship Act, has further emboldened these groups. Across Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Delhi, and Uttar Pradesh, many Hindu activists have embarked on The Great Temple Hunt. It’s a full-time obsession for them. These contestations and demands for temple reclamation are part of a ground-level revisionist project. Even RSS Sarsanghchalak Mohan Bhagwat’s appeals to end these hunts have failed to temper the fervour. And in Varanasi, the spiritual capital of Hinduism, the momentum is only increasing, with ‘activists’ combing the labyrinthine gullies regularly for any signs of a mandap or idol.

While Hindu organisations insist their actions don’t disrupt the city’s peace, Muslim leaders remain vigilant. Their WhatsApp groups are full of forwarded messages about rallies calling for violence against Muslims. The community’s committees are filing complaints against such content with the police, but say nothing has been done. Meanwhile, access to masjids and mazaars is shrinking, and the search for temples is invading Muslim homes.

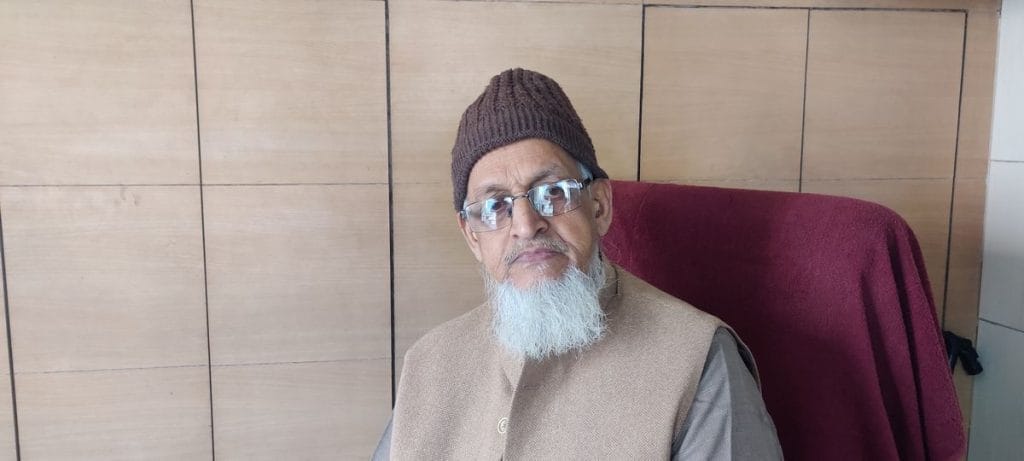

“Maintaining peace is not a joke,” said Abdul Mateen Nomani the imam of the Gyanvapi Masjid. “We know what the consequences of rising communal tensions are. We are trying our best to control our youth and maintain peace, but they’re getting increasingly frustrated.”

The vigilante ‘hero’ of Varanasi

As the mustachioed Sharma strides through Varanasi, temple priests, rickshaw pullers, and roadside vendors greet him with a namaste and smiles, thanking him for his ‘bravado’ and vigilante actions. His many admirers call him ‘Bhaiyaji’.

Sharma doesn’t need a Scorpio to command respect—he travels through the clogged streets of Varanasi on cycle and battery rickshaws, with chandan on his forehead.

In his early 50s, Sharma lives in Varanasi but works as a contractor and sari salesman in neighbouring cities. He says he doesn’t conduct business in Kashi because he considers it too holy for commercial activities. Time is not an issue for him.

Sharma’s organisation, Sanatan Raksha Dal, isn’t a registered political or social outfit. It has no fixed address and exists mostly on Facebook and WhatsApp, where he shares fervent messages about their mission. But it’s made an impact. Among devout Hindus in Varanasi, Sharma is hailed as a hero.

“What he’s doing is daring. Nobody is saving our temples like he is,” said a temple priest, beaming. But his expression changed when he talked about the Muslims in the neighbourhood.

“Muslims will rule the country in some time. Take it in writing from me. You know how I know? Because they’re carpenters, plumbers, sari sellers here,” the priest said, looking at Alamgir Masjid. “We will take this back. Come what may.”

Sharma, however, positions himself as a Sanatani with a higher purpose and distances himself from outright hate.

“We should worship the Muslims who protected the Siddheshwar temple for so long,” he told acquaintances congratulating him for finding the temple in Madanpura. “Look at what the government did—they destroyed so many ancient temples for the Kashi Vishwanath Corridor.”

For Sharma, finding temples is a spiritual mission, not a threat to communal harmony.

“The inhabitants of Kashi have not started conflict; it is those who have come to settle down in Kashi who have started conflict. This place is for dev pooja. You cannot build mosques and pray to ghosts here,” he said.

Yet, he insists he doesn’t target Muslim areas.

Varanasi has been an example of ganga-jamuna tehzeeb. But only philosophically can one say that both communities should understand each other and not let things escalate. I don’t know how to peacefully find and reclaim temples.

-Rana PB Singh, former BHU professor

“In Varanasi, Hindus and Muslims stay together. When a Hindu locality ends and Muslims begin, I don’t even realise. Just give us our temples. We don’t want to create tension. I’m not pointing an AK-47 at you, I am asking politely,” he said. “But if you don’t listen, you’ll see my rudra (awe-evoking) avatar too.”

When Sharma finds a potential temple, he first announces it with a conch. He enters temples dedicated to other deities and investigates if they conceal ancient shivlingams. He claimed he dug up one Shani mandir and discovered it was actually a shivlingam. After ‘finding’ a temple, he looks for a priest, and approaches religious foundations to ensure a steady flow of funds for its upkeep.

Since 2019, he claims that they’ve found close to 50 temples.

“Our volunteers keep track to ensure the temples are well taken care of,” he added.

And the list of temples to be found only keeps growing.

More mandirs-in-masjids on the agenda

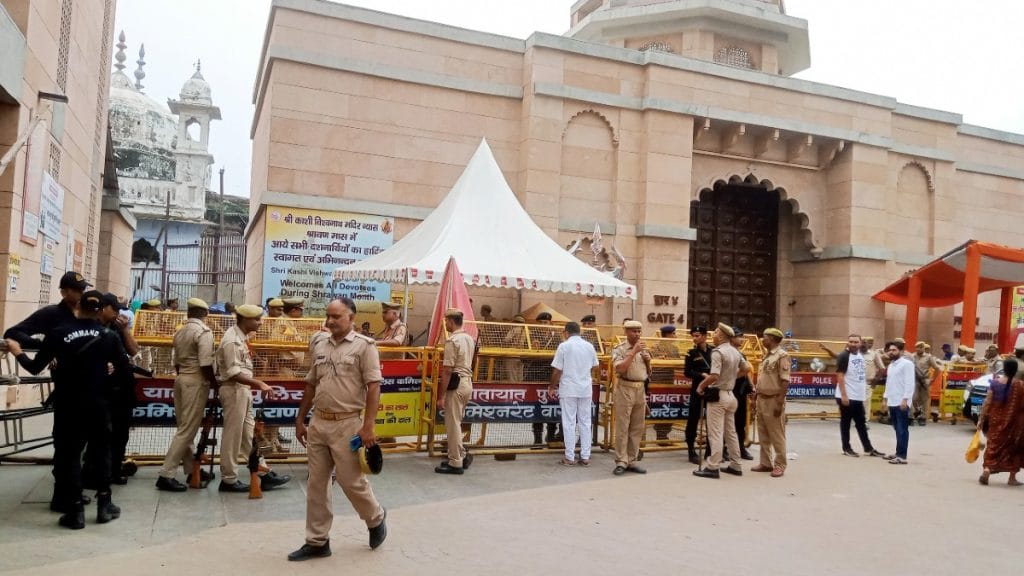

For Hindu groups in Varanasi, Gyanvapi Masjid is just the beginning. A district court allowed worship of a Shiva deity there last January, but it’s just one item off their checklist of potential mandirs in masjids.

Gyanvapi is not the only place widely believed to have been reclaimed by Aurangzeb to build a mosque over a temple. One of the most prominent disputes now centres on the Shri Krittivaseshwar Mahadev Temple, located on the premises of an Aurangzeb-era mosque in the Hartirath area.

“The first temple that was actually attacked by Aurangzeb was Krittivaseshwar Mahadev temple, where he built a mosque. It is the forehead of Shiva, and a pilgrimage to Varanasi is incomplete without visiting this temple,” said Raju Yadav, one of the caretakers of the temple.

At the site, a shivlingam has already been established and prayed to, but Hindus are demanding the construction of a roof to protect the deity.

On behalf of the Shivalingam Virajman, Santosh Singh, a BJP worker, has filed a petition in the Varanasi district court seeking ‘exclusive rights’ over the temple. It also claims that the mosque committee restricts worship at the temple.

Singh says that petitions have also been prepared for surveys of two other contested sites, but they were not filed due to a Supreme Court stay last month on such surveys until further review of the Places of Worship Act.

One of these is the Laat Bhairav Masjid, located next to the Laat Bhairav temple in Jalalipura. The site has seen riots in the past and a court case filed in 2021 asked for the removal of ‘illegal graves’ from here. The other site is the Bind Mahadev temple, where the grand Alamgir mosque now stands.

But these are just the most prominent disputes Hindu organisations are itching to raise in the city. According to Singh’s petition, Hindus believe around 76 temples were destroyed in Varanasi to build mosques in the 15th century. However, every organisation seems to have its own number of temples they are seeking to reclaim.

This is endless. If you go looking for temples, you’ll find one in every nook, corner, and gully of Banaras. How long will this go on? Nobody is stopping anyone from worshipping in temples. But why target Muslims over it?

-SM Yaseen, general secretary of the Anjuman Intezamia Masjid Committee

Rana PB Singh, a retired professor of cultural heritage and geography at Banaras Hindu University, estimates about 25 mosques, idgahs, and other Muslim shrines in Varanasi could be contested as former temple sites. His research identifies 15 historical mosques in the city, alongside more than 1,300 Muslim religious places and over 3,300 Hindu temples.

“Almost all the historical mosques were built using the debris of Hindu temples demolished by Muslim invaders or rulers,” reads a 2010 research paper by Singh, citing invasions from as far back as nearly 1,000 years ago.

“Ahmad Niyaltigin invaded the city in 1033, and demolished the Vishnu temple of Hindus and in 1071 the debris was used to build the Dhai Nim Kangoore mosque, the oldest and most distinct,” the book adds.

A 1995 booklet by the Vishwa Hindu Parishad also claims that eight masjids and mazaars in Kashi are built over Hindu temples. Hindutva groups frequently quote from the ‘Kashi Khand’, a chapter in the Puranas, as evidence of temples in various corners of Varanasi.

Despite supporting the idea of reclaiming temples, Professor Singh advocates finding a middle ground. But even he questions how feasible this is.

“Communal tension is politicised propaganda. The politicians are trying to divide us and rule us. Varanasi has been an example of ganga-jamuna tehzeeb,” he said. “But only philosophically can one say that both communities should understand each other and not let things escalate. I don’t know how to peacefully find and reclaim temples.”

Communal flashpoints and dog whistles

On 29 November, students from Uday Pratap College in Varanasi marched to an ancient mosque on the college premises during Friday namaz, chanting the Hanuman Chalisa and demanding its demolition.

The mosque was unusually crowded that day, according to even Muslim leaders, leading to a heated tussle. The police lodged FIRs and arrested five Muslim youth for commiting acts prejudicial to religious harmony under section 196 (2) of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita. Hindu students were also booked for offences including unlawful assembly, wrongful confinement, and provoking breach of peace. But the FIR complaint doesn’t mention the march towards the masjid.

This incident has put the mazaar, now cordoned off by Uttar Pradesh police, into the limelight. To calm tensions, namaz at the mosque has been stopped indefinitely.

Hindu student leaders argue that if the mosque’s land isn’t Waqf board property, the structure should be removed.

Since then, SM Yaseen, general secretary of the Anjuman Intezamia Masjid Committee, has been poring over land and revenue records to establish the mosque’s history. University authorities claim the structure began taking shape in 1989, but Yaseen presented an 1883 map that clearly shows the mosque’s presence on campus.

“About 22 acres of land were bought by Khwaja Akauk Alwar, according to land records, but we don’t want that land. All we want is to be able to pray at the mosque. But since tensions are high right now, we are not going to pray there,” Yaseen said. “There are some people who are not liking the peace in Varanasi.”

Now our houses will constantly be questioned, maybe even searched for the existence of ‘ancient’ temples. Where does this end?

-Mohd Safi, Madanpura resident

DK Singh, the principal of Uday Pratap College, said the mosque is generally empty, but after Yogi Adityanath declared his intention of upgrading UP College into a university, many Muslims descended upon the university to offer namaz.

“This is a place of education, not a place for prayers,” he added.

But this is just one of many flashpoints threatening peace in Varanasi.

In August 2023, a video of two Sikh traders went viral in Varanasi. It showed them celebrating the demolition of Muslim houses with bulldozers, declaring, “mandir banega rahega” (The temple will be built). They also pledged that Sikhs were ready to embrace “martyrdom for their Hindu brothers”.

Another viral video from February showed a priest abusing Muslims for “reading namaz in the capital of the Hindus” and threatening, “We will end the Muslim bloodline if namaz is read at Gyanvapi”.

In August 2024, a rally was taken out in the Sigra area, where the bloodthirsty chant of “jab mulle kaate jayenge, Ram naam chillayenge” (When Muslims are cut down, they’ll shout Ram’s name) was yelled repeatedly.

Yaseen wrote complaint letters to the police commissionerate about the two social media videos and asked for FIRs to be lodged, but no such action was taken.

And now the ‘discovery’ of the Siddheshwar Mahadev temple in a Muslim locality has only exacerbated the community’s fears.

“This is endless. If you go looking for temples, you’ll find one in every nook, corner, and gully of Banaras,” Yaseen said. “How long will this go on? Nobody is stopping anyone from worshipping in temples. But why target Muslims over it?”

Also Read: Ghaziabad’s Pinky Chaudhary quit Bajrang Dal to ‘save Hinduism’. It wasn’t aggressive enough

Temple unlocked, fears unleashed

Now that the initial jubilation has died down, the newly ‘discovered’ 250-year-old temple in Madanpura cuts a forlorn figure. The footfall to the temple has dried up rather than grown due to the controversy surrounding it. Fewer people now come to the nearby market.

Siddheshwar Mahadev shot into the national spotlight just a day after another temple was ‘discovered’ near the Shahi Jama Masjid in UP’s Sambhal on 14 December. Sharma said his Facebook post about the temple structure in Madanpura began to go viral shortly after. On 18 December, Sharma and members of the Sanatan Raksha Dal arrived at the site, blew a conch, and demanded the temple locks be opened. This caused tension in the residential area, and the police intervened.

The ‘discovery’ set off a social media frenzy, with allegations of Muslim ‘encroachment’ over a Hindu temple dominating public debate. Reports also widely claimed that the temple had been uncovered during an anti-encroachment drive.

However, residents of Madanpura dismiss the notion that it was ever ‘hidden.’

“People say the temple was found, as if it was hidden. While it is right in the middle of the market, where Hindus visit very often to buy saris,” a Muslim shopkeeper in Madanpura said.

The family living next to the temple denies ever harming the structure in any way.

“We always did repairs of the structure from the outside. We never went inside, and never stopped anyone from worshipping here,” said Mohd Zaki, one of the residents of the house.

Muslims in the area point to other temples in the gully that are also attached to homes. Prayers continue uninterrupted here, they point out, to show they have no issue with Hindu places of worship. But as of now, they are afraid normalcy to their lives will never return.

“Now our houses will constantly be questioned, maybe even searched for the existence of ‘ancient’ temples. Where does this end?” asked Mohd Safi, a resident.

In the meantime, Sharma is busy writing letters to district officials, demanding prayers be allowed at the temple with immediate effect. “Not just this temple, I’ll find all 56 and ensure people worship the deities, even if they’re hidden inside houses.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

Ms. Shubhangi Misra just cannot take criticism. Hence, not a single comment on this article was published by The Print.

Pathetic journalism from Shubhangi Misra. Does Shekhar Gupta have no supervisory role at The Print? How come he allowed such a half-baked and blatantly partial and biased article to be published on this platform?

Or is this an example of his much-vaunted “un-hyphenated journalism”?

Is this article an example of “un-hyphenated journalism” as claimed by Shekhar Gupta?

Is this what Mr. Gupta refers to as “objective journalism”?

Such a shame!

May Mahadev bless and protect these people who are desperately seeking to preserve their heritage and culture.